Woodards Dragonfly

By Alan Shepherd, Tasmania, Australia

Tied and photographed by Richard Komar, Texas

I read with great interest, postings on the FAOL

Bulletin Board, about dragonflies and bass. After

reading the postings, I realized that this particular

pattern and information; although concerning trout,

may be of great interest to bass anglers as well.

Being equipped with large compound eyes, dragonflies

are extremely sharp-sighted hunters. Like damselflies,

dragonflies are usually found patrolling rivers, lakes

and ponds, catching and eating a lot of little bugs.

However unlike damselflies, dragonflies can stray some

distance from water. Some species of dragonfly can fly

at speeds that approach 40 miles per hour. Dragonflies

are big insects, they swoop at their prey plucking it

from the air with their legs. Also they can fly forwards,

backwards, and hover, sort of like a helicopter only much

more maneuverable.

To a trout, an adult dragonfly represents a good meal.

When a trout eats a dragonfly, it gains in one mouthful,

all the nutritional value the dragonfly has captured and

eaten. Therefore, to a trout, a dragonfly is worth spending

energy to catch. Why spend all that energy in eating little

bugs when all you have to do is, be an expert jumper and

on target?

Consider the mechanics that must go on in the trout body

to accurately capture an airborne dragonfly. First it must

spot its prey by cruising or patrolling its beat. When a

dragonfly eventually comes into its field of vision,

immediately the trout begins stalking its prey. As the

dragonfly flies around erratically close to the surface,

hunting prey, it almost goads the trout into attacking.

Instantly the trout begins to track it, hopeful of that

favorable moment. The trout fins come into play, propelling,

steering and zigzagging as it follows the fly. The instant

when a dragonfly hovers in one spot - the missile trout

is launched, it is the opportune time for to attack. If

the fish hesitates the dragonfly will surely move.

It is a spectacular sight to witness trout launching

themselves clean out of the water like a accurate missile,

taking dragonflies on the wing. There is nothing more

exasperating than to be in a situation where you can

see the fish, often big fish, but no matter what fly

you cast to them, they ignore it with utter disdain.

I remember one occasion when I cast a beautiful pattern

I had spent hours making. Well it worked all right; it

was very attractive to another dragonfly that perched

on top of it. I don't think the dragonfly saw it as a

sexual partner; rather it saw it as a convenient place

to perch. Almost instantly a trout attacked it, somehow

coming completely out of the water taking the natural,

but leaving my concoction of fur and feathers still

sitting there, not even touched. So much for that fly,

back to the drawing board. These are the mystifying ways

of trout on those really hot sultry days when they become

keyed into taking nothing else but airborne dragons and/or

damsels. Dragonflies and damsels can't actually land on

the water like smaller insects such as mayflies or caddis

without becoming trapped. On rare occasions one may end-up

on the water where it will partially sink, trapped in the

surface film with wings in the spent position. Even a fly

representing a dragonfly trapped in the surface film is

usually ignored by trout, so how should one fashion and

fish a dragonfly?

Dick Woodard was a creative trout angler and fly dresser

in Tasmania in the 1970's. He approached the problem from

an entirely different perspective. Dick concentrated on

presenting his fly as an egg-laying female. He would cast

it again and again to an area where a trout worked a regular

beat. He would only leave the fly on the water for four of

five seconds before lifting it and casting again. Dicks

concept was that the arrival of his enormous fly, got the

trout's attention, much the same as with grasshopper

fishing although in this case, there is no need to thump

it down, just the size of the fly alone will announce its

arrival to any trout in the area. Because trout stalk

dragonflies flying erratically close to the surface,

where possible cast near a natural dragonfly. A trout

may actually be lurking underneath - stalking that very

fly. When your imitation fly lands the trout may react on

impulse and before it knows what it has done, reacting

to some ancient impulse it has engulf the fly. Woops!

Worldwide there are about 6,500 different species of

dragons, with around 500 species in North America. It

is not surprising to find that color and size varies

greatly. Depending on the color of a particular species

in your part of the world, you may wish to change or

experiment with the color of the cock feathers used

in making the 'Woodards Dragonfly.' Consider the fact

that you are representing an egg-depositing female and

females are not as vividly colored as the males. After

all, the presentation of this fly is the important thing;

the fly is only impressionistic. Below is the original

pattern given to David Scholes by Dick Woodard for

publication in his 1988 book Ripples Runs and Rises.

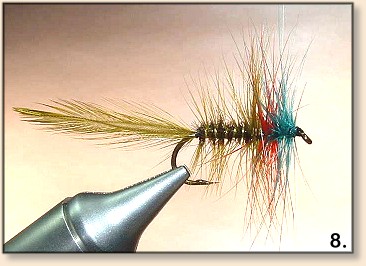

Materials List: Woodard's Dragonfly (Dick Woodard)

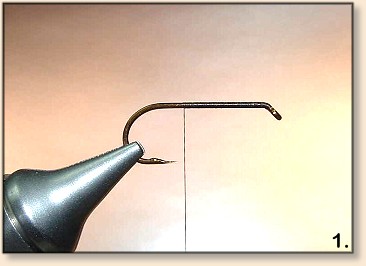

Hook: Size 4 down-eyed dry fly hook.

Thread: Black.

Tail: 2 cock feathers dyed dark green.

Rib: Yellow 'Pearsall's' floss silk, ½ strand.

Body: Three strands of peacock herl.

Body hackles: Cock feather dyed dark green.

Main hackles: 1 cock feather dyed dark green,

1 cock feather dyed red and 1 cock feather dyed dark blue.

Head: Build up with black tying thread.

Tying Woodard's Dragonfly

1. Lock in thread at head and wrap 2/3 of shank towards the bend.

2. Strip the base of the 2 green hackles. Measure them

so they protrude out the back the same length as the hook,

concave sides on inside. Bind in the storks by wrapping

tying thread to the bend. Run thread under tail twice and

varnish with a drop of head cement. Also put a drop of

varnish on the hackle tips cementing them together; this

stops the fly acting like a propeller when casting.

3. Tie in rib and peacock herls. Run thread 2/3 up shank.

4. Wind on the peacock herls 2/3 up the shank forming body.

Tie in and cut off excess.

5. Tie in body hackle dry fly style and wind back to tail.

6. Now rib the fly locking in palmered hackle. Tie in

end of rib and cut off excess.

7. Tie in the main hackles green and red with concave

side facing forward, dry fly style. The blue hackle

has the concave side facing back. First wind the green

hackle, then the red and then the blue.

8. Build up the head and whip finish.

|