Lesson 7 - Demon Rangeley Style

Streamers is a term applied to a great many different

styles of flies. Since it is loosely applied, we will

cover a couple styles first and return to this lesson

in the future to add new types of streamers.

The first type I will introduce you to is the Rangeley style

which was popularized by Carrie Stevens and is a distinctive

and very elegant looking pattern. They are typically tied

with four or six full feathers for wings although; some are

tied with bucktail too. These flies were designed to look

like bait fish. One wonders why a fish would mistake some

of the flies for food which often times use very bright,

bold colors. Ours is not to question why though. If they do,

that's enough for me.

These flies in smaller sizes can often be cast but, many,

if not most are trolled. However they are fished, they are

effective and worth consideration for our fly boxes.

I have found that the most difficult part of tying the

Rangeley style streamers is finding the right feathers for

the wings. Otherwise, tying these Streamers is fairly

straightforward and not too difficult. Some of the

techniques are the same with slight modifications as

techniques used in tying the full dressed Atlantic

Salmon Flies. Ribbing, full feather wings, floss, the

use of shoulders, cheeks and tinsel tags are all similar

to the Atlantics.

The typical feathers used in the Rangeley style flies are

either saddle or neck hackles. The problem with the modern

so called genetic hackles is that the feathers have an

entirely different shape than the feathers Carrie used.

The old feathers were somewhat shorter and had rounded tips.

The modern hackles have long slender feathers that tend to

be very pointed on their tips. Also, the modern saddle hackles

have very fine shafts which can be problematic when using

them for these flies. I will describe the selection process

for these feathers a little later.

Rapid River tied by Carrie Stevens

There are two fairly new books that detail Carrie Stevens'

life and flies that are worth adding to your library if you

have an interest in streamers, Forgotten Flies,

published by The Complete Sportsman that is not only a work of art, it

is a treasure trove of patterns and recipes not only of the

Carrie Steven and her works but literally hundreds of other

contemporary and older streamers. The book also covers other

styles of flies which I am sure we will highlight at more

length later in this series. This book is a must have for

Tyers of Salmon and Steelhead flies. Heck, it is a must have

just about anyone interested in flies.

Roosters Regret tied by Carrie Stevens

The other book is titled Carrie Stevens, Maker of Rangeley

Favorite Trout and Salmon Flies by Graydon Hilyard and

his son, Leslie Hilyard, published by Stackpole Books. This book

has a little more on the life of Carrie Stevens than

Forgotten Flies but, either book in your

library will give you a very good grasp of Carrie and her flies.

Royal Tiger tied by Carrie Stevens

It is interesting to note some perhaps not so minor

disagreements regarding a couple of Carrie's patterns

with one in particular being significant at least in

my view. It centers on two patterns, the Demon and the

Golden Witch Special. Forgotten Flies has

the recipe for the Demon as follows:

Demon

Tag: Flat silver tinsel.

Body: Orange silk.

Rib: Flat silver tinsel.

Throat: White bucktail (equal to length of the wing)

under which is a bunch of grizzly hackle fibers.

Wing: Six to eight strands of bronze Peacock herl

over which are four grizzly hackles.

Shoulder: Silver Pheasant body feather 1/3 the length

of the wing.

Cheeks: Jungle Cock.

Head: Black with red center band.

Source: Carrie Stevens' personal notes; private collection.

Hillyard has the Demon as follows:

Demon

Tag: Flat silver tinsel.

Body: Orange floss.

Rib: Flat silver tinsel.

Underbelly: White bucktail.

Throat: White hackle fibers.

Wing: Four to six strands of Peacock herl;

four natural grizzly hackles.

Shoulder: A Lady Amherst Pheasant tippet feather.

Cheeks: Jungle Cock.

Head: Black with orange band.

The major difference here is of course the shoulder and

throat hackle fibers color. In fact, the recipe given in

the Hilyard book is for the pattern listed in Forgotten

Flies as the Golden Witch Special. The Golden Witch

Special is not even listed in the Hilyard book.

To be honest, I chose to do the Demon as shown in Forgotten

Flies as our demonstration pattern before I got a copy of

the Hilyard book. The fly and step photos were "in the can" as

the saying goes. When I noticed this potential problem, I

contacted a few friends who have more experience in the

Rangeley style flies and asked them for some answers. There

was no clear consensus on resolving the difference in the

two books by any of them.

I also contacted Paul Schmookler, the co-author of Forgotten

Flies to see if he could shed some light on the subject.

Paul sent me a note explaining his showing the Demon and Golden

Witch Special as he did in Forgotten Flies.

Paul writes:

"The Demon, the Golden Witch and the Golden Witch Special

are three distinctly different flies, all designed by Carrie

Stevens. The Demon is a well-known pattern that has been

published many times and differs from the two GW patterns

by its cheek (silver pheasant), our dressing was verified

in the notes of the angling historian, Austin Hogan, that

are in the American Museum of Fly Fishing. There are two

Golden Witch Special flies photographed (tied with Lady

Amherst cheeks, pictured on the gatefold page 331 of FF)

that come from a private collection currently owned by

Don Palmer of the Rangeley Region Museum, formerly owned by

Marty Keane. (note: I saw these before Palmer purchased the

collection from Keane) They came in an original package,

labeled by Carrie Stevens personally...The original Golden Witch,

tied with a golden pheasant cheek, packaged in an original

celophane envelope and labeled by Carrie Stevens, is from

my own collection. Furthermore, we have over 100 additional

patterns tied by Carrie Stevens (some of which were shown on

pp 536-537 of FF), many of which share similar repetitive

characteristics to dozens of other original patterns. These

flies come from the oldest known personal collection of

Carrie Stevens and are unknown and unnamed...

I hope this has been of some help. Paul"

I then contacted Graydon Hilyard, author of the other book to

ask him for his input into this discussion. His explanation of

his rationale for crediting and attributing a pattern to the

known list of Carrie's patterns was more convincing to me so,

I will credit his listing for the Demon as the correct one.

I will leave your choice to you however. His rationale for

authenticating a Carrie Stevens fly is in his book for those

who are interested.

There are a few other differences in some of the patterns but,

they appear to be minor in comparison to the Demon and Golden

Witch Special.

In reading the Stevens chapter in Forgotten Flies,

I found several things of interest that I think you might also

find interesting. Carrie tied her early flies in a more

traditional method than she did when her tying business

grew. When she began, she mounted the wings, shoulders

and cheeks without glue. That is, like the classic Atlantic

Salmon flies were tied. At least, as the classics were tied

by most Tyers. I am sure that then, as now, there was more

glue used than will be admitted to. Later, she used cement

to stick the feathers of each side together and tied them

on as a unit. Some say that the reason she developed the

glued wings was for the action of the finished fly and

thers that this method made it easier for her production

tying. There are many current Tyers and authors who use this

method for tying the Rangeley style streamers. I would like

you to get use to tying these flies sans glue if at all

possible. This is how I will tie them in the lessons and

is how I tie them for my personal use or framing. We may

find some instance when a dab of adhesive will tame an

unruly part into submission and, we will do what we must.

My point is that I would like you to become as proficient

at tying your flies without glue as is possible. When you

have a problem mounting a part, keep at it until you either

succeed without glue or, become so despondent that suicide

seems a reasonable solution. In the case of the later,

glue is preferable! Believe me when I say that these flies

will be relatively easy to master.

Another interesting item in the Forgotten Flies

book was that in Carrie's later years, her eyesight was failing

which is not uncommon to many of us as we age, myself included.

Her late flies were apparently prone to coming apart. At least,

the wings could come undone. When we look at the construction

of these flies, we can see that the wing attachment is a

relatively small area and, if care is not exercised there

will be little to hold them on. I will address this in the

lesson in more detail. The bucktail that is often used is

another potential weak spot and deserves close attention too,

which we will do.

Whenever a group of Tyers assemble to discuss and tie historical

patterns, there will be disagreement either to dressings, methods

or, both. Such is the case regarding the Stevens' patterns and

techniques. There is a school that adheres to the practice of

tying the wings on the side of the flies almost to the exclusion

of any other method. History shows that Carrie herself changed

the way she tied her patterns as time progressed. While I don't

have a problem with tying streamers either way, I generally

prefer the top mounted wings mostly because the fly shows all

of the parts whereas the side mounted wings cover most of them

up. Rational arguments can be made for both camps as is also

the case with the argument for and against gluing the wings

together. Since I am neither a historian nor the keeper of

truth, I will let the individual decide which method suits

him/her best.

For those readers/Tyers who want more of the historical

information on this subject, I strongly suggest reading

both of these books and other writings about Carrie Stevens

and her flies so that you can better understand this somewhat

controversial subject.

With all of this in mind, I will present the Demon as our

tying example for the Rangeley style streamers.

This pattern will highlight the use of the various materials

and parts need to tie the majority of these streamers. While

the hackles used for the wings are fairly specialized, the

feathers and materials for the rest of the flies can be

almost anything you have. A huge number of feathers are

useful for shoulders, Peacock herl is in just about every

Tyer's kit and tinsel and yarn is too. Many of the flies

used silk floss for the bodies but feel free to substitute.

In fact, I find UNI-Stretch and similar materials preferable

to silk or even rayon floss on the long bodied flies. It

is easier to use, is stronger and less susceptible to fraying.

I use a material similar to UNI-Stretch that is called Woolley

Nylon and it can be found in fabric stores on large spools

for not much money. I also tend to prefer the flat UNI-Tinsel

to some of the others because it is much thicker so, it is

stronger. Being thicker and stronger, it allows you to wrap

the tinsel tighter which will keep it in place better. The

added thickness of the flat UNI-Tinsel will also stand up

to more abuse from fishes' teeth.

There is one feather that just has no substitute and of course,

I am referring to the venerable Jungle Cock (Grey Junglefowl

Gallus sonnerati). These feathers have been

used to simulate eyes on flies since the early explorers

first sent specimens back from "new" lands in Asia. Jungle

Cock has always been scarce and expensive and finding

feathers in unsplit condition was sometimes not easy to

do. We now have Jungle Cock in pretty good supply in several

grades yet, it is still on the spendy side. For flies that

are to be fished, lower grade necks may be more appropriate

while the display flies demand the highest grade possible.

The good news is that there are other feathers that can

simulate eyes although they don't look anything like the JC.

I gave some ideas along these lines in the "Cheap Atlantics"

lesson. You can also repair split JC nails with a dab of hot

glue on the back side of the nail.

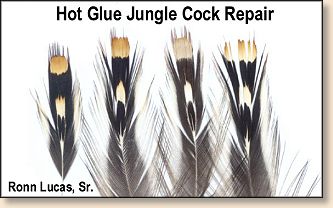

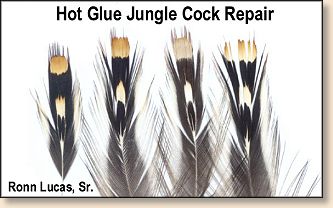

You folks who use Jungle Cock feathers on your flies have lamented the cost

as relates to un-split nails per neck and the cost of each as well. Since it

is rare to find a neck with near 100% un-splits, when one is found, the cost

is high. So we buy necks with a number of damaged feathers that increases as

the grade goes down. The options for those damaged feathers were limited to

"fishing" flies or gluing. Like you, I tried any manner of head cement,

super glue and recently, hot glue. The head cements and super glues tend to

soak through the feather and it's not difficult to tell if these methods

have been used on a fly. The hot glue is different. If you heat a flattened

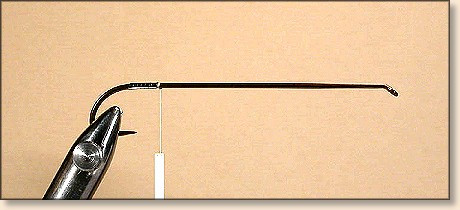

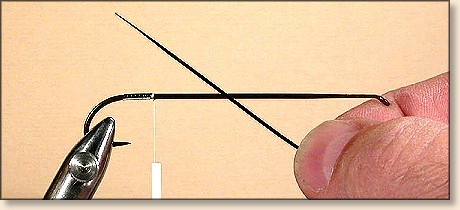

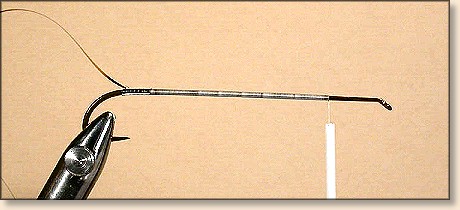

and pointed piece of wire just hot enough to pick up some glue and, transfer

this to the back of the "eye" part of the feather, you can almost not detect

a repaired feather. The important preparation is to align the feather barbs

and the "eyed" section and pinching the tip of the feather to keep it

aligned while applying the glue.

Using this method will make almost every feather on even the lowest grade

neck usable at the least great fishing flies and display flies as well.

Here is an unretouched picture of four feathers. The one on

the far left is a natural un-split feather; the one on the

far right is how the two in the center started out. The two

in the middle show the good side (left) and back (right) for a

comparison. The three tricks (that aren't hard, just important)

is to align the fibers so that all of the barbs are touching

in the "eye" area and hold them until the hot glue hardens.

The other point is the instrument to use on them. You can

either use a piece if wire that has one end flattened and

somewhat sharpened to a point. I use a Dental tool and, you

may be able to get a used one from a Dentist. The third and,

maybe most important trick is to get the glue just hot enough

to transfer some onto the wire and, then to

the back of the feather. Use a lighter to heat the glue.

If the glue is too hot, it will flow through the feather

to the good side.

If you are tying a fly for display, you might consider using

a good, unsplit nail on the front of the fly and a repaired

one on the far side. Since the fly will be in a frame, the far

side won't show.

As I said earlier, finding the right feathers for these streamers

can be somewhat difficult. I use feathers from Conranch Hackles

in Washington State for much of my general tying because their

skins are so good and the price is reasonable. I have found

some suitable feathers on their necks for these streamers.

You buy direct and I have listed them in the

Suppliers Section

of this series. Tell Denny Conrad what you are looking for

and he will try to select what you need.

His grizzly necks and saddles are some of the very best I

have seen with bright white and dark blacks.

Some of the Chinese necks and saddles can have some good

feathers. I haven't found that the upper end of the so called

genetic necks and saddles of the major brands today to be too

useful for these flies. I have some early Hoffman necks that

are good but of course, these are no longer available. Whiting

Farms is supposed to have some feathers suitable for these

streamers but, I have not used them so, cannot comment on them.

The genetic saddles that I have seen are just not suited to

these flies.

The feathers used for streamer wings should generally have

a fairly wide base with barbs in that area that are more

perpendicular than lying at a close angle to the shaft.

This will help keep and define the head area of the

streamer when in the water. The barbs should be fairly

long with medium web and have round tips. Keep in mind

that these flies are supposed to resemble forage fish.

Once you have found a neck or saddle that has feathers of

the right shape and make up, you need to pluck "matching"

feathers for your wings. By that I mean one feather from

the exact location of the other on the opposite side.

Feathers have a "spine" that is formed as the feathers

grow much like branches on a tree. The feathers, like

the branches droop on the sides. If you try to bend a

branch or feather the opposite direction of the normal

droop, it will be difficult since the structure itself

has its cell structure arranged to give strength in the

drooping attitude. What does this mean to a streamer's

wing? Take your matched pair of feathers and put them

together with the concave (under side) sides together.

Now, hold them in one hand with the feathers barbs

vertically and the shafts horizontally. Notice how much

the feathers droop and then turn the feathers the opposite

direction and compare that to the first. One attitude

should droop less than the other unless they come from

the center of the skin. It is this attitude that you want

when setting the wings.

I find it helpful to select the two or three feathers for

each side of the wing from next to each other on the neck

or saddle. If you are using strung hackles for your wings,

you will need to go through a lot of them until you find

close enough matches to make your streamer wings.

One thing that we often strive to achieve in our other tying

is small neat heads. When tying the various streamers

(Rangeley style included), the accepted norm is large heads!

Sometimes the size of the head will be influenced by the

materials used in the fly in particular the use of bucktail.

Hair generally requires more turns of thread to secure than

feathers. This is mostly true of solid hair rather than

hollow hair. In either case though, very tight turns of

the tying thread are required to make a durable fly. I

will describe how this is done when we first use hair

for our streamers.

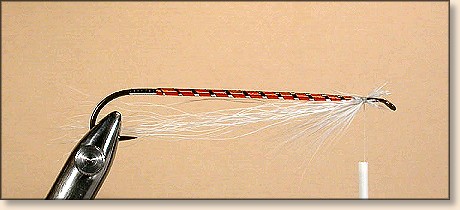

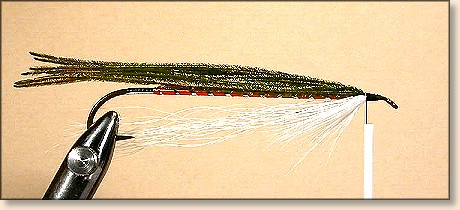

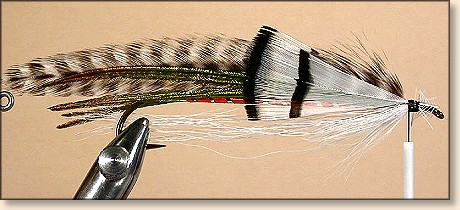

The first streamer pattern I will demonstrate is what

would be described as a combination streamer since it

uses both the full feather wing and bucktail.

Demon by Carrie Stevens - tied by Ronn Lucas, Sr.

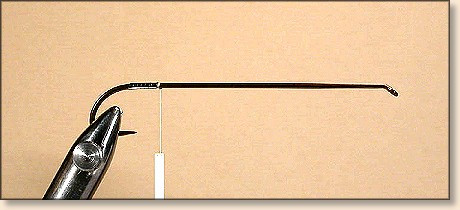

Hook: Very long shank such as the Heritage Allcock

Streamer hook or, as in this case, the Partridge CS15, Carrie

Stevens 10XL H/W Streamer

Tag: Flat UNI-Tinsel.

Body: Orange UNI-Floss.

Rib: Flat UNI-Tinsel.

Throat: White bucktail over which is a bunch

of grizzly hackle barbs.

Wing: Six to eight bronze Peacock herl over

which are four grizzly hackles.

Shoulder: Silver Pheasant feather 1/3 the wing length.

Cheeks: Jungle Cock.

Head: Black with a red stripe, Finish the head and

attach the red thread and make one whip finish prior to

applying clear head cement.

Note: The use of a black head with a red stripe in the

middle is a Carrie Stevens trade mark. This was the usual

color scheme but she did use a couple others on a few of

her patterns.

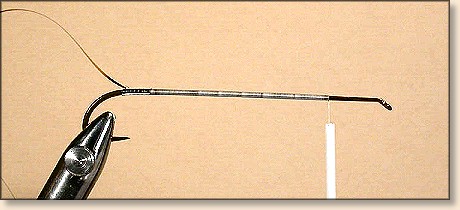

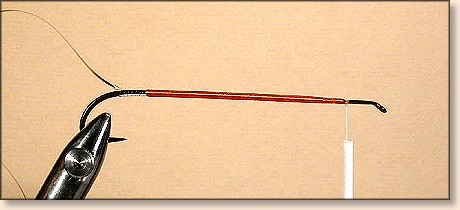

Instructions: Demon

1. Use white tying thread until the body is complete, then

change to black. Apply the tag.

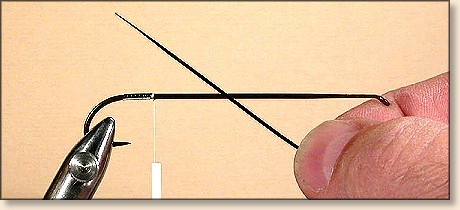

2. I like to taper the first couple of turns of the flat

tinsel just for the way it looks. I began to do this to

my ribbing after seeing the masterful work of Marcelo

Morales in Forgotten Flies.

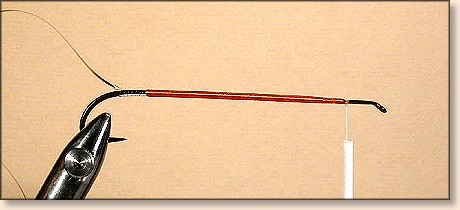

3. Attach the rib and advance the thread in flat, close

turns to the floss tie in area.

4. Attach the floss somewhat behind of where you want

the body to end. This will give you a tapered area at

the wing tie in area so there isn't a bump to kick the

wing up. With a body not using an underbody to build bulk,

this isn't quite as important but, it is a good habit to

get into. Apply the floss body and tie off & trim the waste.

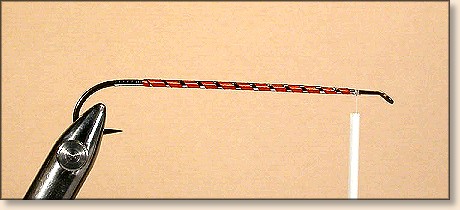

5. Apply the rib in even turns. There really isn't any set

norm for the number of turns on these flies so, use the number

that pleases your eye. I tend to go with fairly close turns to

better simulate scales on a bait fish.

6. Select a fairly small bunch of bucktail or other white

hair. You do not want to use too much hair so that it won't

foul the gape. Also, use it slightly beyond the bend. The

selection of the hair is important. The hair at the base of

the tail is hollow like it's body hair counterpart. This hair

is not what you want to use for these flies since it will flair

when tied in and this is undesirable. The hair on about the top

2/3 is solid and does not flair. Select tails that have long,

straight hair in this area for best results.

In his book, Flies, pub. by Barnes & Company, J.

Edson Leonard describes the tie in method for buck tail as

follows:

"...Construct the body according to the description

for making the feather streamer and apply the kind of hackle

you prefer. Cement the windings and, while waiting for the

cement to become tacky, snip sufficient hair to make the wing."

In this case, the throat. "...from the tail. Coat the butts of

the hair with cement and place the hair over the body after

gauging the exact location of the wing. Wind two or three loose

turns of thread over the base of the hair wing...Apply a little

more cement between the wing and body, and then draw the working

silk tight, while at the same time holding the wing between the

thumb and forefinger of the left hand. Wind the working silk

around the head until all spaces are closed..."

I do a little variation of this as follows: I stack the hair

and hold it against the fly with the tips extending slightly

beyond the bend of the hook. I then cut the butts of the hair

exactly at the tie in area so there will not be any need of

trimming waste later. I place a tiny drop of cement on the butts

which will "wick" into the hair at the tie in area. Hold the

hair with your thumb and forefinger VERY tight with the tips

of your fingers pressing the hair and body of the fly. Take

the three light turns Leonard described, pull tight and fill

the spaces with VERY tight turns all the while not releasing

the pressure of your fingers. This action will not allow the

hair to roll off the back side of the hook and it will be

exactly on top or on bottom of the fly depending on the

location you are working on. I don't bother with the second

application of cement that Leonard specified but, it certainly

couldn't hurt the durability of the fly if you choose to do so.

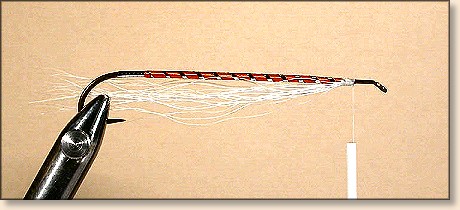

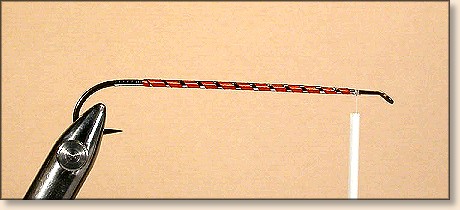

7. You can tie in the herl or the hackle barbs at this step.

I choose to tie the hackle barbs as shown. Tie in the hackle

barbs a little ahead of the tie in area for the bucktail. This

will prevent buildup in this area. Tie in the hackle barbs in

three bunches. This pic shows the bottom and far side tied in.

The sides should be tied in so they cover the tie in area of

the bucktail.

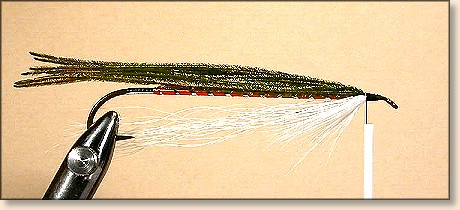

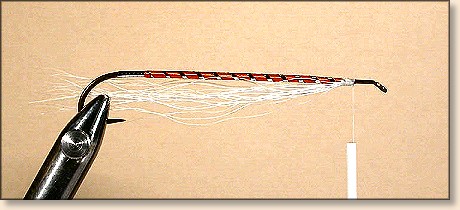

8. Hold the wing feathers up to see about how long they will

be so you can better judge how long the herl underwing should be.

9. Tie in the herl. I select the barbs and hold them together

so they are aligned and then cut them from the feather shaft.

Hold them in place while still aligned and tie in tightly as

the bucktail.

10. Hold the wing above the hook to determine the length.

This is another area where there is no clear rule. The

generally accepted norm is to have the feather wing extend

about 1/3 its length beyond the bend. This will usually keep

the wing from fouling the gape. Grasp the wing in the left

hand after you have it placed where you want it and cut all

four or six feathers at the same time. Then cut the barbs as

shown in the following illustration. Some Tyers strip the

barbs off but, I find that leaving them on top and bottom makes

a wing that is more stable and the barbs help secure the wing.

Here is a photo of the area that glue would be applied if

you were using the glued wing & shoulder method. I used black

paint to have the area show up better. Hot glue, fabric glue

or other thick adhesives work better than thin runny ones.

If you were going to apply glue to the shoulder as well as

the hackles, put glue only under the area that will be covered

by the JC eyes in case the glue runs through. I stripped off

the bases of the hackles for the photo but once glued, they

can be prepared like the cut barb and shaft method described.

Put the cement on the top of the innermost feather and place

the next one straight down onto the feather and press lightly.

Set it aside to dry and do the same for the other wing. If

you are going to glue the shoulders and sides on, repeat

the process.

Put the cement on the top of the innermost feather and place

the next one straight down onto the feather and press lightly.

Set it aside to dry and do the same for the other wing. If

you are going to glue the shoulders and sides on, repeat

the process.

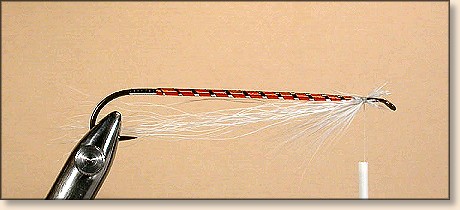

Be sure no hackle shafts are crossed when they are tied in.

Take the tying thread and make a couple turns through the cut

barbs while trying to trap the thread under as many as possible.

This will lock the wing in place much better than on a stripped

feather wing.

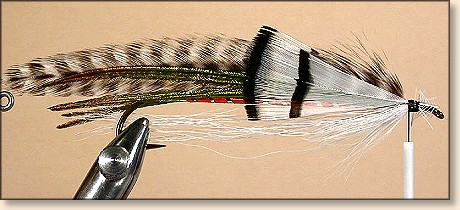

11. Select the feathers for the shoulders and trim them as

shown in the illustration below. Trimming the base of the

feather rather than stripping it will aid in setting the

feather in place and hold it better too. Tie in the feather

a little way up the untrimmed barbs as shown. Some feathers

work better than others with this method and it is generally

the feathers that have the most barbules and marrying

capabilities than weak barbed feathers which separate

when tied in. If you are using tippets for the shoulders,

you may have to flatten and/or twist the shaft so it lays

flat against the tie in area. Gluing the wings and shoulders

when using tippets can be easier.

12. Trim and tie in the cheek feathers the same way as the shoulders.

13. The finished fly.

Grey Ghost tied by Marcelo Morales

As always, I am happy to answer any questions you might have

about these patterns. You can reach me at

rlucas@cybcon.com or 503-654-0466.

Also, I will be happy to accept any flies you would like to tie

and send to me for inclusion in this series. I will need the

fly, it's recipe, any pattern info and, a short personal bio.

I will try to include every fly we get in the appropriate

section. The only limitation is that the patterns used must

be for Salmon and/or Steelhead. This includes the display

flies too.

Happy Trails! ~ Ronn Lucas, Sr.

Note: The photos of the Morales and Stevens flies by

permission of Forgotten Flies

by Paul Schmookler & Ingrid Sils.

Back to Index

|