Harts Skwalla Stonefly

Fly and Photos by Benjamin A. Hart (benjo)

Missoula, MT.

Spring's breath of life into Montana rivers

is a much anticipated event amongst fly-fishermen,

and most everyone else in Montana save for the

powder-hounds and snow bunnies. Until spring,

those brave enough to weather icy guides and

frozen wader-boot laces have enjoyed limited

success, sometimes on midges, mostly on sub-surface

flies. Balmy days bring forth one of the best

hatches of the year: the skwalla stonefly.

The hatch is the first of the "larger" foods

available to trout on the surface and anglers

take notice. Fishing a size 6 or 8 fly on the

tail of winter is a hard to suppress secret

here in Montana. There are plenty of great

rivers to fish the skwalla hatch on but there

is no better place to fish it than on Montana's

Bitterroot River, characterized by it's slightly

warmer temperatures, incredible trout cover and

abundance of insect life.

The Skwalla stonefly is an average stone, living

life as nymph for only one year feeding on debris

in on the river-bottom and emerging sometime

between the middle of March and the middle of

April. The Skwalla doesn't win many popularity

contests amongst the other stones, most of them

hatching at a better time of year for Montana

travel. It's not as terrifying as the salmonfly

or as predictable as the goldenstone, but to many

fishermen remains the most rewarding to be on the

water for. Many factors determine angler success

during the hatch. Unpredictable colder weather in

the spring can make the bugs disappear for a while

only to reemerge a few days later. A few warm days

can melt high elevation snow bringing cloudy water

that will turn the fish off. Anglers seeking out

the hatch should observe closely, asking these

questions: Are there exoskeletons on rocks near

shore? If the answer is yes, chances are that

trout are still looking up for a meaty skwalla.

Are there skwallas in the air? Seeing a skwalla

in the air or on the water is the main indicator

that the hatch is on. Unlike salmonflies and to

a lesser extent golden-stones, skwallas rarely

hatch in droves, and seeing one on the water or

in the air is reason enough to tie on one. If you

see some around, the trout have taken notice too

and will be looking for them. Taking the time to

look closely can make all the difference in the world.

Unlike other stonefly emergence, the skwalla

doesn't follow any particular pattern and fishing

on the Bitterroot could be the just as good on

any stretch of river on any given day. Anglers

don't have to chase skwallas upriver so pressure

from fishermen isn't as much of a factor as on

other rivers during more noted hatches, and

shoulder season traffic means it's reasonable

to expect to have a beat to yourself especially

with a little walking. The Bitterroot has miles

of braided channels that are not to be overlooked

during this hatch. One can work braid after braid,

never seeing a boat or another angler, always with

the chance of hooking truly large fish. Fish will

be holding in likely water and distributed throughout

the river, from a riffle two feet deep to a rip-rap

bank or a root filled undercut, if a spot looks

suspect it's worth a cast. Really any water deep

enough to hold trout can, and probably does at

this time of year, so you're better off staying

away from the bigger, slower pools, which

incidentally, is about the only place you'll

have any competition.

Western Montana fly tiers have probably concocted

more skwalla patterns than any other. Many have

looked forward to little more than the skwalla

hatch all winter long while huddled over piles

of tying materials. Most successful patterns

have the same key elements. When caught in the

current a natural skwalla rides very low in the

water, and good patterns imitate that. Many

patterns are tied in a drop down style, sometimes

on a bent shank hook that forces the abdomen of

the pattern to ride well below the surface. This

style not only coaxes more fish to eat it, it

also guarantees more hookups. Patterns made of

foam designed to ride flat often produce strikes,

and are a necessary addition to any box. For more

turbulent water the fly of choice is a parachute

pattern with a large poly-parachute, easily seen

and able to float all day. Often a looker might

say hello to a pattern and decide something is

wrong, having other patterns on hand is critical.

If a fish denies your fly, quickly tie on a different

style and cast for the same fish, you'll often get

that fish.

Planning a trip to the Bitterroot can be a little

dicey. With runoff imminent it becomes hard to

plan a trip far in advance. High elevation snow

will melt and blow the river out a little bit

here and there, but the clarity and fishability

will bounce back in a few days. Keep in mind

that the upper river is relatively small and

a change of a few hundred cubic feet per-second

(CFS) of water represents a drastic increase in

the volume of water in the river. On the lower

river such a change is not as much of a factor.

The best advice for planning a skwalla trip is

to watch the weather, check the stream flows at

https://waterdata.usgs.gov/mt/ and check the

weather forecast even though it's rarely right

for the region. The worst that could happen is

a change of plans for a day on Rock Creek, The

Clark Fork or Blackfoot Rivers, all in the area

and all wonderful fisheries. Finally, give

yourself time. With dynamic conditions your

best ally is a few extra days to try another

fishery while you wait for the Bitterroot to

come into its own.

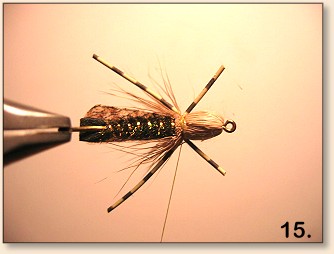

Materials Harts Skwalla

Hook: Daiichi 1270, Size 4.

Underbody: Craft foam, a tapered

rectangle and hanging out the back to make

the egg sack.

Body: 7 or 8 strands of peacock herl,

counterwrapped with fine gold tinsel.

Wing: Montana Fly Company Etha-Wing

Material "Mottled Web".

Head: Deer Hair, a little smaller

diameter than a pencil.

Legs: Montana Fly Company Green

Barred rubber legs.

Post: Foam.

Notes: The hook size is critical to the success

of the pattern, I know it appears to be the wrong

size. The Tapered foam underbody gives a good

profile and it's best to not wrap it too tight.

See attached photos.

Tying Instructions: Harts Skwalla

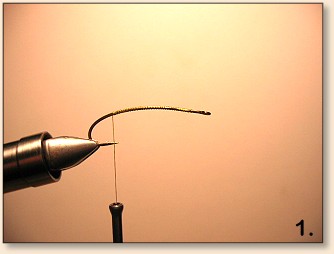

1. Start thread on hook leaving the hook bare

near the eye, this will make it easier to spin

the hair on later.

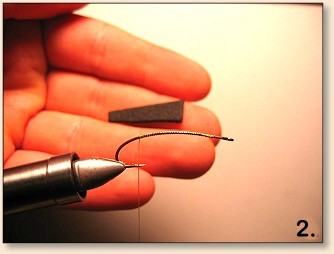

2. Take thread back so it hangs down right

in the middle of the barb.

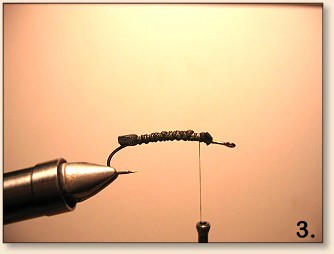

3. Cut out a long tapered rectangular piece

of craft foam and bind it to the hook leaving

a little bit poking out to be the egg sack.

Don't bind it too tight to trap air pockets

and help the body taper.

4. On your way back to the rear, bind down a

small or extra small piece of mylar tinsel.

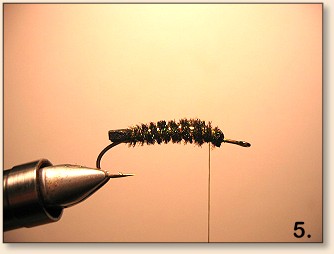

5. Tie in 7 or 8 strands of peacock herl at

their tips. Wind them forward and counterwrap

with the tinsel.

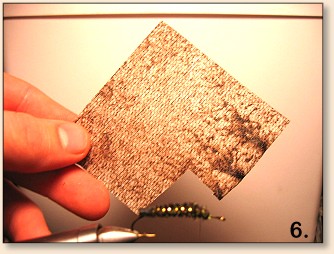

6. Cut out a stonefly shaped wing from Montana

Fly Company etha-wing material and bind it down

on top of the abdomen.

7. Stack, clean and spin a clump of deer hair

about the size of a pencil at the eye of the hook.

8. Pull back deer hair to make bullet head.

9. Clip the deer hair on the bottom.

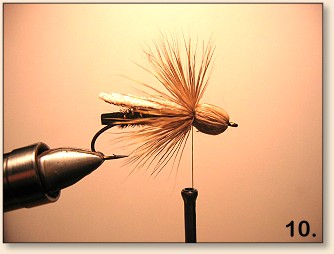

10. Add Montana Fly Company centipede legs, or

similar and add post, I prefer packing foam

that you sometimes find on DVD players and

other electronics.

Top View:

Fish-Eye's View:

More!

I developed this pattern a few years ago in my

search for the perfect blend of visibility,

general lifelikeness, and readily available

materials. I gave a few to my good friend Nick

and he called me that night to tell me that he

caught 40 fish on one fly. The Hart Skwalla was

born and has since taken many picky fish on the

Bitterroot and other rivers. I chose the hook style

because I wanted the body to ride low in the water

because fish will often short strike a skwalla

pattern. I also opted for a hook one size bigger

than the pattern to drop that point down even more.

Don't forget to grease the deer hair and the top of

the wing, and tight lines. ~ Benjamin A. Hart (benjo)

|