|

The window I'd cracked open the night before was letting in some

great-feeling cool morning air. I could have laid there dozing

another hour, maybe two hours, but suddenly sat up with a start,

trying to remember something.

Was it four days ago I checked the Kansas City District Corps of

Engineers Lake Forecast web site to ascertain outflows and

projected outflows at some of my area's federal lakes? One lake

relatively close reservoir, Pomona Lake, was releasing 250 cubic

feet per second (cfs) but the lake forecast said that three days

hence its volume would be cut to 100 cfs.

"Three days hence" was...today! And it's dawn and what am I doing

in bed? Throw on some rags, hop in the pickup, get down to Pomona

and try that outlet pool! Get movin', boy!

An hour later I parked next to the outlet conduit. Two fishermen

were already there, both devotees of the angling technique most

often seen at this outlet: you reach over the stout chain link

fence mounted atop the outlet chute's concrete wall, lower a

baited hook and heavy sinker straight down 20 feet into the

stilling basin then stand there waiting for a bite.

Neither of these fine gentlemen would be snagging me with false casts

propelled by a Spey rod. They in turn had no cause to fear getting

snagged in the ear by one of my false casts, as I was intent on

fishing the large pool 40 yards downstream from their concrete-walled

"wishing well."

At Pomona Lake's outlet a man-made riffle separates the stilling

basin from the pool I would be fishing. The pool below this riffle

is where one morning this spring I caught and released 125 small

crappies.

The federal dams in Kansas generally aren't opened for large volume

releases unless the lake's watershed has received heavy rain or snow

melt runoff during the preceding weeks. Heavy surface runoff carries

lots of sediment into the lakes, making the water turbid. The water

at Pomona outlet today was quite dingy. Nothing startling about this

and I was unconcerned because on many previous trips here I'd caught

fish despite this handicap.

I began working an eddy below the riffle and in short order a crappie

fell prey to my best good buddy – "Old Reliable," a #10 flashback

Hare's Ear Nymph. Ahh...this was going to be a good trip and I was

ready for one. In my pickup's bed sat a Styrofoam cooler containing

a bag of ice meant for keeping fish cold and fresh during the drive

home. I'd also brought a floating fish basket with which to keep alive

the crappies I caught until such time as it became necessary to tote

my haul up to the pickup and place them under ice.

Meat fishing; yes, I was meat fishing, hoping to load up on great-tasting

crappie fillets. Catching one so quickly therefore had me feeling excited.

Thirty minutes later I was still somewhat excited but becoming confused:

not another fish of any kind had touched Old Reliable. Then I snagged

the bottom and had to break him off.

Since I was trying for crappies only and the recent 250-cfs release

had doubtless flushed many crappies from the lake's main body into

this pool, some of those recent arrivals had to still be holding here.

I looked inside my fly box for a pattern specifically designed for

catching crappies. There it was: a Crappie Candy. (My success in

making conceptual links such as this often zip past me, not coming

to mind until long after I've left the water.)

On its first presentation, an actual crappie grabbed the crappie fly

called Crappie Candy. What a deal; I'd connected the dots! My excitement

level came rushing back. Then twenty minutes ticked away without another

touch and confusion took excitement's place. I was debating whether to

switch flies again when the rock-lined bottom of the outlet pool decided

the matter for me by grabbing Candy at a depth and distance from shore

that kept me from wiggling it free. I had to break off the fly.

Okay, what next? Let's see: there's a #12 Skip Morris Panfish that's

been in my box for ages. It's mostly red in color and I hardly ever

use red flies, but...why not? Into the pool it flew. Two freshwater

drums, a channel catfish "fiddler" and a crappie liked it. Then

another rock grabbed hold, wouldn't let go and I had to break off

Skip Morris, too.

On went a #10 beadhead Olive Woolly Bugger with red marabou tail.

By now I'd worked my way far down the right bank. Two crappies

fell prey to the Bugger, both hookups happening close against the

rocky shoreline. Then the action fizzled. This might be one of

those days where a person is lucky to catch one or two fish per

pattern used. I methodically backtracked to the riffle where I'd

started from, catching nothing on the way back. But at least I

didn't lost the Bugger and by now that felt like a minor triumph.

My eyes were sore from squinting into surface glare (I'd forgotten

to bring my polarized clip-ons). I was hungry from skipping breakfast

and I was thirsty. It was 11AM, long past time to skedaddle from this

slow-action place. But then I looked at the stilling basin upstream

of the riffle, at deeper water I hadn't thrown a single cast into all

morning and shrugged, "Why not? I'm here."

I crept to a spot on the rocks twenty feet above the riffle and sent

a cast straight out. My intention was to let the Woolly Bugger sink

for a few seconds and then retrieve it more or less parallel to the

riffle's upstream zone where water is just beginning to enter the rocks?

Each cast thus thrown would take a curving course back toward me due

to the cross-current. By manipulating the speed of my retrieves,

changing the number of sink-seconds I gave each Woolly Bugger after

splashdown and by landing the Bugger closer to or farther from the

riffle I could methodically explore almost the entire linear zone

along the riffle's head.

This business of systematically probing the head of a riffle is nothing

I dreamed up. It's a tactic I saw demonstrated some years ago during

an episode of In-Fisherman on TV. That broadcast stuck in my

mind, stuck to the point where during canoe trips on Missouri's Current

River I made it a habit, whenever approaching a riffle or rapid, to

peer down through the clear water and observe the aquatic environment

passing below.

Sure enough: fish do congregate at the heads of riffles. They do

it because the rising riverbed compresses the habitat through which

approaching prey items must swim. The confined area makes it easier

for predators to spot and grab prey.

Fine, but right now I'm not fishing the Current River or any other

beautiful clear water stream. This is the stilling basin of a muddy

Kansas lake and I'm tossing a fly of muted color into stained water

above a man-made riffle. Picture postcard material this place ain't,

but it does let me practice head-of-riffle angling in case I'm ever

in southeast Missouri or northern Arkansas trying for...

My Woolly Bugger dimpled the water, drifted five feet toward the

riffle and got pulverized by a fish that zoomed upstream so fast

I thought it was might swim through the outlet's conduit pipe and

escape back into the lake.

A few minutes later I led the fish into the rocks at my feet,

grabbed its lower jaw and lifted it for identification. Two

small rough patches arranged side-by-side on its tongue make

it a wiper (white bass/striped bass hybrid). Well, I'll be!

After releasing it I cast back into the same general area, maybe

ten feet closer to where I was standing. I let the Woolly Bugger

sink a couple of seconds then began another retrieve. Crunch!

Another hard hit followed by another wiper brought to hand after

some difficulty.

What's going on here? Hey, this is cool!

A double-haul cast airmailed the Bugger three-quarters of the way

across the stilling basin. Not by aim but accident it landed much

closer to the riffle's front, where the shallowing bottom was causing

the squeezed current to pick up speed. The Bugger had barely hit

the water when a swirl appeared and it was violently inhaled by

what turned out to be yet another wiper!

At this third hard strike I involuntarily let out a loud whoop.

I began visualizing a row of wipers spaced along the riffle's

leading edge like defensive linemen at a football game's line

of scrimmage, each fish hunkered down facing into the current

on hair trigger alert for prey sneaking through into the pool

below, each wiper motivated by predatory instinct to uphold the

defensive lineman's creed: "They Shall Not Pass."

Until now I'd ignored the water closest to me, always casting

farther out. The untried water was structurally identical to

what I'd just caught three fish out of. Why was I avoiding it?

I don't know; why do we always overlook the water close to our

shoes? No "casting drama" maybe? Trying it would involve throwing

the Bugger all of twenty feet – essentially my rod's 9-foot length

plus the tapered leader and some change. Boring but, oh, alright...

I let the OWB settle out of sight. It was drifting toward the

riffle on a gradual up-angle rise when Thunder Fin took note and

attacked with extreme prejudice. If this wasn't the stilling basin's

Alpha wiper I'll eat your hat. He fought harder than the first three

wipers combined, running me around the stilling basin like I was a

puppy on a leash before punching my ticket in a most humbling fashion.

At my feet was a triangle of large rocks that formed a "harbor" into

which I'd led the first three wipers before lipping and unhooking them.

Beside these three rocks floated my fish basket with four crappies

inside. The basket's nylon cord was not connected to anything; I'd

simply swung the basket into the pool then draped the cord across some

rocks. No need to secure the cord because an eddy current was pushing

the basket firmly against the bank.

When he finally showed signs of being whipped, I gave Thunder Fin a

steady pull and slid him into Catch and Release Harbor. He entered

innocently enough but suddenly zipped around one of the three rocks

and bolted for the open, in the process swimming under my fish basket's

cord so fast that the cord twirled itself around my leader. The result

being, Thunder Fin was now towing my fish basket behind him.

Not wanting to lose those four crappies, I quickly bent down to rescue

the fish basket. This sudden move triggered a painful cramp in my left

ribcage. As I was trying to relax the cramp my leader pulled free of the

fish basket's cord. Then, instead of racing away into the stilling basin's

depths, the fish turned hard right and charged into the riffle, swimming so

fast he literally ran aground and flopped onto his side.

I was forced to choose between saving the fish basket (now beginning

to drift downriver), or hobbling over to pounce on Thunder Fin before

he could get his wits about him. I opted for the fish basket. It was

risky reaching for it because the bank here drops away sharply. I had

on street shoes and if I slipped on these wet rocks I could fall into

the stilling basin.

Extending my left arm as far as I could, my fingertips just barely touched

the fish basket's wire handle. I leaned out a little farther, slipped on a

wet rock and fell into the stilling basin.

Cursing and dragging the fish basket ashore, I rudely dropped it on

the rocks and turned my wrath downriver. The rib cramp was still

hurting and I didn't exactly appreciate this recalcitrant wiper

making me look like a fire-hosed circus clown.

And of course, no sooner did I lay down my fly rod and stand to go

fetch him than Thunder Fin wiggled down between two rocks and found

barely enough water depth to offer traction. Before I could reach

him, with a head shake he dislodged the barbless Woolly Bugger. Then

a second vigorous spasm propelled him back into the stilling basin.

It happened fast but I think he flipped the middle spine in his dorsal

fin at me as he rocketed past.

I interpreted this fiasco as a sign that it was time to call it a day.

I held the fish basket out over the water, pushed inward on its lower

trapdoor and shook out the four crappies. One by one they splashed

into the stilling basin, lingered a few moments then turned for the

depths and swam home. I climbed the rocks, got in my pickup and

drove home. Everybody went home.

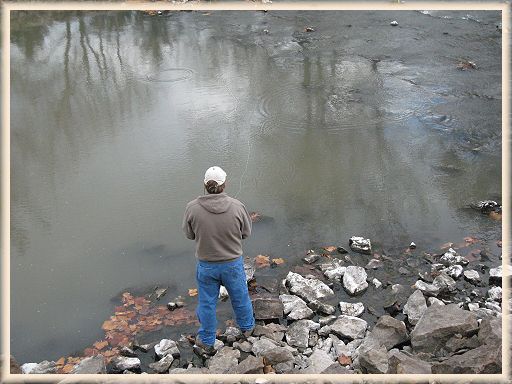

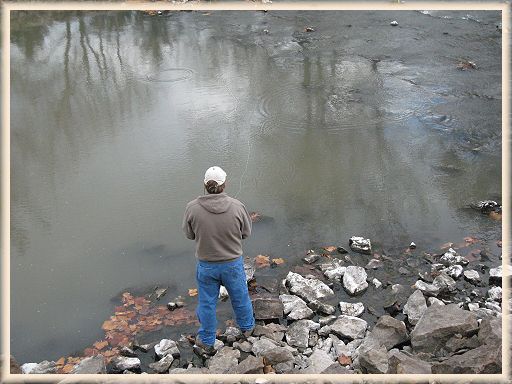

THREE WEEKS LATER I returned, this time with backup. The second

visit happened because Spring Hill, KS fly angler Tim Giger invited

me to try for white bass with him at another reservoir, Melvern Lake,

not far south of Pomona. At Melvern that morning Tim and I dealt with

high wind from the south – a wind that created good conditions for white

bass fishing off the north shore but at the cost of grinding us down

physically from our struggles casting into it.

When time came to leave Melvern Lake I suggested a highway route that

would take us past the aforementioned Pomona Lake. Pomona dam's outlet

is bordered closely on the south by a tall hill that might shield us

from the wind.

We slowed on approaching the outlet's parking area. From the roadway

I glanced down over the guardrail in time to see something totally

unexpected: a few feet upstream of the riffle a fish had just swirled

to the top, leaving an expanding concentric ring smack dab in the zone

where I'd caught those four wipers three weeks earlier.

Surely those wipers aren't still here, I thought. Or maybe they are?

I would leave it to Tim to find out. He'd already told me that he has

fished this place before, so when I clued him to the rise that I'd seen

he knew just what to do and how to do it.

Tim worked the riffle's up-zone using a Gummy Minnow, a most interesting

streamer pattern due to its virtually transparent rubber body. After

only a few casts, something big and mean decided it wanted Gummy in

its tummy. Weakened finally after running a number of hot laps around

the stilling basin perimeter, the fish surrendered and got lifted for a

mug shot.

Results from the finprints we inked aren't back yet from the FBI

so I can't claim a positive identification; still, I'm 99% certain

the fish Tim is holding below is none other than Thunder Fin.

I felt vindicated seeing this ferocious beast briefly held up in

the air. And I felt better yet watching Tim cut him loose with

just a warning ticket. Thunder Fin is right back out there on

the battle line, him and his speed demon buddies. (Tim caught

and released the other three, too!) Their attitude is bad.

Real bad. But they work their territory, we work ours and

maybe we'll all meet up again. ~ Joe

About Joe:

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

Joe at one time was a freelance photojournalist who wrote the

Sunday Outdoors column for his city newspaper. Outdoor

sports, writing and music have never earned him any money,

but remain priceless activities essential to surviving the

former 'day job.'

|

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.