Heaven Is A Steelhead, Part 4

By Joe Brooks

Most of us used a sinking-float line, the first 30 feet of which sinks while

the rest floats. With such a line you can make very long casts and put the

sinking section out where the fish are. It will go down quickly and allow

leader and fly to work in the holding water. The floating section is easily

mended, or flipped upstream, letting you keep the fly out there and drifting

freely. And the sinker floater is much easier to retrieve and pick up than

is a conventional sinking line.

Moses Nunnally, though he is an old hand at fly casting, had never fished

this kind of line before.

"Couldn't I do just as well with a floater?" he asked.

I explained that the fish were holding deep in the riffles and pools and

didn't seem to want to come up to take. Now and then they moved up a

foot or so, but most of the time they nosed down and picked up a fly

as it slid along the rocks on the bottom.

I'd guess 85 percent of all steelheads taken on flies are caught by the

users of sinking lines, lines that get the fly right down to the fish. Many

anglers use a line that sinks in its entirety, but an old steelheader's trick is

to splice a sinking head to a monofilament line or to a level nylon floating

line. But using a very heavy head - a 333-grain shooting head for instance -

and splicing a nylon running line to it, you get an outfit with which you can

easily make casts of 125 feet. The light nylon with float and so won't be

pulled by the current as would a heavier line.

However, the new combination sinking-floating lines, now made by a number

of fly-line manufacturers, eliminate the troublesome job of splicing two lines

together. The new lines also eliminate another problem - possible weak

spots at the splices.

Moses' first cast with the sinker-floater on the Babine was a good one of

about 85 feet. But as soon as the fly and line landed, the current grabbed the

line and put a big belly in it. I know that consequently the fly was rushing

across the pool far too fast.

"Mend your line," I said hastily. "Flip the floating part upstream so the

water won't pull on it and drag the fly away from the fish."

In any steelhead river having a fairly stiff current, the heavy push

of water will quickly belly a line and pull leader and fly out of the lies of fish.

I told Moeses to throw a slack-line cast (a serpentine toss) and tend to mend

the floating part of the line. That way, the fly floats freely for a longer

distance, straight down-current, out where the fish are.

I explained that some fishermen make a cast and feed the shooting line out

of their hands or let it run out of the shooting basket (we used shooting

baskets on the Babine) so that the fly gets down and works along the

bottom."

"After the fly has finished the downstream float and the current starts to

pull it across the pool," I told him, "let it go, keeping the rod tip high

and imparting no action to the fly. It'll work across the pool and come

to a stop directly below you."

"A steelhead may hit at any part of a float - sometimes as soon as the fly

lands, sometimes when it's out in the current - or he might follow it ]

across-current and hit on the swing. Most of them do hit on the last part of the

swing or just when the fly stops moving and hangs in the current."

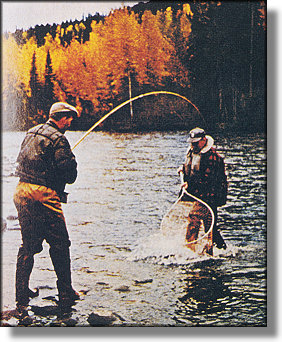

"That's what he did!" yelled Moses, who was following my instructions

religiously. "I've got one!"

"That's what he did!" yelled Moses, who was following my instructions

religiously. "I've got one!"

He raised his rod tip, and 30 feet out from us a steelhead took to the air.

It was a good, deep-bodied fish, and it fought a great fight. Moses finally

beached the trout, which weighted 14 pounds even.

"Not bad," I said. "Two casts and one steelhead."

Some steelheaders bring the line in as soon as the fly's cross-current swing is

complete. Others retrieve the fly upstream for several feet, jerking it as they

do so, before bringing it in for the next cast. On the Babine I have got hits

from steelheads on those slow, foot-long jerks, so I stick with that kind of

retrieve where I try for steelheads.

One the Babine, as elsewhere, to get the best float with a sinking line you

have to judge the water's depth and force.

Sometimes the current is so great and the water so deep that, even with a

sinking line, you must cast well upstream so that the line has time to get

down before it reaches the place where you know or suspect the fish are

lying. On the other hand, the fish may be holding where the water is

shallow and the current relatively slow. In that case you have to toss the

line and fly a bit downstream so that the line won't sink too much and catch

on rocks. ~ Joe Brooks

Concluded next time with more on tackle and techniques.

*Publisher's Note: The above story is by the late Joe Brooks,

written for OutdoorLife magazine in 1968. This excerpt is from

a wonderful book, The Best of OutdoorLife, One Hundred Years

of Classic Stories. We thank Cowles Creative Publishing, Inc. for use

permission. ~ dlb

If you missed the other installments of Heaven is a Steelhead, here they are:

Heaven is a Steelhead - Part 1

Heaven is a Steelhead - Part 2

Heaven is a Steelhead - Part 3

|

"That's what he did!" yelled Moses, who was following my instructions

religiously. "I've got one!"

"That's what he did!" yelled Moses, who was following my instructions

religiously. "I've got one!"