|

As a rule, the fly fishing I do from my canoe is a shallow

water affair. To me this is only practical: with the lone

exception of the white crappie, the panfish group that

resides in Kansas inhabits water less than 10 feet deep

for more hours of the day, more days of the year, than it

occupies water deeper than 10 feet.

I own an electronic fish finder (a portable unit) whose

transducer shoots an ultrasonic beam that measures

15-degrees in angular width. Not every buyer of fish

finders considers the real-world implications of transducer

search beam width; I didn't before buying my unit.

One day I wanted to see a concrete representation of my

unit's search cone. Grabbing a protractor, pencil, blank

sheet of graph paper and straight edge I lined out the

maximum underwater area that my fish finder "sees" at

various water depths. The result was startling: my unit's

15-degree search cone looks at a circle of water so small

in circumference that the image appearing on my unit's LCD

screen is largely useless as a means of seeing fish in the water

beneath and around my canoe.

Electronic fish finders are fascinating instruments nevertheless,

and my drawing did nothing to diminish my appreciation for the

unit's ability to perform three important and useful tasks: 1) Tell

me how deep the water is; 2) Show me the changes in water

depth as my canoe moves about from spot to spot, and; 3) Show

me underwater objects around which fish often spend time.

I therefore rigged my canoe with my fish finder and launched

on the same 4-acre pond where recently I caught a 13-inch

black crappie – a slab that set my heart a-racing. My fish

finder quickly revealed a large area of impressive but uniform

depth – the excavation zone where enough cubic yards of soil

mass had been bulldozed to construct the pond's massive dam?

But nowhere in this flat, deepwater zone did I spot any of the

classic structures you hope for: drop-offs along creek channels,

submerged brush piles, etc. And numerous crossings of the

pond's main body detected just one cluster of "vertically stacked"

fish that may have been a school of crappies. (The fish icons

moving slowly across my display screen were so tiny they

suggested a pod of bluegills, not suspended crappies.)

After five hours I stopped trying to find fish in deep water.

Either I was missing them or they simply weren't there. That

I could tell, the deep water area was virtually deserted.

According to the landowner, white and black crappies were

stocked here initially. But I wonder if this pond no longer supports

a meaningful population of whites. It does have plenty of blacks,

though. I have a theory to explain this.

Black crappies, I've read, instinctively pursue a solitary,

stay-at-home, shallow water lifestyle that lets them thrive

in the weedy shoreline habitats typical of this and most

other Kansas farm ponds. Whereas a white crappie thrives

when it can operate as part of a school that roams large

open water areas such as those found in state and federal

lakes.

It didn't dawn on me until two days after this trip that

the only crappies I've ever caught in this pond are blacks

that took my fly fairly close to shore. I had used my fish

finder, then, in a manner better suited to locating white

crappie schools occupying deep water. My failure to

find any schools of suspended fish was not the pond's

fault, nor an indication of my fish finder's technological

failings. Rather, I was wrong in examining this pond

without taking into account the lifestyle differences

between black and white crappies. My sonar investigation

looked at water almost 20-feet deep – excellent habitat for

a kind of crappie unlike the kind I know for a fact lives in

this pond.

So my entire day was wasted pursuing a lost cause, right?

Well, not exactly. For one thing, not finding any schools of

fish in deep water lets me abandon an idea I've harbored for

quite some time; namely, that I should outfit both my anchors

with longer lines so that I can fish this pond's main area. No

more am I interested in the pond's deep water; my future

crappie-catching efforts will now target the shoreline zone.

There'll be no more nagging thoughts that I'm missing out

on something wonderful by not trying the deep water. This

is where purchasing even the least expensive electronic fish

finder is money well spent.

For another thing, while looking for suspended deep water

crappies I caught three nice bluegills that were occupying

water less than 10 feet deep. How that happened was I

repeatedly paddled or drifted across the pond's deep main

area conducting sonar passes, and upon reaching shallower

water I would anchor and fish the weedline for fifteen or

twenty minutes before searching deep water again by

crossing the pond on a different compass heading.

But during my first five hours on the pond even those

weedline areas were slow going – just three bluegills

were caught. Again this was my fault, not the pond's:

I'd arrived that morning grimly determined to find and

then catch suspended deep water crappies and I didn't

care if it took me all day to do it. With that stubborn mindset,

I stuck with fly patterns more attractive to minnow-eating

crappies than insect-eating bluegills.

So really, this trip came close to getting written up as an

object lesson in, "How empty your fish basket can be on

afternoon drives home if your brain leaves town that

morning filled with pre-conceived ideas about how the

day will turn out." Only a combination of failure, curiosity

and the generosity of an FAOL member spared me from

that sad reporting task.

Five hours of steady casting and my minnow and large

insect imitators were being ignored. Even my oldest and

most reliable #10 nymph was attracting scant attention.

The time finally came to make a radical change. Okay,

fine, but change to what? I'd spotted no surface feeding

action all day, so while cabbaging anew through my fly box

I bypassed the dry flies and poppers and looked at a row

of small furry jobs for something, anything, that might produce.

Here is where I recalled some stories I've read in the past,

stories that told how fish inhabiting relatively clear water will

sometimes prefer small, dark-colored subsurface patterns?

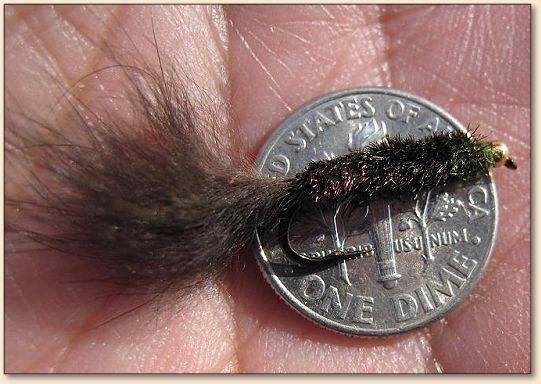

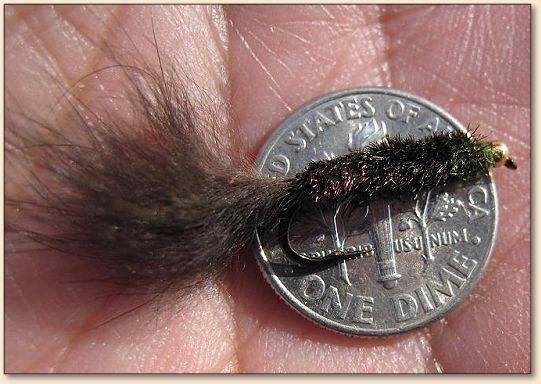

Using my forceps to move aside the fluffy feathers of a marabou

pattern, Renewed Hope arrived in the guise of an olive/copper-bodied,

black-tailed #12 bead-head Woolly Bugger, a fly given to me

(if memory serves) by Texas angler Stew Denton.

Dunking the bugger underwater so that I could massage

its components to squeeze out trapped air bubbles, I next

conducted a drop test to gauge how slowly the saturated

version falls. Ahh…perfect! What I would do now

is revisit some shoreline areas hit earlier, this time using much

longer countdowns so this lightweight bugger could sink very

slowly before bringing it in with ultra-slow retrieves. Maybe

the bluegills weren't hitting today, either, but there was still a

ways to go yet before they could make me believe it.

Sitting thirty feet out in 8 feet of water with my canoe anchored

so that its long axis lay parallel to the shoreline, I threw the WB

ahead and to the left into shallower water, gave the bugger a

15-second countdown and had just begun the retrieve when a

hard hit came. Many happy seconds of bent rod action later,

a thick 9-inch bluegill was unhooked and slipped into my floating

fish basket. The next two casts brought into possession two more

keeper-size 'gills.

The tide had turned. Better yet, during the ensuing flurry I saved

my 00-wt. Sage rod. Following one of my casts, I looked away

from the leader and floating line during the long countdown. My

returning gaze spotted the floating line racing away at high speed

just as the tightline shock impulse hit – perhaps the only thing that

kept that hard-running bluegill from jerking the rod out of my light

grasp. That was a little scary.

After giving up on crappie and switching to bluegills, after quitting

large patterns worked through deep water in favor of a tiny insect

imitator worked slowly through shallower water, in one hour the

little Woolly Bugger captured twelve keeper bluegills – four times

the number of fish I'd caught during the preceding five hours.

Even now, three days later, not a single thing bugs me about

that sudden late burst of good luck. ~ Joe

About Joe:

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

Joe at one time was a freelance photojournalist who wrote the

Sunday Outdoors column for his city newspaper. Outdoor

sports, writing and music have never earned him any money,

but remain priceless activities essential to surviving the

former 'day job.'

|

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.