Drifting Oligochaete Worm

By Fox Statler (Mr. Sowbug), Salem, AR

Could Every "San Juan Worm" Ever Been Tied Be Wrong?

I bet you are all saying, "This guy has lost it."

Am I crazy? Nope. In June I had a guide trip with

Ray Askins from Mansfield, Ohio and his son Mark

from Kansas City. At least twice a year for the

past twenty years I have guided Ray and Mark. Ray

is 82 years old, a good fisherman, a wonderful person,

and a great companion. Mark is an intelligent, gentle

man with a clean sense of humor. People like these two

make guiding enjoyable. Because of Ray's age, I wade

fish him only in gravel that is as flat as a parking

lot. I admire his courage. Every year he insists on

wading one day or at least part of a day.

On this day we were fishing at the Norfork Dam pool

on the North Fork of the White River in north central

Arkansas. The water seemed to be colder than other years

and the gravel was caked over with an inch thick crust

of olive-brown, dead algae. The fishing was slow, but

the fish were good size. The fly had to be dragging

on this yucky algae in order to get a strike.

We were using a dark gray "Planarian" imitation dropped

under a "White River Dead Drifter Sowbug" and catching

fish 14-17 inches long. Ray and Mark were enjoying

themselves and I did not want to interrupt their visit.

I was busying myself with the awful algae on the gravel.

I had backtracked our trail into the water and noticed

that the fish were feeding wherever the algae crust was

broken by our boot tracks. The water was about 18 inches

deep and a large flake of the algae had floated downstream

from where it had been disturbed. I placed my boot next

to it. Then I yanked my foot up quickly trying to create

an upwards current that would carry the algae chunk near

the surface where I could capture it without getting too

wet. The algae chunk disintegrated from the sudden current,

and a pink object caught my eye. Quickly I thrust my hand

into the water below the object and let it descend into

the palm of my hand. Slowly raising it out of the water,

I realized I had captured a worm as it began to crawl about.

I dropped it back into the water and something very strange

happened. I caught the worm again hurriedly. I dropped it

again. I must have done this 10 or 15 times, each time the

same thing happened. Letting that worm go, I quickly found

another one to test. I dropped it and the same strange

thing happened again.

Ray and Mark decided to quit early. After the goodbyes

and the "I'll see ya in the fall," I returned to the

water to investigate my worms. I caught about 50 worms

in the next two hours and believe it or not, they all

did the same thing. I borrowed a worm from a bait

fisherman but his worm acted differently than the

worms in the river. I had never heard another fisherman

mention what I had seen. I headed home to research my

worms on the internet. I knew I had discovered something

that could change worm fishing forever.

Once home I brought the computer up, hit the favorites

for "www.google.com" and typed in "aquatic worms." I read

and read and read but nowhere was there a mention of what

I had seen. I read about what lives in tailrace waters of

Arkansas. I found there are over a hundred specie of aquatic

worms. Some even have eyes. The worms that live in our lakes

and rivers are called "Oligochaete" (ol-i-go-ket). For some

reason, I like the ring of that word. I learned that these

worms live in rivers that are considered to be "Organically

Polluted" waters. My search taught me that biologist know

this because of the aquatic insects and worms that are found

in my rivers. I read on, I discovered that the problem of

organic pollution will increase as the lakes above our rivers

become older and more stratified. And finally, I learned that

as the diversity of insects and worms disappear in our rivers

the more serious the organic pollution becomes.

I live in Arkansas by choice. The lakes, streams, and

rivers in this state are my joy. I never cared to travel

west and fish such rivers as the Yellowstone, the Madison,

etc. Why? As for fish, they don't raise them bigger than

they grow in Arkansas. Dry fly fishing is not my passion.

Nymphing and streamer fishing is the ultimate for me

personally. Somehow I got a lot of Boston Mountains'

water in my blood, probably by osmosis. It makes me

angrier to have a cow take a dump in my streams than

any insult you could give me. I would rather save a

half mile of any stream in the Ozarks than all the

rivers in Montana. You bet I'm selfish! I hope you

are too! We should all take care of what is ours first

before we try to save the rest of the world.

There has been a lot of talk about what some people

consider to be signs of ecological disaster in our

Arkansas rivers. Truthfully, it is just "so-much-poop,"

"bull-hockey," garbage. The bugs in our rivers are the

best indicators of the changes that are taking place,

as they are in yours. The more one sided and less

diverse the selection of bugs becomes the more problems

we all will have. Have you looked in your favorite river

lately?

After guiding on the White River and North Fork of

the White River for over twenty years, here are some

of my observations: Several islands and gravel bars

in the river are gone or have moved down stream. This

is normal. The banks of the rivers are still deteriorating.

This will not stop until the Corp of Engineers change

their method of running the river. This may never happen.

Until then I am thankful for the landowners who preserve

the banks with limestone rocks. Coon-tail Moss is still

growing in the silted areas of the rivers. It is a remnant

from when the rivers had warmer water. Sowbugs may be on

the decline in the North Fork but scuds, caddis, craneflies

and mayflies are on the increase. This is good. The same

is true of the White River. In the White River, the scuds

have changed color from a red-brown to dark-olive over

the years because of the increased algae that is present

on the river gravel. The White River has changed from a

yellow and brown gravel bottom river to a light and dark

olive bottom. The fish are generally smaller and presently

there are fewer throughout the White River system below

Bull Shoals Dam. The hatchery at Spring River is being

renovated which adds to the present problem. As for smaller

fish, we need better regulations and to give more power and

authority to our AG&FC Officers. In my opinion, we need to

replace a couple of State Representatives, a Judge in this

area, and one or more commissioners of the AG&FC that don't

believe in catch-n-release. Plainly said, plainly the truth.

We need to be more concerned about what is happening to the

water in our upstream lakes. Pollution here translates into

long term problems in our rivers. The people who live on the

banks of our streams and lakes are the main polluters of our

waters. We need to be continually watchful of them. Every

septic tank adds to the pollution problem. We need to become

more "Progressive" in our thinking instead of the "Reactionaries"

we are now.

Back to my Oligochaete Worms. The adult worms in my river

are 3 to 4 inches long and about an eighth of an inch in

diameter. They are shell pink to cerise on the main

portion of their bodies and have a bright red tint on

the ends due to the collection of blood vessels at the

hair-fiber breathing apparatus. A mud line can be seen

under their skin which changes color depending upon the

type of dirt that they are found in. In most cases the

mud color is a dark gray.

I once watched a program on the behavior of worms

on the Discovery Channel. Ancient worms searched

for food randomly, while the more advanced modern-day

worms search methodically. What is the difference

between an Oligochaete worm and an Earthworm?

Oligochaete drowns in air and an Earthworm drowns

in water. Do they exhibit different behaviors in

the same situation? Yes. When you drop an Earthworm

in water it tries to wiggle free of it. Oligochaete

do not. Instead they coil up like a corkscrew with

a short tail and fall to the bottom quickly, then

disappear into the gravel, mud, or debris on the

bottom. This is what I saw. As long as the Oligochaete

Worm is falling or moving in the water column it is

coiled up tight like a spring or corkscrew with a short

tail. Once it stops moving it quickly crawls away. So

not all of the San Juan Worms are tied wrong, just the

ones you fish in fast water. I don't know if the aquatic

worms in all rivers and lakes exhibit this behavior.

But I am lead to believe that if a particular specie

of worm is within a river system, then it can be found

throughout that entire system. This would mean that the

Oligochaete Worm I observed would be throughout the

Mississippi Drainage system.

Strangely without knowing it, our fathers taught us

a valuable fishing lesson. Hook the worm on the hook

several times. We did this to keep from loosing the

worm so quickly. We didn't know that it was a better

imitation of an Oligochaete Worm. Thanks Dad for

taking me fishin'.

What I observed has brought about several changes

in tying the worms I fish on the White River system.

Now instead of tying a single colored worm, I always

color the ends with red permanent marker pen. Because

of the shape that the Oligochaete worm assumes when

not on the bottom, it is easy to add weight. Different

amounts of weight can be added to get the worm near

the bottom in fast water. When fishing high water

caused by a heavy generation cycle of the dams, I

use a worm with as many as ten wraps of .035 lead

wire. This is enough weight to replace the "BB"

split shot which was placed about eighteen inches

above the worm I had been using. During low water

periods, I generally prefer patterns with six to

eight wraps of .020 lead wire. However, I do carry

a few worms that have no weight in them. I use these

when dropping a worm under another weighted fly.

The realization of what an aquatic worm caught in

the current looks like has also brought about an

understanding of why some controversial patterns

work. The first of these is a large egg pattern

that is successful when no spawning is occurring

in the river. Fluorescent shell pink eggs with a

red spot in them are a favorite among egg patterns.

Pink jigs are another such pattern. What do they

really imitate? Probably a flesh pattern. However

the flesh of most fish is a whitish-pink. The flesh

of trout may be shell pink in color, but there are

never enough decomposing or shredded trout in the

our rivers to warrant the productive abilities of

pink jigs. Another question is also answered because

of behavior of the Oligochaete worm. Browns are rarely

caught in the heavy generation cycles on worms. Browns

being as particular as they are would have no problem

recognizing that a San Juan Worm is not in its environment

during these periods. The San Juan worm is a good imitation

of an earthworm that has been washed into the river by

rain and bank deterioration. I have often noticed how

productive a San Juan is after a heavy rain. But when

the weather is dry, San Juan's are a moderate producers.

Here is my imitation of an Oligochaete Worm, they are

simple and versatile. ~ Fox

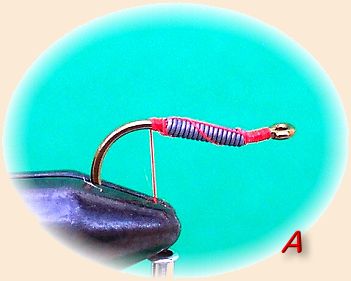

Materials List Drifting Oligochaete Worm:

Hook: 2170 series Daiichi Bent Shank hook, sizes #12 - #4.

Thread: Red or Fluorescent Red 8/0 Uni-Thread.

Lead Wire: None to 8 -10 wraps of .035 lead wire

depending upon the amount of lead wire need to get the

worm down into the current well.

Body: Ultra Chenille, small to medium, length 3 to 4 inches.

In colors of Fluorescent Shell Pink, Fluorescent Pink, Fluorescent

Red, Shrimp Pink and Wine.

Marker: Red Prismacolor Pen or Red Permanent Marker Pen.

Instructions - Drifting Oligochaete Worm:

Step #1: Place the hook in the vise. Wrap the

amount and size of lead desired in the middle

of the shank of the hook. Start the thread at

the eye of the hook. Wrapping toward the bend

of the hook, tie down the lead (if used). End

up at the beginning of the hook bend. Cover the

thread wrappings with a light coat of glue.

Step #2: Cut the desired length of Ultra Chenille

for the body. Color the last 1/4 Inch of each end

lightly with a red pen. Tie in the Ultra Chenille

at the beginning of the hook bend leaving a 1/2 to

3/4 inch tail. Wrap the thread forward to the middle

of the lead. Loosely wrap the Ultra Chenille to this

point and tie down with two wraps of thread. To make

the wraps uniform, use a small knitting needle or

toothpick.

Step #3: Wrap the thread to the eye of the hook.

Loosely wrap the remainder of the Ultra Chenille

to the eye of the hook. Tie down the Ultra Chenille.

Whip finish and glue the threads of the head.

This pattern is a great imitation of an Oligochaete

Worm caught in the current. Only one thing is missing;

the mud line. If Ultra Chenille was constructed with

iron-gray or black threads in the center, this pattern

would be a perfect representation. I have discovered

that Oligochaete Worms work extremely well in fast

water for trout, smallmouth, and other specie of fish.

I generally start the morning using a fluorescent red

worm. Change to the fluorescent pink by mid morning.

Fluorescent shell pink or shrimp pink for midday.

Follow these colors in reverse for the afternoon

and evening. The wine colored worm works well on

very cloudy days from mid morning to mid afternoon.

The reason the colors of the worms that work well

changes during the day is due to the angle of the

sun, cloud cover, and the color of light that is

penetrating the water. This is also true of San

Juan Worms and Jigs.

~ Fox

About Fox:

Fox is a retired educator, fly designer for Spirit River, guide

and author of Fishing What They See,

available on his website,

www.fishinwhattheysee.com.

|