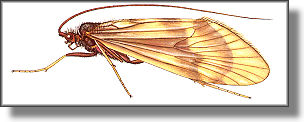

This caddis fly is a member of the Family Brachycentridae

(the tube-case makers). Here the fly I fish is Brachycentrus

americanus. This is just one of nine members of the genus.

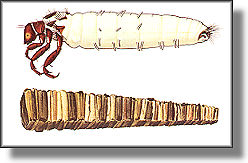

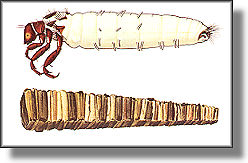

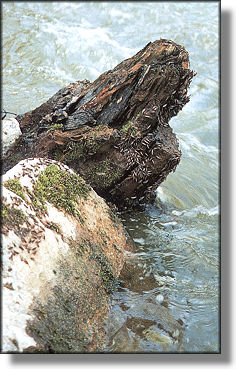

All members of this genus make cases. This larvae makes a four-sided

black case, about 15mm long, that appears to consist of wood, which

it holds together with an interior silk lining. The larvae itself has a

light green body with dark legs and a real dark head. The body, head,

and legs just peak out of the case when its active and at the first sign

of danger it pulls all of its parts back in like a turtle. It feeds by scraping

algae off the rocks by day and using its legs like a net to trap food during

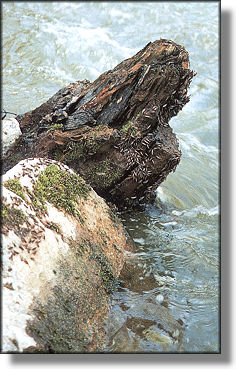

the night. The unique thing about the larvae is that they live in the rocky

riffles and anchor themselves to the rocks by a short white silk line. It

uses that line to rappel from stone to stone, the line serving to prevent

the case from being washed away.

This caddis fly is a member of the Family Brachycentridae

(the tube-case makers). Here the fly I fish is Brachycentrus

americanus. This is just one of nine members of the genus.

All members of this genus make cases. This larvae makes a four-sided

black case, about 15mm long, that appears to consist of wood, which

it holds together with an interior silk lining. The larvae itself has a

light green body with dark legs and a real dark head. The body, head,

and legs just peak out of the case when its active and at the first sign

of danger it pulls all of its parts back in like a turtle. It feeds by scraping

algae off the rocks by day and using its legs like a net to trap food during

the night. The unique thing about the larvae is that they live in the rocky

riffles and anchor themselves to the rocks by a short white silk line. It

uses that line to rappel from stone to stone, the line serving to prevent

the case from being washed away.

The pupae appears brownish green

and pops to the surface fast enough that pursuing trout will often clear

the water in the heat of the chase. The pupae may drift for long distances

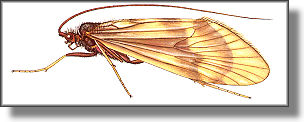

a foot or two under the surface before it pops to the top. The adult is

a brown-olive bodied fly which becomes really important during the

egg-laying process. I see the egg layers lying spent on the surface. I

believe some fail to break through the surface tension and drop their

eggs there while others that do succeed in breaking the surface swim

down to deposit their eggs on underwater objects, returning to lie spent

on the surface if they can break through the surface film. I have never

observed eggs on the spent flies. The spent flies I have observed have

laid there without movement. In other hatches the spent flies exhibited

a lot of movement.

What happened differently here? Did they all deposit their eggs under

water and the ones we observe on the surface are all returners that

never had the strength to fly off? Those that return to the surface and

fly off, which I believe some do, mate and return again to lay more

eggs. I believe this happens not only in this species but in many others

also, especially the Little Black Sedge, which interacts with this

species and the Hendrickson hatch in a complex manner. Little is

in the literature, and I have spent a lot of time searching. I attribute

the underwater activities to the fact that a sunken fly with a large

egg sac produces. The double egg-laying event or maybe triple is

an evolutionary positive thing I suspect. In the future, hundreds of

thousands of years or so, I think all or most of the surviving caddis

species will exhibit a multiple egg laying event.

I have had some limited success fishing the cased caddis in the

riffles weeks before the hatch with a ten to twelve inch drop of

the rod straight down stream. I haven't fished this way for years,

but I remember getting an opaque, white, water proof marker

from the local artist shop and marking about 20 inches of my

leader up from the fly. I only used it when nothing else was

happening, and during this time of the year that was a rare event.

I discontinued the practice when I came to the conclusion that

trout were taking the fly not as a larvae, but as a something that

might be good to eat. A poor attractor and a stupid choice. The

trout caught on cased imitations can attribute their demise to the

buggy look of the fly. Paul Young's strawman nymph is a nice

impressionistic fly in its own right. To give the devil his due I

have seen plenty of these cases in trout stomachs.

There is a complex interaction between the Little Black Sedge, a

size 18, and the Hendrickson and the Grannom which is a 16.

There is a complex interaction between the Little Black Sedge, a

size 18, and the Hendrickson and the Grannom which is a 16.

Early on in the Hendrickson hatch the Sedge precedes it, while later

the Grannom replaces the sedge. The only difference being the size

of the fly. I fish both dry caddis imitations almost always with an

egg sac as I believe the trout remember the egg laying event, into

the following day, which is the major event of the hatch. I have had

a little success with a spent Delta caddis but the fly I always return

to is the EHC size 16 which has a yellow egg sac on the terminal end.

We are all in the same pitch-pot. At this time of year there can be six

or so flies the trout are on, and wise people don't preclude the Grannom.

I fish the Grannom and the Little Black Sedge as they compliment the

Hendrickson hatch, like I should. In the early morning and afternoon

its caddis and later it's Hendricksons. I use a pupae imitation big time

during this hatch. Some accuse me of using a small split shot twelve

inches above the pupae under an indicator on bad days.

The real producer is usually a pupae imitation fished down and across,

most of the time dragging on the surface, fished with a rhythmic twitch.

Al Campbell did you patent this presentation?

When egg laying begins, a diving caddis with a pronounced egg sac

might be the thing. Fish it weighted with a series of short pulls, down

and across. An EHC that has a wing that doesn't float it in a hurricane

should work.

Here in the east be ready to switch to the Hendricksons when they

show up in the mid-afternoon.

This is not a stand alone hatch, as most probably are not, but it

should be a major component of most spring fisher's act.

This time of the year you can find trout on one stage or another of a

group of flies. There can be the leavings of the Tiny Winter Blacks,

Baetis and pseudocloeon will be there,

the Sedge and the Grannon will be in forceful attendance along with

pockets of several others.

The important thing to remember is that the same fly will come

off the same part of the stream every year. Grannoms will be

Grannoms, and they always seem to fit themselves into natures

march at the same place.

The important thing to remember is that the same fly will come

off the same part of the stream every year. Grannoms will be

Grannoms, and they always seem to fit themselves into natures

march at the same place.

Here's what I don't know:

1. Do most dive below the surface to lay their eggs? I think they do

but I can't find real observations of that event.

2. Do high concentrations of the Little Black Sedge preclude the

presence of Grannoms, and visa versa? I see Sedge riffles and I

see Grannom riffles. Why? They look the same to me.

3. Does the pupae really drift as far as the literature says it does?

Most of my fish come from a dragging fly on the surface. I suspect

the long drift may be an entomologist's dream.

4. A high percentage of my fish are accounted for by a dry EHC. The

literature say that should not be. Is it just because I fish the dry more?

I don't think so. There is a big point missing here! I tie the body with

peacock herl, or if not then I tie it black as coal.

I don't think the tie is the important thing. I believe its accessing the

correct stage of the insect at the right time.

There is a right girl to take to the dance. Old Rupe

Special credit to: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick

McCafferty, published by Jones and Bartlett for the technical illustrations in this

article. Other photos from Penn's Creek River Journal

Frank Amato

Publications, Inc.

|

There is a complex interaction between the Little Black Sedge, a

size 18, and the Hendrickson and the Grannom which is a 16.

There is a complex interaction between the Little Black Sedge, a

size 18, and the Hendrickson and the Grannom which is a 16.

The important thing to remember is that the same fly will come

off the same part of the stream every year. Grannoms will be

Grannoms, and they always seem to fit themselves into natures

march at the same place.

The important thing to remember is that the same fly will come

off the same part of the stream every year. Grannoms will be

Grannoms, and they always seem to fit themselves into natures

march at the same place.