|

The fishing folks I envy most don't transport their

boat to a lake, pond or river every trip – the boat

is already there. But for me and most others who

fish out of boats, we need a way to get it from home

to wherever we're fishing, and then back again.

Every trip.

A number of people have emailed me asking how I

transport my canoe. This being wintertime and my

local waters getting iced over, now seems a good

time to write something on this subject. At worst,

this article will give readers an idea of what they

don't want to do. At best, it will give some basic

information on rack systems that have worked well

for me. Unfortunately, I have no photos of the first

three racks I used.

The first rack was a "Quick & Easy" outfit. Four

mounts clamped solidly onto the raised rain gutters

on my 1972 Plymouth Duster 2-Dr. The crossbars were

a pair of common steel pipes, each pipe outfitted with

clamp-down gunwale holders that pinned my Grumman

Standard 17-ft. tandem canoe in place.

After buying a 1984 Toyota Tercel 4-dr hatchback,

I cannibalized the Quick & Easy rack so that I

could employ its rain gutter mounts on the Tercel.

I dispensed with the steel pipe crossbars in favor

of pressure-treated 2x4s and bolted those to the

Quick & Easy gutter mounts. After that task was

completed I added custom-fitted homemade gunwale

stops that held my inverted canoe in place. (But

the brackets fit only that specific canoe; no other

canoe could ride in this unique "cradle.") Last,

I carpeted the 2x4 crossbars to reduce abrasion on

the canoe's beautiful wooden gunwales while

loading/unloading. This carpeting was accomplished

by custom-cutting strips of common indoor/outdoor

carpet then gluing the pieces to the top surface

of the 2x4 crossbars using Weldwood cement.

With both of these first two racks I had very little

confidence in the holding power of the gunwale

brackets/braces. This meant tying down the bow

and stern of the canoe every trip, using security

lines attached to my bumpers. Lots of line, lots

of knots; I really enjoyed fussing with the knots.

Personally, I'd have been happy if auto manufacturers

had NEVER stopped building vehicles with raised rain

gutters. Those gutters were extremely handy as

clamp-down points for canoe racks like Thule, Yakima

and the Quick & Easy. But styles change; in what seemed

like only five years time raised rain gutter disappeared

and were succeeded by aircraft door-style rain gutters.

This style change by automakers forced canoe rack

manufacturers to re-design their rooftop connection

hardware.

Around this time, in 1992, I bought a Ford Explorer.

My first SUV, it and had a much longer roofline than

the compact passenger cars I'd owned previously. I

factory ordered my Explorer without the standard luggage

rack, a rack I knew was useless -- even dangerous -- for

use as a canoe carrying platform.

The Explorer had the new-style aircraft door rain

gutters, which forced my customized Quick & Easy

canoe rack into retirement. In its place I bought

a Yakima crossbar set.

My personal preference in any canoe rack is to have

the two crossbars be long enough that I can carry a

pair of canoes side-by-side. Also, I want the two

crossbars to be located the maximum possible distance

apart. (The farther apart the crossbars, the less apt

the canoe is to move about on the rack when hit by

sudden gusts of wind while your vehicle is underway

at highway velocity.)

With rack systems like Thule and Yakima, the only

way to connect the mounts to a modern vehicle's rain

gutters is by purchasing molded steel plates that fit

the unique door shape of the vehicle you own. Okay,

but in my case I was not satisfied with this idea

because an Explorer's front doors and rear doors are

not spaced far enough apart to achieve the tie-down

separation distance I prefer for maximum boat carrying

security.

Luckily for me, Yakima designers anticipated this.

The company sells 'artificial rain gutters' called

Bolt Top Loaders. I bought a pair of these plates

for my rear crossbar and installed the plates directly

onto my roof near the rear hatch. The job required

pulling down the interior headliner so I could visually

find the safest spot to drill holes in the metal roof.

(Not a good idea, drilling blindly and severing your

tail light/brake light/turn signal wiring harness.)

There are few things more nerve-racking than glancing

over and seeing your wife standing like a trigger-happy

prison guard while you drill four permanent holes through

the gleaming roof of a $20,000 SUV so new it still has

its factory stickers in the rear window. I was scared

out of my wits, but determined. See, prior to buying

this SUV I'd made it crystal clear that I would not

co-sign my name to the purchase order unless she promised

that I could custom-install this canoe rack on the vehicle.

No Yakima rackee, no Ford truckee.

I have no photos of the Yakima rack that I put on the

Explorer. But to give you an idea of its stability,

the two crossbars were 9 feet apart. That spread

resulted in a super-secure carry for my boats and

my friends boats for ten wonderful canoe trip-filled

years.

With such a long tiedown spread, I quickly relaxed

to the reality that it was no longer necessary under

normal circumstances to run a bow and stern dropline

from the canoe ends down to my front and rear bumpers.

Only in the most severe high winds would I now connect

droplines.

Also, around the time I bought and outfitted this Ford

Explorer I made the transition from homemade boat

tiedown ropes to Northwest River Supply (NRS) 12-ft.

tiedown straps. NRS straps have a cam lock buckle

that is secure under all circumstances provided the

cam spring is in good working order. (I do have one

15-year old NRS strap whose buckle spring weakened).

So much for my first three racks.

My fourth canoe rack was one I bought after June Newman,

one of my canoeing friends, installed one on her Ford

Ranger pickup. I was so impressed that it motivated

me to replace my aging Ford Explorer with a Ford Ranger

then install the same rack system June had. I've never

regretted either purchase.

Pictured below (and not pictured that well, sorry) is

this Oak Orchard rack system as it appears on the Ranger.

(The Ranger now belongs to my son, Eric, who mountain

bikes more often than he canoes, but he wanted racks

for times when he does canoe.)

This particular rack system is the Pickup Truck Rear

Rack, Deluxe #1 Style made by Oak Orchard, a company

located in Rochester, New York. (You can find them

on the Web.) The design of the rear rack mount is

minimalist but incredibly strong. At first glance

the slender square-tube upright supports appears

flimsy. In truth, once you put a canoe on this rack

it rides like it's set in concrete. Grab your canoe

and shake it: the truck moves, the canoe does not.

One reason being that the tiedown spread (the distance

from cab roof crossbar to tailgate crossbar) is some

9 feet, which combined with the crossbar-mounted gunwale

brackets and NRS straps does not allow any rattling or

lateral movement by the canoe whatsoever.

In the photo below you can see one of the custom-fit

rain gutter door clips that Yakima makes for grabbing

hold of today's aircraft style rain gutters (in this

case a 2002 Ford Ranger). It is necessary to buy the

gutter plates specifically designed for your vehicle's

doors. Substitutes won't do.

The next photo (below) shows one of the vertical square-tube

steel support posts. The base of this post comes with drill

holes already made. The rear crossbar support posts are

bolted to the inside surface of your truck's tailgate area,

at a point just inside the tailgate itself.

This particular model of the Oak Orchard rack is

designed for use with an open truck bed, which is

what many canoeists and kayakers go with. I love

the simplicity and strength of this design, although

on long canoe trips I always had concerns about the

theft of gear during rest stops at restaurants and

such. Still, the convenience of having an open pickup

bed cannot be dismissed for those who like their canoe

trips to involve rapid loading/unloading of gear from

both sides of the truck bed.

Now for the canoe rack setup I have now:

In 2004 I bought a Toyota Tacoma 2x4 pickup.

Initially what I did was remove the Ford Ranger's

Oak Orchard rack and transfer it to my Tacoma.

This task involved drilling new mounting holes

on my Tacoma's tailgate area in order to install

the "nutserts" that hold the rear crossbar support

uprights in place. Also there was a modest purchase

of two door clips to fit the Tacoma's cab door rain

gutters.

But when my son, Eric, expressed a desire for canoe

racks for his pickup so that he could go with me on

trips (or shuttle other boaters), I moved the entire

Oak Orchard rack setup from the Tacoma back onto his

Ranger.

Once I had the Tacoma, and soon after getting divorced,

I decided to buy a "cab high" fiberglass shell for my

pickup bed. This shell would multi-task, providing

hard shelter for my music, canoeing and fishing gear.

Also, the interior of the shell offered a large enough

space that I outfitted and stocked the shell in such a

way as to convert it into a high-tech "micro-apartment."

I lived in this shell, quite snugly and inexpensively,

for 14 months until just recently, and will not hesitate

to move back into it if the need arises.

The Astro shell I bought for my Tacoma pickup did,

however, rule out using an Oak Orchard rear rack

system. I could still employ a Yakima rack system,

though. What I did was use the same type of Bolt

Top Loader plates that I'd installed years earlier

on the roof of my old Ford Explorer. Except now

instead of drilling through a sheet metal roof I

drilled through the roof of a fiberglass shell.

The installation proved trickier than I'd anticipated

due to subtle curvature of the shell's roof making it

hard to find flat attachment points in the area I wanted

the top loader plates to sit.

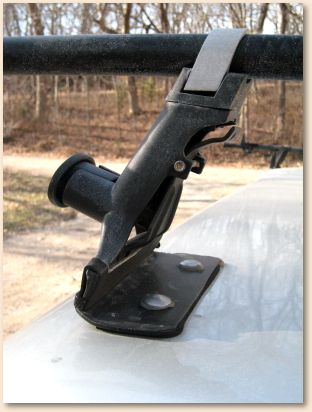

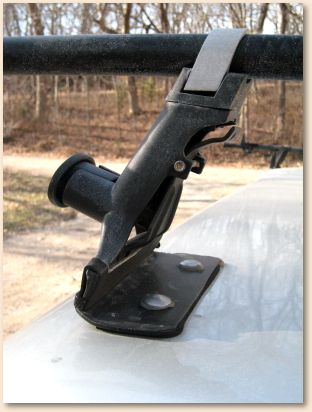

Below are a couple of photos that show one of my

rear crossbar mounts sitting on a Bolt Top Loader

plate. The crossbar mount locks onto the plate

in the same fashion it would clamp onto an old-style

external rain gutter.

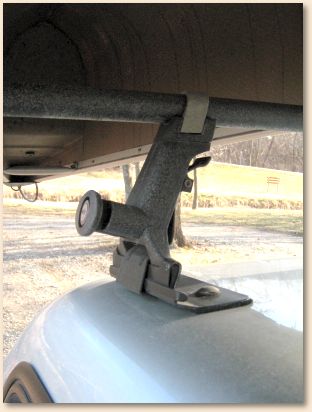

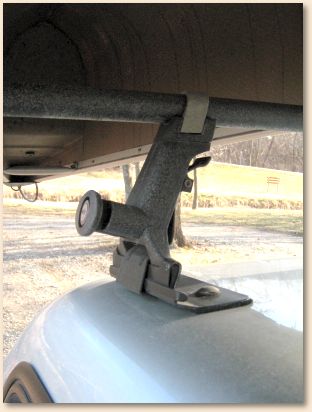

Next, a closeup photo of one of the Yakima door clips.

These clips are shaped specific to fit the Toyota

Tacoma's aircraft style rain gutters. The door clips

secure the front crossbar mount to the roof of my truck

cab. Close the cab door and the clip can't come off

(the secret to the system's strength).

Now for the matter of securing the boat on the rack:

You don't want your canoe bouncing up and down on the

rack crossbars. Nor do you want the canoe yawing left

and right. You don't want that canoe to move, not the

slightest bit. Yakima (and other rack makers) devise

gunwale brackets that must be purchased separately then

attached to the crossbars. They come in sets of four,

and once installed on the bars the brackets can be moved

independently into almost any position along the length

of the bar.

The adaptability of the gunwale brackets lets you put

the canoe on the rack (inverted), line up the boat the

way you prefer, then move the four brackets underneath

the gunwales and tighten them down. This results in a

"cradle" into which you lay your canoe prior to strapping

it down. And Mama, this cradle don't rock. You put your

canoe into it, strap it down tightly, and your pickup

could be turned upside down and shaken and that canoe

won't come off. Just make sure all related mount,

crossbar, gunwale bracket, and strap fittings are

tight and secure.

Below are some closeup photos of my canoe on the rack,

strapped and ready for travel.

The observant reader will notice that on the forward

side of the cab crossbar the NRS strap has a full

twist, while on the aft side of that same crossbar

the strap is flat. This is a trick I use to keep

the straps from humming loudly at highway speed.

If you don't give the forward half of the strap

this full twist, the wind blows across it and makes

it vibrate like the reed in a duck call. But giving

the forward half of the strap a full twist before

cam-locking it, this creates a "spoiler" that disrupts

the airflow over the trailing half of the strap. The

result? No highway hum gets generated by the tightened

down straps.

Next, here's a photo of my Wenonah Rendezvous solo canoe

strapped onto my Tacoma's Yakima rack system. Canoe and

pickup are ready for the road.

An inverted canoe thus held causes very little wind

resistance, which is important because such minuscule

wind resistance does not reduce your vehicle's fuel

efficiency. On the highway your canoe cuts through

the air like a knife.

Last, here's a front angle photo of my Tacoma with

the Wenonah solo on one half of the rack, and an

empty spot next to it. A second set of gunwale

brackets has been attached to the crossbars,

preparations for a second canoe. I am a firm believer

in people buying canoe rack crossbars that are at least

66 inches long. This allows a second boat to be carried,

which is most important when doing canoe shuttles on river

trips.

Hope this story and these photos give you some ideas

on how you can rack and transport your canoe or kayak

if you are thinking about taking up the sport of fly

fishing using a self-propelled watercraft as your

mobile operating platform.

About Joe:

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe's

'day job' is with the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe's

'day job' is with the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

Joe at one time was a freelance photojournalist who wrote the

Sunday Outdoors column for his city newspaper. Outdoor

sports, writing and music have never earned him any money,

but remain priceless activities essential to surviving the

'day job.'

|

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe's

'day job' is with the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe's

'day job' is with the U.S. General Services Adminstration.