Old Rupe is "off his feet" for a while, and we will fill in

for him the best we can. If you are knowledgeable about a particular

insect or local hatch, please help us out - contact:

LadyFisher.

Don't worry about photos, we have good references.

The sight of a caddis hatch excites more than the fish - it excites the fly fisherman too!

And well it should. Caddis are found nearly everywhere in the world, and in the US

some 1200 species have been identified. They live in all forms of moving or standing

fresh water, which makes them available to stream and lake fishermen. Caddis are

members of the order Trichoptera designating they have hair-covered

wings. The tip-off in identifying caddis is the tent-shape of the wing.

Caddis in general start hatching in numbers in early spring (see

Little Black Sedges)

with the next big hatch being the Grannoms. We

have covered the life-cycle of caddis in previous articles here, suffice

to say there is hardly a time on any stream

when a caddis isn't available in one form or another.

The Cinnamon Caddis - Hydorpsychidea (also called the

Spotted Sedge) happens to be one of my favorite caddis hatches. We

have fished it extensively in Michigan and Montana. We found some size

difference between the two places, which may have to do with the very

cold, long Montana winters. It is a very important hatch. Carl Richards

and Bob Braendle in their great book, Caddis Super

Hatches list this hatch as one the Caddis Super Hatches of the Eastern

United States: "Most important genera of all Tricoptere all season,

usually evening emergence but can come in early morning, sometimes has a

light morning and heavy evening emergence." They recommend sizes 16-18

flies.

The Cinnamon Caddis - Hydorpsychidea (also called the

Spotted Sedge) happens to be one of my favorite caddis hatches. We

have fished it extensively in Michigan and Montana. We found some size

difference between the two places, which may have to do with the very

cold, long Montana winters. It is a very important hatch. Carl Richards

and Bob Braendle in their great book, Caddis Super

Hatches list this hatch as one the Caddis Super Hatches of the Eastern

United States: "Most important genera of all Tricoptere all season,

usually evening emergence but can come in early morning, sometimes has a

light morning and heavy evening emergence." They recommend sizes 16-18

flies.

They again list the Cinnamon Caddis as a Super Hatch for the Midwestern

United States, again in sizes 16 -18 calling it: "Extremely important over

entire season." For the Super Hatches of the Western United States:

"Most important family of all Tricoptera by a wide margin during the

entire season, and most important genus, usually evening emergence but

can come in the morning."

One of the things which made this such an important hatch is the numbers of

insects available to fish. The Cinnamon Caddis is one of the 'net-builders' which

spin a net out of silk and catches their food in the net. They mostly stay in the same

place, attaching themselves to a likely spot with the same silk. If the food supply

doesn't seem adequate in one spot they will detach themselves and drift downstream

a bit. If another larva invades their lair they will fight for the space!

One of the things which made this such an important hatch is the numbers of

insects available to fish. The Cinnamon Caddis is one of the 'net-builders' which

spin a net out of silk and catches their food in the net. They mostly stay in the same

place, attaching themselves to a likely spot with the same silk. If the food supply

doesn't seem adequate in one spot they will detach themselves and drift downstream

a bit. If another larva invades their lair they will fight for the space!

To fish the larva form of this insect, you need a weighted larval imitation,

(the actual larva forms between 1/4 and 3/4 inch in length) which is fished drag

free on the bottom, using a long leader and floating line.

For stillwater, fish your weighted fly very slowly on the bottom in waters less

than 20 feet - again using long leader and floating line.

After the transformation from larva to pupa, the pupa emerges from the old case

and drifts downstream. Or in stillwaters simply swims to the surface of the water.

The emerging adults are very accessable to the fish. I'm sure you know the figures,

a trout takes 9 nymphs or emergers for every dry fly. Probably something to do

with availability. Caddis are very important food sources for all game fishes!

If I were a panfisherman and saw caddis hatching, I would sure try a pupa

imitation and then the adult dry to match it. To fish this part of the emergence,

use an upstream nymphing or down-and across method, staying close to the

bottom and lifting your rod at the end of the drift to match the swimming to the

surface by the real pupa.

Al Troth's Elk Hair Caddis is a fish catcher, no question about it. The reason

being you can tie it light or dark and match most of the adult caddis. Caddis

adults live longer than mayflies, some as long as two months! Which gives

great availability to both the fish and the fisherman. The Goddard Caddis is

another popular dry fly for caddis.

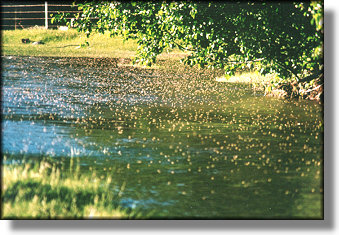

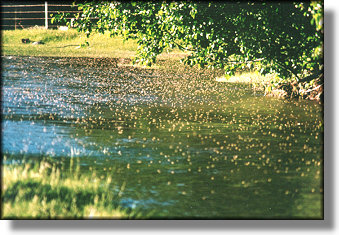

The photo on the right can be either a blessing - or not. This is a 'blanket' hatch

of caddis. You have insects, the trout are feeding - but spotting your fly

in all that mess can be impossible. The good news is the trout become absolutely

frenzied and even the big boys come out to eat. If you can find a likely seam or

drift be aggresive and tenacious and keep that fly out there. My personal fly of

choice on this hatch is the Lady's Fish Finder.

Tied with cinnamon hackle it does stand out in the mass of flies on

the water so I can see it, it skates naturally on the water, and fits the

footprints the natural insect leaves. (If you haven't been following the

Flies Only series here you're missing

important information on what flies really look like to the fish.) Keep in mind the

natural insect is trying to get off the water as fast as they can. Our

observations are caddis really don't like being on the water. The take will be

slash and jump.

Last but not least are flies for the egg-laying females. The females lay their

eggs in a variety of ways, everything from low flying with just their abdomen

touching the water, dive bombing and actually entering the water, to crawling

down anything that sticks up in the water (including fishermen) to deposit their

eggs. That yucky slime on your waders is probably caddis eggs! For caddis which

crawl back into the water, or dive in, (both of which swim back up to the

surface) soft hackled flies are recommended especially by Brian Chan.

I haven't fished them and can't do a personal recommendation on them.

I've been in caddis hatches where there were so many it was difficult to breath,

and fished caddis flies when nothing was seeming to be happening at all. Somehow

the fish knew what was happening even if I didn't. In doubt? Fish a caddis! ~ LadyFisher

For more on caddis check these out:

Photo credits: Caddis nymph and adult drawings from

Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty,

published by Jones and Bartlett, tied Cinnamon Caddis fly from

Caddis Super Hatches Blanket hatch photo by

James Birkholm.

|

The Cinnamon Caddis - Hydorpsychidea (also called the

Spotted Sedge) happens to be one of my favorite caddis hatches. We

have fished it extensively in Michigan and Montana. We found some size

difference between the two places, which may have to do with the very

cold, long Montana winters. It is a very important hatch. Carl Richards

and Bob Braendle in their great book, Caddis Super

Hatches list this hatch as one the Caddis Super Hatches of the Eastern

United States: "Most important genera of all Tricoptere all season,

usually evening emergence but can come in early morning, sometimes has a

light morning and heavy evening emergence." They recommend sizes 16-18

flies.

The Cinnamon Caddis - Hydorpsychidea (also called the

Spotted Sedge) happens to be one of my favorite caddis hatches. We

have fished it extensively in Michigan and Montana. We found some size

difference between the two places, which may have to do with the very

cold, long Montana winters. It is a very important hatch. Carl Richards

and Bob Braendle in their great book, Caddis Super

Hatches list this hatch as one the Caddis Super Hatches of the Eastern

United States: "Most important genera of all Tricoptere all season,

usually evening emergence but can come in early morning, sometimes has a

light morning and heavy evening emergence." They recommend sizes 16-18

flies. One of the things which made this such an important hatch is the numbers of

insects available to fish. The Cinnamon Caddis is one of the 'net-builders' which

spin a net out of silk and catches their food in the net. They mostly stay in the same

place, attaching themselves to a likely spot with the same silk. If the food supply

doesn't seem adequate in one spot they will detach themselves and drift downstream

a bit. If another larva invades their lair they will fight for the space!

One of the things which made this such an important hatch is the numbers of

insects available to fish. The Cinnamon Caddis is one of the 'net-builders' which

spin a net out of silk and catches their food in the net. They mostly stay in the same

place, attaching themselves to a likely spot with the same silk. If the food supply

doesn't seem adequate in one spot they will detach themselves and drift downstream

a bit. If another larva invades their lair they will fight for the space!