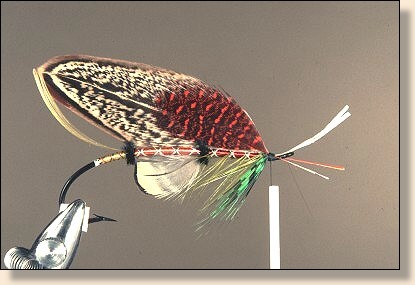

Lesson 1 - Cheap Atlantics

This lesson will be the most challenging one yet for novice Tyers.

It involves a lot of techniques not used in other types of tying so

in some ways even accomplished Tyers of some styles of tying will

share some of the same frustrations as new Tyers. I will show you

how to make feathers in particular do things contrary to their

structural makeup. The patterns in this part of the series are

not overly complicated. I don't want to give you patterns at

this stage of your tying that will be overly frustrating to you

and run the risk of turning you off to tying these flies. There

will be quite a lot of new things to learn here but, many of the

basics we have already covered will be used here as well. A big

part of tying these flies for myself and just about every other

Tyer of these kinds of flies is the challenge of overcoming often

stubborn materials, to create a fly that is easy on the eye and,

to continue a very old tradition.

I originally came up with a series of "cheap" Full Feather Wing

Salmon flies a few years ago to utilize some of the many beautiful

feathers found on various Gamebirds, Ducks and, some of the more

common Pheasants. Another reason for doing them was an attempt to

show Tyers that they can tie beautiful full dressed flies without

spending a ton of money and, often with materials you already have.

This fly will hopefully encourage you first to try tying the full

dressed flies and, second, to look at everything with the question,

"will this be useful as tying materials?" I have even used strands

of a copper scrub pad as tinsel before. This particular fly has

been tied using 100% inexpensive and available materials. If you

don't have the exact feathers or, other materials, substitute

similar ones. The three patterns I am presenting in this lesson

are fairly simple in their construction and number of parts. Later

in the series, we will tie some much more complicated full dressed

flies. The techniques presented here will allow you to tie just

about any full feather wing Atlantic Salmon fly either simple in

design or complicated.

I will guarantee once you have tied one of these flies, you will

have embarked on a new and exciting tying journey. Tying full

dressed flies is probably the most satisfying and challenging

of the craft. Having said that, it is not necessarily that much

harder than other styles once you have learned the "tricks" and

techniques.

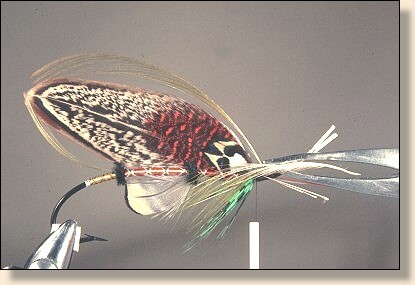

Matching Feathers For Full Featherwings

When you are matching feathers for flies that use the whole

feather for the wings, great care in matching will make the

task of setting the wing either easy or difficult. It can

also prevent wings that flair to one side or twist out of

shape.

When I first started to collect my "special" feathers and before

I had actually begun to tie full featherwing flies, my routine

for matching was simple. First, look at the outline and match shape.

If the curve of the feathers shafts didn't curve in the same

precise direction and follow the changes exactly down the shaft,

I didn't see as all that important. So, I had all these feathers

matched and in labeled bags ready for me to tie with. I soon

found out that trying to make two dissimilar feathers behave as one,

no matter how slight the difference, is difficult at best and

near impossible at worst.

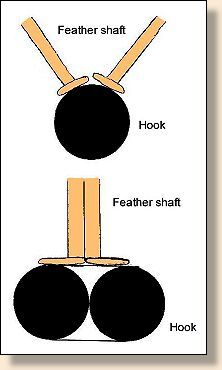

My matching criteria now is a three step test. A feather passing

all three qualifies as a matched pair. Two of three tests relegate

the feathers as non-pairs. First, I select two feathers whose

outline, curves and, length look the same. Second, I place them

together good sides out and, hold them up to a bright light. If

the outsides match exactly and, the shafts are also matched exactly,

it passes the second test. Third, while still holding them together

with my right thumb and index fingers, I flick the "wings" with my

left index finger rather hard. If the feathers do not move any

amount, they pass the third test. Now and only now, they qualify

as a matched pair. I then put a dab of hot glue on the bottom tip

of the feathers to stick them together and bag them for later use.

One other visual thing to look for in matched feathers is that the

wing will be perfectly straight but, this is a natural result of

the three tests so, doesn't qualify as a fourth test. If the barbs

curve unnaturally even a little, you can be assured there is a

conflict somewhere.

If you really look at feathers, you will see some amazing structures

that are incredibly strong for their weight. Every curve has evolved

to produce maximum strength. This is especially true of the wing

feathers that are some of the more frequent feathers used for full

featherwing flies. If you have a pair of feathers that for every

purpose match but, one is a little shorter or, slightly more or

less curved than the other, you will have one feather that is,

for lack of a better term, stronger or weaker than the other.

When you assemble these two dissimilar feathers, a conflict arises

and the stronger feather will win. You may be able to finish a fly

that looks great with such a pair of feathers, but the slightest

disturbance will make the feathers move to the path of least

resistance. The wing will "blow up." If this happens, the options

are limited to none. A little more careful matching could

save that one of a kind creation and, all the work that goes into

putting it together.

Before we get started with this lesson, let me explain how I go

about creating a Full Feather Wing Fly. Almost 100% of the time,

I choose the wing feathers before any other component of the fly

including the hook. Some Tyers will go by an existing pattern and

others will draw the pattern as they want to tie it. I have never

been able to end up with a fly that I have tried to draw out and

choose all the materials beforehand. Some may be able to do it

this way I can't seem to make that approach work for me.

Assorted matched feathers for full featherwing flies

I have boxes of matched feathers that over the years, I have

either plucked pairs of feathers from a skin or, sorted through

countless thousands of molted feathers (a grueling and time

consuming process in itself). Most of these feathers have been

washed and attached with a dab of hot glue on the bottom end

of the shaft to keep the pairs together. Then I have pairs of

like feathers in zip-loc bags and, these in plastic boxes.

Over the years I spent literally, thousands of hours sorting,

washing and, matching feathers. All of this time pays off when

I am ready to tie a fly though.

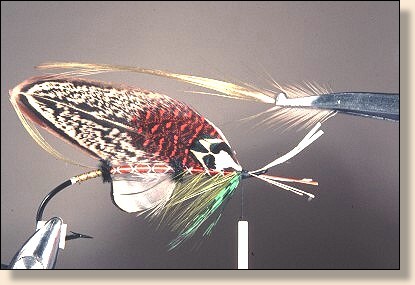

When the inspiration to tie hits me, I go to the matched pairs

boxes and, go through the various bags of feathers until one or

more jump out and, say, "use me, use me!" Then, I lay them all

side by side and determine which "speaks" the loudest. That one

is the cornerstone of next fly I tie.

Now that I have the rough wing, I select the hook of the shape

and size that will best show the beauty of the feathers of the

wing. While choosing the hook size, I start to get a rough idea

of the length of the wing. I strip away much of the fluff at the

base of the feathers to get it out of the way but, not before

careful consideration. All the rest flows from these two components.

The colors of the fly are determined by the color/colors of the

wing and, the "style" of the fly is determined by the shape of

the wing. It's these first few steps that are the most important

in my tying a Free Style fly.

It will take you a few flies to begin to understand the limitations

of the materials, the different feather types and, the mechanics

of their structure and, how to make it all work together for you.

Sometimes a material simply has a "mind of it's own" and, all the

tricks and techniques will simply not make it conform to your will.

These times need a different approach. Let the peculiarities of the

material work for you, not, against you. This is when you need to

think "outside the box." What is the structure of the material that

can't be changed without a detrimental effect on the final look of

the fly? How to make that problem be part of the solution?

Throughout this series you will see flies with unusual materials,

uses of materials and often unusual combinations of materials. To

me, my materials are my paint, the hook my canvas. If you don't

have the materials to draw upon, your finished "painting" will be

bland and uninteresting. This is not to say that, the fly needs

to have wildly bold and bright colored materials to be a great

looking fly however. It means you may have a fly that seems incomplete

or lacking something.

I am sure you have seen flies that have tons of parts sticking

out in all directions and, at first they are amazing to look and

marvel at. Sometimes though, a fly can have so many parts that it

renders it confusing. What is the focal point? Where does one

material end and the next begin? In my view, a successful display

fly needs to be a "quick read." By that I mean you needn't look

at the fly for an extended period of time to figure out whether

or not you like it. It either "speaks" to you or it doesn't. But,

since we all like different things, not every viewer will react

to the same flies in the same way. So, that brings me to the second

step that I mentioned in the introduction, "The real intent is to

have fun tying". Do what you enjoy tying, develop your own individual

style of tying and the rest will take care of itself.

If you find that you like tying the Full Feather Wing Atlantics

and/or the Free Style flies, you will be doing yourself a huge

favor if you try to buy full skins to work from. There are a huge

number of feathers that you will never see in fly shops that are

on full skins. Even when you do find full skins, it is likely that

they trimmed any number of feathers off when it was skinned. When

I get dead birds and skin them myself, I take great care to skin

them as though it were going to me mounted. I leave the legs and

all the head feathers on. Many of these make wonderful veilings

for my flies. If you hunt or, know hunters, let them know you

will take any birds they don't want. Even if they don't want to

give up the birds, maybe they will save the plucked feathers for

you.

In any case, keep an eye out for feathers because you just never

know when an opportunity of a lifetime will pop up.

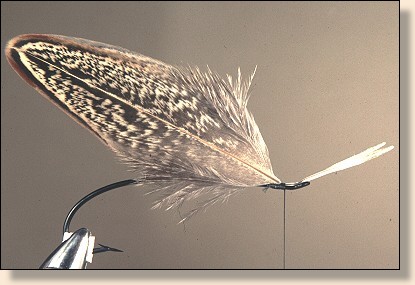

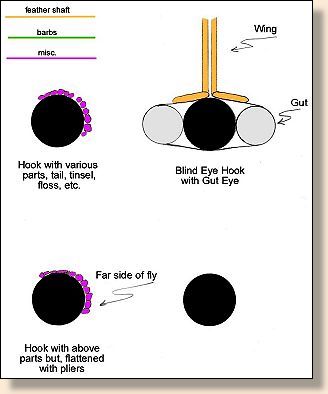

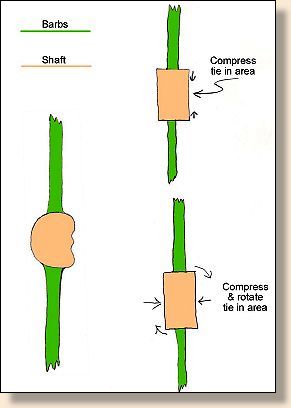

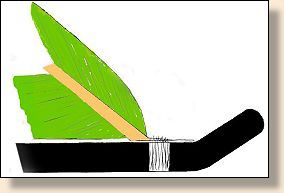

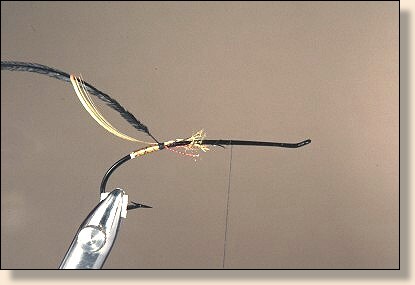

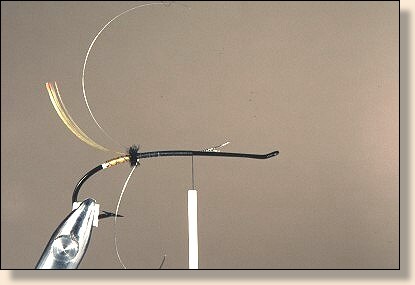

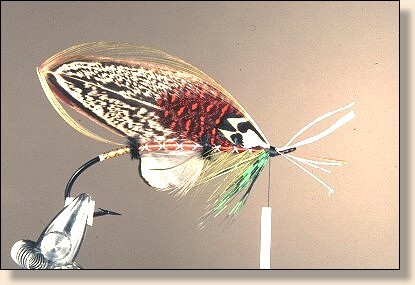

A. Prior to removing any part on the feathers, assess how much of

the feather you want to use for the finished wing. Remember that

some will be covered by other materials along the sides near the

head. I try to use as much of the "good area" of the feather which

is usually the upper part. Now, select the hook for the fly. You

have already established the basic wing size/length/shape so, just

match that to the correct hook size and shape. Strip the fuzz from

the base of the feather to a place just short of the actual wing

size. If the feathers are of a type that can be tied in and stay

tightly together with their curves canceling each other out, lay a

temporary thread base at the wing tie in area. Now, you can strip

a little more fuzz away until you are at or just about at the final

wing size and tie the wing on temporarily. You can "fine tune" the

length of the feathers before you set the wing in place for the

final time.

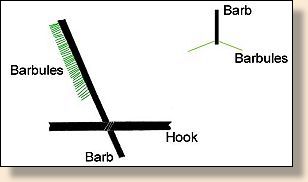

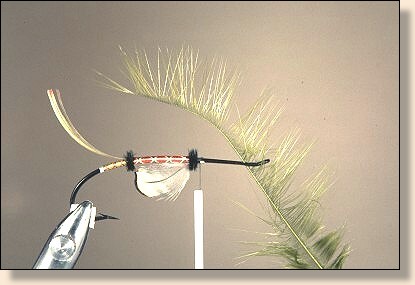

A word on feather fuzz; some feathers have barb shapes that when

the fuzz has been stripped up to the "good area" the shape of the

wing will have a shallow curve at the base of the wing which will

accommodate the topping easily. Other feathers have steep curves

that make adding a topping difficult at best and, impossible at

worst. It is much easier to plan and select the topping at this

point rather than ending at the front of the fly with no easy

topping solution. If you had planned to put a topping on, selected

and tied in the tail which anticipated meeting the topping, and,

it turned out impossible to select a topping that would accommodate

the wing, the tail may look odd back there all alone! In such a case,

that tail may be too long and a shorter one or another material would

look more appropriate. Some wing shapes simply will not accommodate

a standard topping so alternatives must be found. Sometimes, a short

partial topping can be used to good effect or, none at all. Leaving

some or all of the fuzz on can actually enhance some wings. I have

said it before, "think outside the box" to find solutions to problem

materials. Make their structures and looks work for you rather than

against you. You are going to get tired of hearing this but, for this

type of tying, it can make the difference of a fly that works and one

that falls flat.

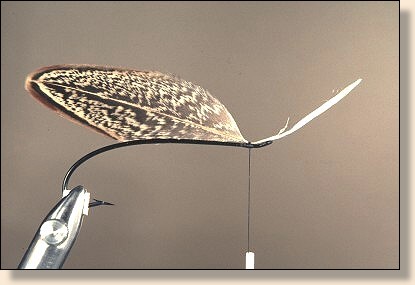

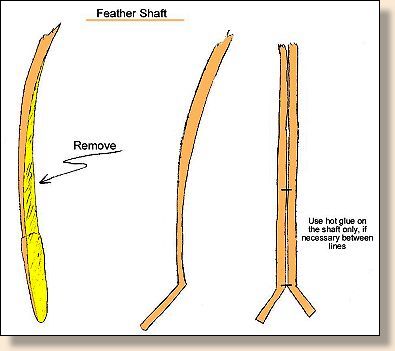

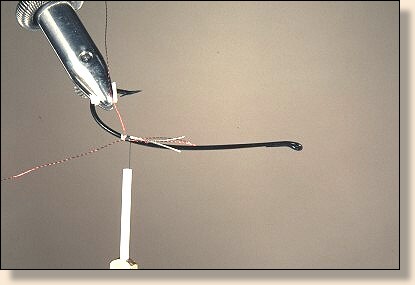

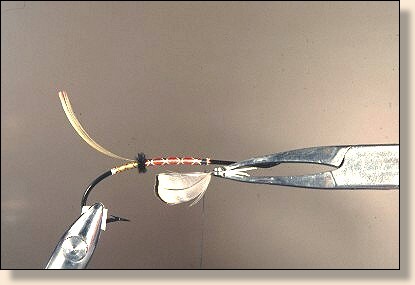

On this fly, I will not be leaving any of the fuzz on the wing.

With that decision made, we have the question of how to remove

the fuzz. We have two alternatives. One is to strip the barbs

with the fuzz away but this "eats" up much of the wing length.

We also do not want the shank of this hook to be hidden anymore

than absolutely necessary so, we would have to strip away a

lot of the barbs to the point of where they no longer cover

the shank. Well, as you can see in the illustrations, this

leaves a sizable void underneath the wing. That void will need

to be covered somehow and that can be very difficult to do. It

will also leave an area that will not provide a base to lay our

sides, cheeks or, shoulders onto. So, these parts will want to

go in every direction in those areas. One solution is to VERY

carefully and, with very sharp scissors, cut the base of the

feather in the shape you desire. This procedure can be very

tricky to do without wrecking feathers. The blades of the

scissors can and will push the barbs ahead of the cut so the

resultant edge is sometimes uneven. Since these areas will be

in plain view, uneven edges will ruin the look of the fly. So I

recommend practicing cutting similar feathers until you have a

good degree of control. It is best to take care of this step now,

at the beginning of tying the fly. If you wait to trim the wing

until you are ready to tie it in and mess it up then, you will

be one unhappy camper especially, if these were your only two

wing feathers like them. Easier to find another wing now in

the event you make a mistake.

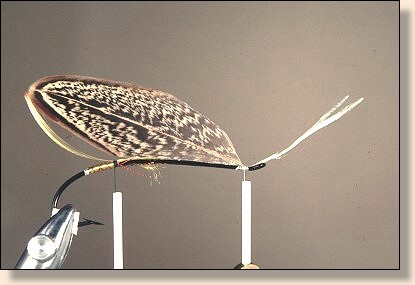

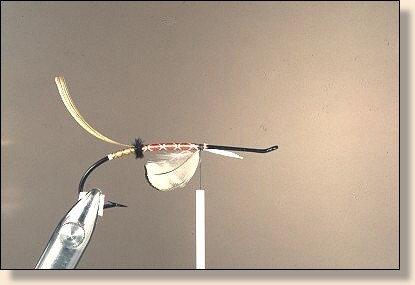

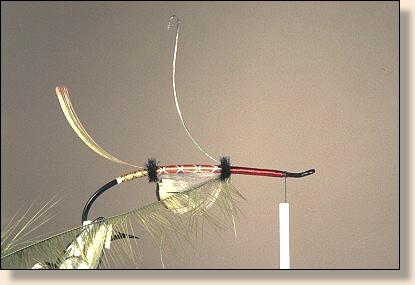

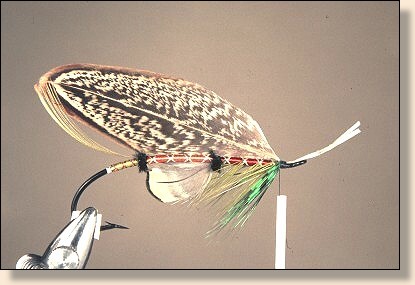

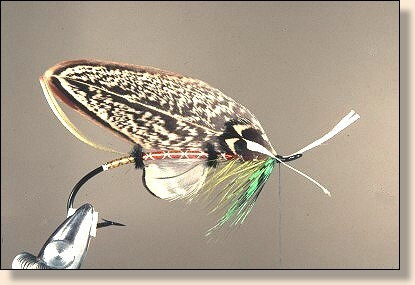

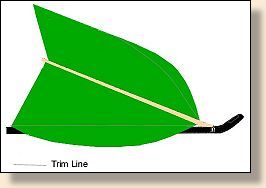

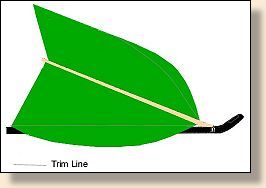

Wing feather shape prior to trimming and, showing the ideal

shape indicated by the trim lines.

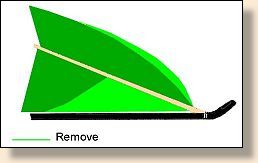

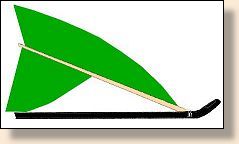

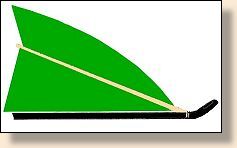

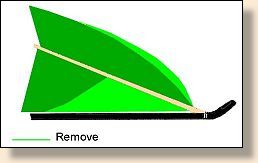

Wing feather showing the potential areas to be removed or, modified.

|