Brown Woolly Bugger

By Dave Hughes

The largest mayflies fall into the burrowing category. Some reach

two inches long when they're mature, and make quite a mouthful

for any trout. Many, such as the eastern green drake (Ephemera

guttalata) and midwestern and western Hex (Hexagenia

limbata) have two- or three-year life cycles, meaning the

nymphs are out there all year long in one instar or another. Trout

always feed on them when given a chance at them.

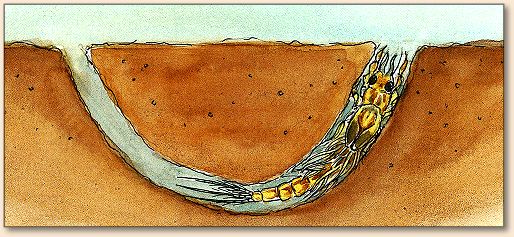

Burrowers, as their name implies, either dig tunnels into mud,

marl, and clay bottoms, or work their way into sand or gravel

bottoms until they're out of sight. They come out to forage

along the bottom only at night, which limits the time they're

available to trout, and also the time that they're useful as

the basis for imitations, to the hours of darkness.

When mature and ready to emerge, burrower nymphs leave their

tunnels or free themselves from the sand and gravel, then swim

boldly to the top, where the nymphal skin splits in the surface

film and the dun escapes. This, like their feeding, usually

happens after dark, though on a gloomy summer afternoon, say a

day with thunderheads lowering and darkening the sky, they

might begin emerging two to three hours before dark.

Though many more imitative dressings have been devised for these

large nymphs, it's difficult to beat a Woolly Bugger in the

appropriate size and color to resemble the natural. The

marabou tail undulates in the water, and represents the swimming

motion of the natural more realistically than the most exact

but lifeless imitation might. With any insect that swims briskly

and emerges in poor light, it's more important to copy the movement

than it is the precise shape.

Materials for the Brown Woolly Bugger:

Hook: 3X long, size 6 - 12.

Weight: 15-20 turns lead wire.

Thread: Brown 6/0.

Tail: Brown marabou with a few strands of red Krystal Flash.

Hackle: Brown hen, palmered over body.

Body: Brown chenille.

Tying Instruction for the Brown Woolly Bugger:

Step 1: Fix hook in vise, layer mid-shank with lead wire, and

layer working thread to the bend. Measure a clump of

marabou the full length of the hook, and tie it in at the

bend of the hook. You can also tie the marabou long,

then pinch it off at the right length. Tie in 4 to 8 strands

of Krystal Flash, just short of the marabou length.

Step 2: Tie in the body chenille at the bend of the hook.

Select a hackle with fibers about two times the hook gap.

Tie it in by the tip, with the concave side against the

body. Leave room for one turn of chenille behind the

hackle tie-in point. Take your thread forward to the

hook eye.

Step 3: Take a turn of chenille behind the hackle, then

wind the body forward in front of the hackle to the hook

eye. Tie it off and chip the excess.

Step 4: Wind the hackle forward in evenly-spaced turns to the

hook eye. The hackle fibers should tend to flare back, not

forward. Tie off the hackle stem, clip the excess, form a

neat thread head, and whip-finish the fly.

I've often set up aquariums with Hexagenia nymphs

and attempted to take photos of them swimming. I always fail

because they are able to move so swiftly. They propel themselves

with an up-and-down undulating motion of the entire body, no

doubt helped along by their fringed gills and tails.

Woolly Buggers, because of their marabou tails, do an

excellent job of imitating the movement. Though other food

forms are not the subject of this book, Woolly Buggers also

move in the water like pollywogs, leeches, damselflies, and some

baitfish, all of which trout enjoy eating when they get the

chance, and all reasons that these flies should have a place in

your fly boxes. I'd recommend you carry them in olive, black

and the listed brown, weighted, on size 6 to 12 hooks.

~ Dave Huges

Credits: The Brown Woolly Bugger is from

Matching Mayflies, by Dave Hughes, published by Frank Amato

Publications, (2001). If you plan on attending the Michigan

Fish-In, you should tie up some of these. ~ DLB

|