Lesson 8 - Married Wings

Full Dress Flies

By Eric Austin

Marrying wings on wet flies and salmon flies has long

been treated by authors as a rather arcane art, one

filled with talk of barbules, rachis, barbicels and

hooklets. I hope to take some of the mystery and all

of the pseudo-science out of married wings in this

article, and give you a straightforward "how to" in

simple English, with pictures. Let's not make this

any harder than it really is.

What are we actually trying to do when we create a

married wing? We are trying to make one wing, for

either the near side or the far side of our fly, out

of slips cut from different feathers. When I say near

wing, I mean the one closest to the tier. For instance,

here is a piece cut from the left side of a turkey tail

feather that could be used as the near wing in a wet fly:

Here is that same turkey tail piece, married with a

couple of strips from the left side of a piece of

Amherst pheasant tail:

What did I do to combine these? I added the top strip

of Amherst pheasant to the turkey first, pushing the

edges of the feathers together starting from the tips.

When the feathers were together somewhat I then grasped

the butts in my right hand, and "zipped" the feathers

together with my left middle finger and thumb. The bottom

strip was then added the same way. There really is nothing

to it, these feathers WANT to marry, they HAVE to marry or

the bird couldn't fly. We don't actually care why this is,

just accept the fact that it is. But there are some hard

and fast rules that must be followed, or this marriage

will end in a quick divorce.

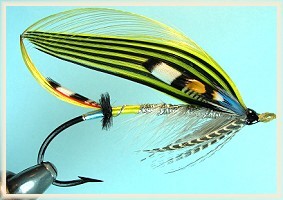

Let's look at a real-world example and I'll explain the

rules. We're going to tie a Ray Meade, a full dress salmon

fly that has wings with black and yellow stripes, and we're

going to do the married wing first. What I'm going to do

initially is lay out my feathers, getting my lefts and

rights together and straight so I don't get them mixed up.

Take a careful look at this picture:

These are quasi "matched pairs" of feathers. We hope that

the feathers you use will be truly matched, one from each

side of the bird. As I look down at the top of these

feathers, you'll notice that the ones on the left curve

slightly to the right, and the ones on the right curve

slightly to the left. It's not extremely important that

your feathers do this, but it is a good way of keeping

your pairs straight. We will marry slips cut from the

left side of the left hand feathers together to make the

near wing, and then later, we will marry slips cut from

the right side of the right hand feathers to make the far

wing. Don't get these mixed up! Do one wing at a time,

and put the other feathers aside. Here's a diagram showing

you what parts of what feathers to use, for which wing:

We are looking down on the top of the feathers, in other

words at the convex side if they are goose shoulders,

with the stem toward us. On some feathers it's no so

easy to tell which side is the "top." Look for a

single stem, if the stem seems to have two sections

to it, you're looking at the bottom of the feather.

Orient your feathers this way every time. We are going

to make the near wing first, so we will use only the

two feathers on the left in our picture. Put the other

two feathers away. It's a good idea to wash dirty feathers

in Woolite, slowly dry them, and then steam them. They

will marry more easily. Prep the feathers, getting rid

of the bottom third of the fibers or so, which is just

fluff that will never marry anyway. Cut a strip three

strands wide from each feather. It will look like this:

Now cut three more from each feather, and lay them out

in order, just as they came off from bottom to top.

If any of the slips you cut is damaged or has intertwined

strands, discard it and cut another. You really need decent

slips to work with, or you have no chance. You may trim the

odd fiber sticking out of the tip, I won't tell. I've just

married these strips myself, starting with black on the

bottom, adding a strip at a time, going up. I found that

I hold the base strip in the middle of the strip with

the thumb and middle finger of my left hand, I then

take the strip I want to add with my right and match

its tip to the one I'm going to marry to (the one or

ones in my left hand ). I then pinch both with my left

hand, keeping them together, and push everything else

together with my right. Then I grab the butts of all

with my right, and "zip" with my left thumb and middle

finger, causing the feathers to marry completely. Be

careful when you're marrying strips to not get a strip

flipped over. The curvature of the strip you're marrying

must match the ones you've already done, or it won't marry.

I like to stagger the slips slightly as I go up, so that

the resulting wing has a curvature similar to that of a

section of a feather. Lots of tiers do it this way, but

Ron Alcott likes to make all the tips even. Am I going to

argue with Ron Alcott? I think not. Do what you prefer.

When all is said and done it should look something like

this:

Boy that was easy. What could possibly go wrong here? Well,

lots of things could go wrong actually. I've already talked

about a strip getting "flipped", it'll never marry. To avoid

this happening you could cut a strip at a time from your

feathers, instead of cutting them all at once as I've done.

It might be a good idea to do them this way at first, so

you're less likely to flip a strip. You can actually get

a feather sometimes which is of such poor quality that it

won't even marry well to itself. Forget about that one,

even if you get it to marry, when you tie it in the wing

will fall apart. Make sure you've prepped your feathers,

washed them in Woolite, gently dried them, and then steamed

them. This will greatly help the ability of these feathers

to marry, especially if they're from the dreaded golden

pheasant tail. Some feathers are just tough to marry period,

and two that leap to mind are macaw and golden pheasant tail.

Of course, if you didn't follow my instructions and are

trying to marry lefts to rights, you're doomed. One other

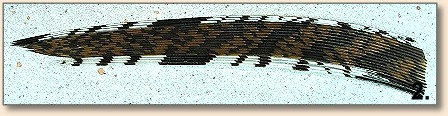

thing can happen, and you really need to watch for this.

Look out for "reverse curl" in your feather. You see a

lot of this with turkey. It's where the tips of the

feathers curl back up toward you as you look down on

the top of the feather. Here's a shot of a turkey tail

feather where the left side of the feather exhibits lots

of reverse curl.

Mallard primaries do this naturally, as do goose primaries.

It can be very frustrating to try to marry a left that has

a ton of reverse curl to a left that doesn't. It can be

done, but it might be best to try and straighten the feather

out first. If it's goose or swan, you can iron out the

reverse curl with an iron on very low heat with steam.

If it's turkey, you can't. With turkey you can wet the

feather and put the side of the feather where you want

less curl in between the pages of a book, then stack

more books on it. In about a month you should have a

usable feather. I don't go through these contortions

myself; I buy more feathers. That fits in with my life's

plan of spending every available financial resource at

my disposal on fly tying materials.

Can you marry lefts that have a lot of reverse curl to

other lefts that have a lot of reverse curl? Yes, no

problem. The Ray Meade shown at the top of the article

was done that way. I had yellow and black swan feathers

where the long sides had lots of reverse curl, so I went

ahead and used them. Tying them in was a bit more difficult

though than if I had been able to use the sides of the

feathers without the reverse curl. Of course, those sides

were too short.

So we've got our left wing completed, and now need to do

the right. In order that your marrying technique stays

consistent, it is a good idea to orient the feathers

with the concave or bottom sides up, so that the slips

you are going to cut, while still being rights, are

available to you on the left. It's just easier to cut

them off if you're right handed. So you'll start with

the feathers like this:

Now cut slips like this:

Marry them, keeping the concave or bottom sides of the

slips facing you, just as you would look at the far

wing on a fly if you tied it in alone. Again, start

with black on the bottom. It should wind up looking

like this:

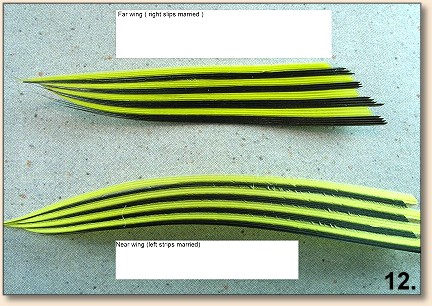

Here are both married wings, ready to tie in:

You'll notice that the right wing (far) is shorter

than the left. That's because my right feathers

didn't have enough strand length. It's a good idea

to measure your feathers for strand length before

you start. Measure your hook shank all the way to

the bend of the hook, then add ¼" or so, and try

to get feathers with strands that are at least as

long as the total. For instance, if I'm going to

tie a 3/0 fly, and the shank length is 2", I'll

need at least 2 and ¼" strand length on all my

feathers. You will spend your life trying to find

feathers with enough strand length.

Marrying Single Strands

Marrying single strands might seem difficult at first,

but there's a trick. Marry two or more strands of a

feather in, then cull out everything but one strand

with a bodkin or your scissors. If you plan correctly,

you can then take the fibers that were culled out and

use them as a group later. Let's say I want to marry

two strands of yellow, then one of red, then two strands

of yellow, then two of red. I'll start with three strands

of red, marry it to the two of yellow, cull out the extra

two strands of red, saving it for the two strands of red

needed later. Not so hard after all.

Married Wings - Wet Flies

Marrying wings on wet flies can be a little confusing.

You are generally using mallard quills here, as is

traditional. You can use goose shoulders, but it's

really not done much, and tends to get a little "wimpy."

Mallard quill has a lot of reverse curl in the feathers,

and because of that, if you use the techniques described

above, lefts for near wings, rights for far, you will

wind up with wings that have their tips out, pointing

away from each other, like this:

How big a problem is this really? Not a problem at all,

J. Edson Leonard liked his wet flies this way, and none

other than the great Pennsylvania tier Don Bastian agrees,

and now ties all his wet flies in this manner. It's great

because you don't have to do anything differently; the

wings are married and tied on just as you would full

dress wings, but now the tips point out due to the

reverse curl of the mallard quills. The "good" side

of the feather shows on the outside of the wing with

this method. Now let me throw in the monkey wrench. I

personally don't tie my wet flies this way. One look at

Trout by Ray Bergman will make my point.

The flies I remember from the '60s didn't have their

tips out, nor do the ones in Trout. But

there is more than one way to skin a cat, and Don's way

is certainly easier, and his results speak for themselves.

If you'd rather get the "tips together" look, it's easily

done. Once you've married the wings simply tie the "right"

married feather in on the side toward you, and the "left"

on the side away from you. In other words, reverse the

left and right wings. Note that the "good" side of the

feathers is now not showing. Now your fly will look like

this:

However you do it, marrying wings on wet flies is a

great way to get your feet wet with marrying wings

in general. You're typically marrying only three

slips, and if you use Don's method (tips out), it

will lead directly toward full dress salmon fly wings.

So I wholeheartedly recommend starting your marrying

career doing some wet flies tips out, then moving on

to full dress flies once you've gotten things down.

Some Conclusions

Marrying wings is either the easiest thing in the world,

or the hardest depending on two factors. The first is

your materials. Are they clean, steamed, fresh, undamaged,

high quality matched pairs of feathers? Are these feathers

free from a lot of reverse curl? Is their curvature

generally the same? Are you cutting slips from the good

area of these feathers (the middle third or slightly above)?

The second factor is you. Have you gotten things laid out

and prepped properly? Have you measured the strand length

on your feathers? Are you working with just one group of

feathers at a time (lefts or rights)? You haven't mixed up

the rights and lefts have you? This is the kiss of death.

You will NEVER marry a right to a left. Am I marrying good

side to good side with my slips? In other words, do the

curvatures of the slips I'm trying to marry match? If one

gets flipped, you've got a problem. Are you working hard

enough to get these things together? Manhandle these puppies.

MAKE them go together. If you've done everything right, and

they still won't marry solidly, throw one or more slips away.

Try another feather. Don't take no for an answer. I like to

swear at the feathers, but that may not be for everyone.

Just keep in mind that it's natural for these fibers to

want to marry, and chances are good that if they're not,

it's your fault. Above all, have fun. ~ Eric Austin

Back to Index

|