With the flowering of the British Empire also came some very

wealthy men with little or nothing to do. They turned to all

manner of interests to occupy their time, naturalism, chemistry,

exploration, religion, and art and field sports. Suddenly

fishing became one of the things to do! Tackle developed apace.

Advances in rods, reels (or winches) lines and our immediate

interest, flies.

Early salmon flies were merely big trout flies, on the premise

that bigger quarry needed bigger baits. These were fairly

rudimentary examples of what we now consider to be an art, just

wool bodies and feather wings, of convenient materials and rustic

colours. Eyes had not been developed on hooks, so gut loops were

whipped on the tapered shank as the first step in tying. However,

as a distant portent of things to come, grub patterns were also

used, probably as food imitations.

It was believed at that time that salmon ate butterflies, and

you can see where this is leading!

It seemed to follow in those days that as salmon fishing became

popular and was to be found at its best in the rivers flowing

through lordly estates, that the gentry would take up this new

sport with enthusiasm. They had the time, the money and above

all, the rivers.

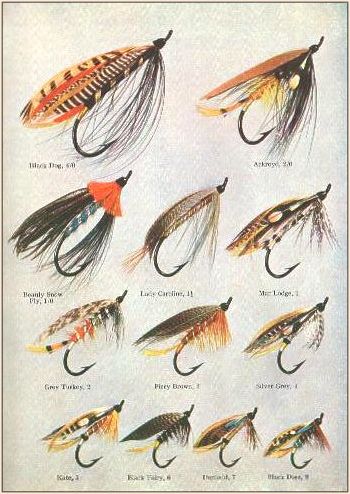

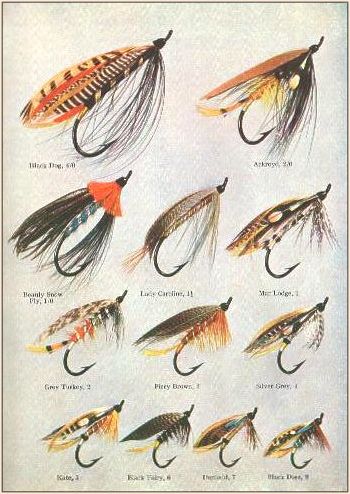

The fact that salmon flies became the gaudy somewhat over-the-top

objets d'art that they did owes a lot to the fact that a rich man

fishing for the king of fish would feel it only fitting that he

should fish with a richly dressed and expensive fly. It was found

that these caught fish better than did their predecessors and so

the process started.

I have a book that I treasure greatly, How to Tie Salmon Flies

by Captain Hale. A classic, printed in 1892, it shows how the salmon

fly had reached a peak of opulent development, (or should we say

absurdity?) I know that eyebrows will be raised at my temerity

in using that word, but I really cannot feel that the salmon,

for whose benefit these gorgeous creations were intended, was

interested in or capable of discerning the myriad colours and

subtle shades deemed so essential at that time.

Consider, if you will, the dressing the worthy Captain Hale gives

us for the Jock Scott:

Tag: Silver twist and light yellow floss.

Tail: A topping and Indian crow.

Butt: Black herl.

Body: In two equal sections; the first, light yellow

flossed, ribbed with fine silver tinsel; above and below are placed

three or more toucan, according to the size of hook, extending

slightly beyond the butt, and followed by three or more turns of

black herl; the second half black silk, with a natural black hackle

down it, and ribbed with silver lace and silver tinsel.

Throat: Gallina.

Wings: Two strips of black turkey, with white tips

below; two strips of bustard and grey mallard, with strips of golden

pheasant tail, peacock sword feather, red macaw, and blue and yellow

dyed swan over, with two strips of mallard, and a topping above.

Sides: Jungle cock.

Cheeks: Chatterer.

Horns: Blue macaw.

Head: Black.

Tied on the size of hook prevalent at the time this was a serious

piece of work, not something you could run up on the tail of a

pick-up in response to a sudden hatch, but that a salmon could

discern those features which make a Jock Scott differ from, say,

a Silver Grey or a Black Rover, both flies of similar outline and

overall colour, is really beyond the realms of likelihood. Add to

this the fact that lists were drawn up, in all seriousness, of

which flies one was to use in various rivers, with the inbuilt

suggestion that salmon would refuse a fly lacking any of those

features deemed by the pundits to be essential for its own river!

On the Welsh Dee one was to choose from the following list: Jock Scott,

Butcher, Wilkinson, Black Doctor, Gordon or Grey Turkey.

On the Lancashire Lune however, a river not a million miles

away, emptying into the same bay of the Irish sea though its

drainage area is vastly different, one was almost commanded

to pick a fly from: Grey, Childers, Blue Doctor, Parson, Jock

Scott. The Wye was very different. It required a Sun Fly,

Colonel, Britannia, Black Dog or the ubiquitous Jock Scott.

The Tyne and the Tees in north-eastern England had to have

totally different flies in spite of being no more than thirty

miles apart.

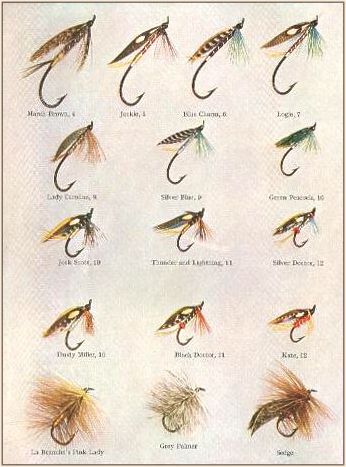

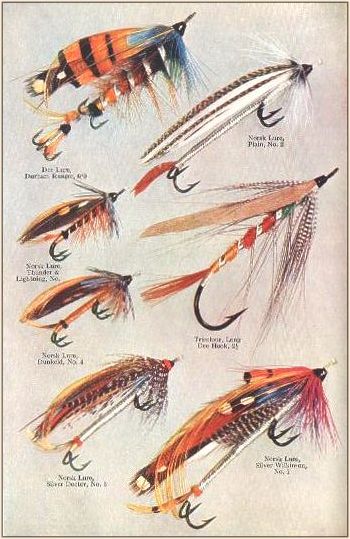

Into this long-established routine, in the 50's, dropped a

revolution in pattern, size and more importantly in fly

construction. To say nothing of the hook.

We had, from time immemorial, sold Best Quality salmon flies

tied on black japanned, return shank, up-eyed hooks of a distinctly

Kirby bend, together with Second Quality flies, a much more

plebeian offering. These were more simply dressed, the expensive

exotic feathers being omitted, and tied on a plain down-eyed

bronzed Limerick hook, The fact that these would have tempted

salmon just as efficiently as their esteemed brethren never

seemed to come to light. The best people with more time to

fish the best waters naturally caught more fish. They also

used the best flies (they cost more so they must be better-nothing

changes!) therefore they perpetuated the myth that these complex

monstrosities were necessary in order to catch salmon.

Works of art they may have been, but their end was in sight.

A.H.E.Wood had brought about the first stirrings of revolution

with his theory of low water flies fished shallow on a greased

line. Anglers soon found that Wood's small, lightly dressed flies

took fish in normal and even in higher than normal water.

Smaller flies were on the way.

|