Heaven Is A Steelhead

By Joe Brooks

Bill McGuire was into a fish. It streaked across the pool so fast I thought it was going

to climb the trees on the far bank. Then it made a dogleg to the right, skittered five

feet across the surface, and sank from sight. But it came right out again in an arching

leap and headed upstream, still showing plenty of power and speed - a big, going

fish if ever there was one.

Bill McGuire was into a fish. It streaked across the pool so fast I thought it was going

to climb the trees on the far bank. Then it made a dogleg to the right, skittered five

feet across the surface, and sank from sight. But it came right out again in an arching

leap and headed upstream, still showing plenty of power and speed - a big, going

fish if ever there was one.

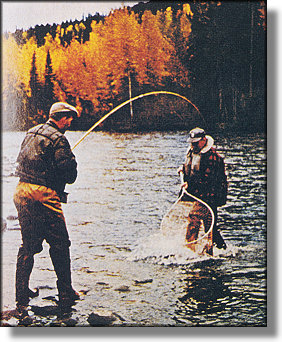

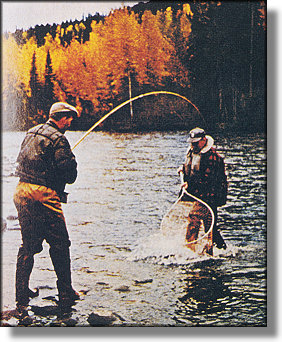

Bill reeled fast, to keep the line tight. Then the fish came to the top, slowed,

swirled, and dropped downstream, still facing into the current but slanting to the

right, and with hard sweeps of its tail gained a couple of feet.

These were rough tactics. This steelhead was hard to hold.

Then the fish surged forward a few feet. Bill swept his rod in toward our

bank, pulling the fish our way and getting it out of the current, reeled fast, and

had the trout coming. Things looked good.

But then that fighting steelhead pulled out all the reserves, shooting toward the tail

of the pool and again jumping clear. That effort tired the fish, however, and

Bill followed it downstream, easing toward the bank as he went. He got

the fish coming good and skidded it up onto the slooping beach.

"About eighteen pounds," Bill said, lifting the steelhead by the gill-cover.

"What a fish!"

That small bullet-shaped head was made for boring into heavy currents.

The body was thick, deep, and strong-looking. An overall sheen of silver

spoke of months in the sea, but the flared gill covers showed a faint blush

of crimson, and there was a crimson slash along each side from gill cover

to tail.

"He's traveled two hundred miles from the salt," Bill said. "He's beginning

to get back his rainbow colors."

Bill took the hook out and put the fish back into the river.

"Go on upstream and spawn," he said. "And thanks for the memory."

That fine fish was the heaviest of eight steelhead Bill landed that day on the

Babine River in northern British Columbia. All were taken on flies.

The steelhead, one of the greatest of all gamefish, is almost entirely confined

to the coastal water of western North America. In some places rainbows that

run upstream out of lakes to spawn are also called steelheads. But the true

owner of that name is the rainbow that goes to the salt and then comes

into coastal river.

Here is an extremely strong fish that makes amazingly long runs, breasts

mighty currents, soars up and over falls, thrashes through rocky shallows -

moving relentlessly upstream in answer to the hereditary urge to spawn

in the waters of his origin, waters that often are hundreds of miles from

the sea. A few spawning steelheads die. But many survive and work

their way back to the salt. There they fatten again in the sea's bounteous

larder and regain strength so that they can return to the river and spawn again.

From late August to mid-March (and even later in some rivers) the steelhead

hordes enter rivers all along the West Coast from California to Alaska. Like

waves beating on the shore, come the steelhead hordes. Then they hurry

upstream, heading inexorably for the spawning beds.

There are summer steelheads and winter steelheads. The summer runs occur

from late May through October, the winter runs from December or January

to about mid-March.

On the Babine River, where I watched Bill McGuire take those eight steelheads,

the best period is the last two weeks of September and all of October. But

winter comes early this far north, and icy blasts sometimes send late fishermen

out of there on the run.

Part of the thrill of steelhead fishing in the Babine is the wilderness and splendor

of that country - the dank smell of the forest, the racing rapids, the "feel" of

a land that demands the best from every men. It is stern, remote, and wonderful.

In late September and through October - at the peak of the river's steelhead run -

the landscape takes on a holiday look. The mountains shove up stands of

lodge-pole pine, whose dark green provides a rich backdrop for the flamelike

oranges of the aspens and poplars. The mountainsides appear to be dotted

with lighted candles.

All of those trees seem to rank up and march down the slopes to the lakeshores,

leaving occasional grassy, open spaces in which moose feed.

And along the shorelines you get an eyeful of rising trout.

The same rivers that harbor steelheads are also used by Pacific salmon,

which spawn there and die. In the Babine you see sockeye, humpback,

chinook, and coho salmon, all bound upstream to perform the last act

of their lives. Many of the salmon, already half dead, are blotched with

whitish fungus. Gaunt and sunken-eyed, the salmon dig out spawning

beds and go about the act of spawning.

The sockeyes are bright red along the body, with greenish head and tail.

Their beaklike mouths are studded with sharp teeth. The backs of the

males show a decided hump, another manifestation of the spawning

phenomenon.

Along the shore, spawned-out and dead fish lie rotting, and from them

rises a heavy odor. But the smell is more pungent than unpleasant, so

you soon forget it as you fish.

Perched on the fish carcasses are the everhungry gulls, mewing and

crying, pecking and pulling at the flesh. Sharing the spoils are dozens

of bald eagles, in there getting their share or perched on log jams and

trees along the river.

All are part of nature's cycle.

It is sometimes hard to get your offering to a steelhead before a salmon

or one of the river's resident rainbow or Dolly Varden trout grabs it. If

we did hook a spawning salmon, we tried to shake the hook out. If

unsuccessful, we carefully released the salmon, hoping that it would

live long enough to makes its contribution to the future of its species.

~ Joe Brooks

*Publisher's Note: The above story is by the late Joe Brooks,

written for OutdoorLife magazine in 1968. This excerpt is from

a wonderful book, The Best of OutdoorLife, One Hundred Years

of Classic Stories. We thank Cowles Creative Publishing, Inc. for use

permission. ~ dlb

|