March Brown Spundun

Dry Flies with Life Vests

By Art Scheck

The biggest advantage of tying a no-hackle dry fly

is not paying for rooster feathers that cost considerably

more per ounce than gold. For many tiers, that benefit

outweighs the drawbacks of some no-hackle designs:

marginal floatation, poor durability, difficulty of

tying. When one-third of a specially bred chicken can

cost more than a good fly line, fly tiers look for

alternatives to fowl.

That's why I've included this chapter. [See credits

at bottom of this article.] The flies

we're going to examine don't require hackle feathers,

but they avoid the drawbacks of many no-hackle constructions.

They float well, they hold up as well as most dry flies

and better than some, and they're easily tied with cheap

materials. I call them Spunduns, a reference to the

spun deer hair that forms their wings and thoraxes.

In profile, a Spundun resembles the Comparadun style

invented by Al Caucci. But the two flies are built in

entirely different ways. On a Comparadun, the butts of

the wing hair are bound down by thread, adding weight

and bulk to the fly. The butt ends of a Spundun's deer-hair

wing surround the front of the body to become a plump,

buoyant thorax; they function as a miniature flotation

vest. When treated with a good floatant or waterproofing

agent, Spundums float very well and for a very long time.

How long? How does five weeks grab you? That's how long

a test batch of Spunduns remained afloat. Actually, they

never really sank. I finally threw the flies out because

after five weeks in a container of water, they began to

look like a science experiment gone horribly wrong.

A Spundun has only three components: tails, body, and

deer hair. It's a simple construction that progresses from

one end of the hook to the other. Spunduns can be tied to

represent all but the smallest mayflies, and they eliminate

the expense of dry-fly hackle.

The Parts

As they do on most dry flies, stiff, shiny hackle fibers

make good tails on Spunduns. Suitable fibers can come

from large neck hackles (including those from cheap, imported

rooster capes) and strung saddle feathers that don't have

too much web. Other materials also work: calf tail,

woodchuck guard hairs, moose mane, and, on small patterns,

synthetic fibers such as Microfibbetts.

Dubbing is the most versatile body material, though Spunduns

can also have bodies made with peacock herl or stripped quills.

Any of the dubbing suitable for other dry flies will work on a

Spundun. On smaller pattersn, the fine synthetic dubbing are

easier to use. Natural furs should have the guard hairs

removed.

Use fine, soft deer hair for the wing and thorax. Such material

is usually sold as "coastal deer" or Comparadun hair. The tips

of longer hair might work, but they're sometimes too hard to

flare and spin when you tighten the thread. About the only way

to find out is to try hair from various patches of hide.

Most deer hair has dark tips, though the length of the dark

band varies considerably. Try to use hair with the shortest

possible dark area at the tips. After stacking a bundle of

hair, you can trim a little bit off the tips to shorten

the dark band.

Flymaster 6/0, size 8/0 Uni-Thread, and such like threads are

strong enough for tying small Spunduns, which require tiny

bundles of deer hair. On size 14 and larger flies, I

use size 3/0 Monocord or sizr 6/0 Uni-Thread for both their

greater strength and the speed at which they let me build up

the head. The latter item is important, because a Spundun's

head is what props up the deer-hair wing.

Tying a March Brown Spundun

There's only one tying tip for these flies: Leave the front

quarter of the hook shank naked until it's time to add the

deer hair. As long as you do that, you will have no trouble

tying a Spundun.

For our sample fly, let's tie an Eastern March Brown version

of the Spundun. This is a fairly large mayfly, which means

that our imitation has enough room for me to show you another

method of making divided tails. Here's the recipe.

Materials List March Brown Spundun:

Hook: Standard dry fly, size 12.

Thread: Tan 3/0 Monocord.

Tails: Brown or ginger hackle fibers divided by a tiny

ball of dubbing.

Body: Yellowish brown dubbing. The dubbing shown in

the photos is a blend of brown and yellow fur. These mayflies

vary in color from place to place; some are more brown, others

more yellow. If you want to duplicate the color of your local

bugs, you'll have to catch some and study them. Generally, though,

you can get by with a blend of two parts of medium brown material

and one part yellow. On a fly this big, rabbit fur works fine.

Wing and Thorax: Natural deer hair.

Instructions - March Brown Spundun:

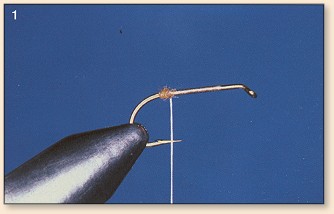

1. Attach the thread one-fourth of the shank length behind

the hook eye; be sure to leave the first quarter of shank

bare. Wrap back to the end of the shank. Twist a tiny

bit of dubbing onto the thread and wrap a small ball of

dubbing at the start of the hook bend.

2. Tie in a few hackle fibers on the near side

of the shank, then tie another few on the far side.

The tiny ball of dubbing keeps the two bunches of

fibers separated, giving the fly forked tails. You

can use this trick on most mayfly patterns.

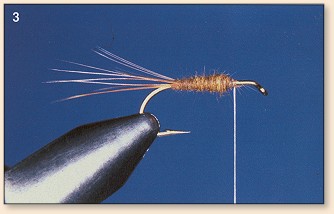

3. Dub the body, stopping at the one-quarter mark

of the hook shank. Build the body with a slight

taper.

4. Clean a small bundle of fine deer hair. Stack the

hair to align the tips. When you separate the halves

of the stacker, do it so that the tips of the hair are

pointing forward, as shown.

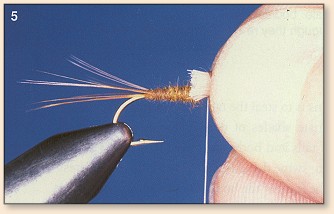

5. Measure the length of the wing. The thread should

interest the hair about one hook-shank length from the

tips. Hold the hair with your fingertips even with the

tie-in spot. Cut the butts straight across about 1/16

inch from your fingertips. Hold the hair atop the hook

and pass the thread bobbin over the hair twice, making two

soft wraps around the butts.

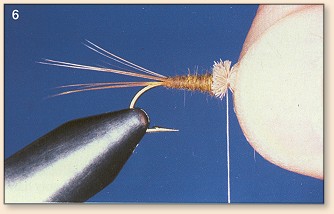

6. Slowly tighten the wraps by pulling the bobbin

straight down. The hair will begin to flare. As the

butts of hair stand up like those in the photo [above]

release your grip on the hair. Tighten the thread all

the way, spinning the hair around the hook. Make another

two or three wraps of thread in the same spot to secure

the hair. The process is like spinning the head of a

Muddler or Fathead Caddis, except that the hair is

backward.

7. You can fold the hair back with your fingers,

but a small tube makes the job easier. This is a

piece of plastic tubing. Slide the tube over the

hook eye and push it against the base of your hair.

Once the hair is roughly perpendicular to the hook,

you can fold it back with your fingertips.

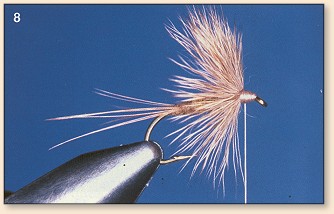

8. Gather all the hair and fold it toward the rear.

Wrap a head against the front of the hair. Be sure

to make a number of wraps right against the base of

the hair; the fly's head is all that keeps the hair

elevated.

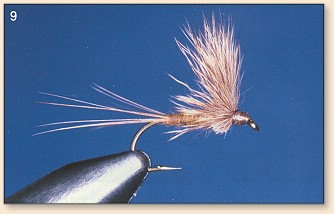

9. Whip-finish the thread. Trim the hair under the

hook to the same length as the butts. Cement the head

and apply a tiny bead of cement to the base of the

wing.

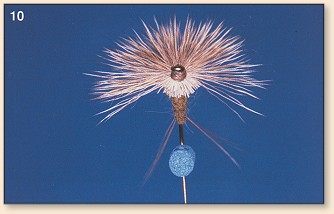

10. The butts and the trimmed hairs form a buoyant

thorax. If the pale color of the thorax bothers you,

tint the hair with a permanent marker. Most mayflies,

however, have pale bodies. This shot also shows the

forked tails, though they're out of the cameras's depth

of field.

Options and Variations

The easiest way to cook up Spundun patterns is to

steal the tails and bodies of established patterns

and combine them with appropriate shades of deer hair.

For a Light Cahill Spundun, use the standard pattern's

cream tails and body, and make the wing with pale tan

deer hair. To tie a Hendrickson Spundun, swipe the

tails and body of the classic dressing and spin a clump

of dyed-gray hair on the front of the hook. For the wing

of an Adams Spundun, use deer hair with pronounced dark

bars.

The easiest way to cook up Spundun patterns is to

steal the tails and bodies of established patterns

and combine them with appropriate shades of deer hair.

For a Light Cahill Spundun, use the standard pattern's

cream tails and body, and make the wing with pale tan

deer hair. To tie a Hendrickson Spundun, swipe the

tails and body of the classic dressing and spin a clump

of dyed-gray hair on the front of the hook. For the wing

of an Adams Spundun, use deer hair with pronounced dark

bars.

You can also study real mayflies or photos to

determine the best colors of deer hair to use for

wings. On most patterns, though, grayish tan

or dyed-gray hair works well enough to fool fish.

This construction does not lend itself to tying

imitations of the smallest mayflies. I can manage

Spunduns on standard size 16 dry-fly hooks; a

short-shank hook lets me produce a fly roughly

equivalent to one tied on a size 18 standard hook.

That still leaves out some little bugs such as Tricos

and the smaller olive mayflies. I can live with

that. A cheap, simple, buoyant construction that

I can use for better than 90 percent of mayfly

hatches strikes me as a pretty good deal. . . ~ Art Scheck

Credits: From Tying Better Flies,

by Art Scheck, published by The Countryman Press.

We appreciate use permission.

|