Aftershaft Leech

By Philip Rowley

About 9 years ago I was fishing Whitetail Lake in southeastern

British Columbia. Whitetail Lake has a reputation for

large trout although its gin-clear waters and scenic

beauty are reason enough to visit. Leech patterns

were proving to be successful specially in the early

evening but I was not satisfied with their performance.

One evening I was fortunate to hook a good fish. Just

prior to releasing him, I pumped his stomach and found

he had been feeding on a number of 3-inch leeches.

Looking at the leeches in the palm of my hand, it was

clear how slender they were, about the diameter of a

pipe cleaner. Reviewing my own leech patterns confirmed

my suspicions, I needed a new slim life-like pattern.

The late Gene Armstrong from Kaufmann's Bellevue, Washington

location developed a number of successful lake patterns

using filoplume or aftershaft feathers as his primary

ingredient. Spurred on my Gene's designs I created my

own version of his Filoplume Leech. The next evening,

armed with a handful of these feather duster patterns,

I tried my luck. Using a dry line and a weighted pattern

to probe the shallows, my variation was an outstanding

success. A number of Whitetail Lake's larger inhabitants

towed me around the lake on that trip. I will always

remember their searing runs. The aftershaft made a

realistic body and, coupled with a long marabou tail

and pheasant rump hackle, mimicked the natural leeches

perfectly. I had found my ideal leech pattern both

slender and animated.

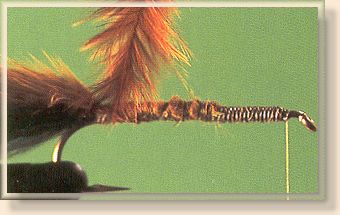

Over the years I have added additional leech patterns to

my fly box, yet the Aftershaft Leech has remained a

permanent resident. When some of my louder leech patterns

don't seem to be working, the somber nature of the aftershaft

leech often does the trick . . .Aftershaft is the secondary

feather found on most game birds. The best source for this

material is ring-necked pheasant. Aftershaft comes in a

variety of colors. I like aftershaft feathers so much for

stillwater flies that I often joke that I should just throw

the balance of the pheasant away. The only drawback to

aftershaft feathers is their strength. Aftershaft feathers

are brittle and difficult to wind onto the hook like other

feathers. Employ a dubbing loop to control this material.

Prepare the feather by trimming the butt and plucking the

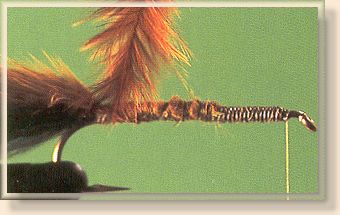

tip. This practice makes the feather manageable. . . Using

aftershaft feathers for the entire body allows for the

creation of a mottled leech pattern. My favorite color

combinations are black and burgundy, black and purple

and dark and light olive. This latter color combination

gives a realistic camouflage look and I have nicknamed

this version the "Camo Leech." All of these combinations

have worked well and pattern selection is often just a

matter of which one I grab first. To further accent

the natural motion of the aftershaft feather, I added

a long marabou tail and a pheasant rump hackle tied

Carey style. These soft-flowing materials work in

unison to create a fly that breathes and pulses in

the water. Be prepared for takes on the drop when

fishing this pattern. Weighting the front portion

of the fly further animates this fly.

The Aftershaft Leech has been a wonderful pattern over

the years and continues to perform despite some of the

rookie leech patterns that now grace my fly box. I

feature my Aftershaft Leech whenever I teach a course

or provide a fly-tying demonstration.

Materials: Aftershaft Leech

Hook: Tiemco 5263, #6 - #10 (weighted).

Thread: Color to match body.

Tail: Marabou.

Body: Aftershaft feathers (mix colors to create

a mottled look).

Hackle: Pheasant rump (color to match body).

Tying Steps:

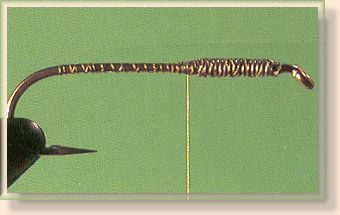

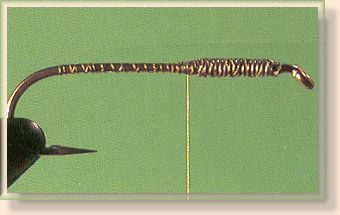

1. Place hook into vise and cover the front 1/3 of the hook shank with

lead wire substitute. Attach the tying thread and cover the wire to lock

it firmly in place. Leave the tying thread hanging at the rear of the lead

wire.

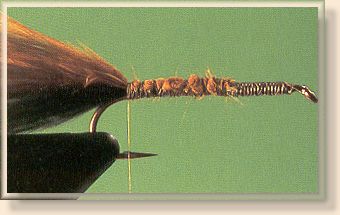

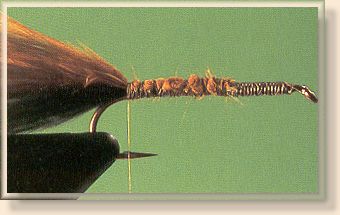

2. Strip a clump of marabou fibers from a marabou feathers. Tie in the marabou

at the rear of the lead wire. The finished tail should be about shank length.

Try mixing various colors of marabou to create a mottled effect.

3. Pull down a 4- to 5 inch length of tying thread. Place a thin

coating of dubbing wax onto the tying thread. Place the prepared aftershaft

feathers onto the tying thread to the stem of the feather lies directly on

top of the tying thread. Lay the feathers tip to butt along the tying thread.

A size-8 fly takes about 5 aftershaft feathers.

4. Bring the tying thread back up to the hook shank to form a dubbing

loop. Clost the loop at the hook shank and spin the dubbing loop tight

reinforcing the aftershaft feathers. Spin the loop until the stems of

the feathers are no longer visible and the fibers radiate out perpendicular

to the dubbing loop.

5. Wind the aftershaft dubbing loop forward to the eye to form the body.

Tie off and remove the excess aftershaft dubbing loop.

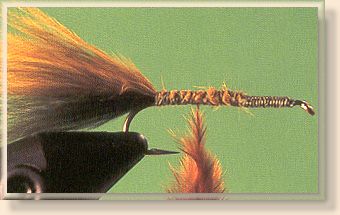

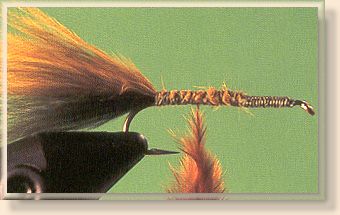

6. Prepare a pheasant rump feather by stripping the flue from the

base of the feather. Grasp the feather by the tip and sweep the

fibers downwards to expose the tip. Tie the prepared feather in by

the tip. Trim the excess material and wind the feather 2 to 3 times

around to form the hackle. Don't overdress the pattern. Tie off the

pheasant rump feather and trim the left-over material. Sweep the hackle

fibers rearward and hold in position to expse the hook eye and head

area. Build a neat neat. Whip-finish and apply head cement. Do

designate a weighted pattern place a dab of red nail polish on the

hook eye. Be careful not to close the eye of the hook accidentally

with the polish. ~ Philip Rowley

|