|

Horse trails through national wilderness areas get a bad rap

in certain circles, justifiably so in some cases. But it's

doubtful you will hear many complaints from people who fish

the Selway River above Lowell, Idaho. Without the guided

horseback excursions that take place in the Selway River

Valley there would likely be no foot trails for thousands

of trout fishermen wanting to explore the remote waters that

lay miles above the end of the lower Selway's access road.

There I was, at the 2007 FAOL Idaho Fish-In, following my Colorado

fishing buddies Bob and Dan Fike and Ken Sample as they hurried

along one of these horse trails. We were intent on finding some

remote places to fish, and we'd elected to hike some two miles

upriver beyond the last public parking spot.

The chemical components of horse tranquilizers are unknown to me,

but after hiking this trail I can better understand why some horsemen

keep a stash of these pills handy for times when the difference between

living or dying hinges on whether "Trigger" is adequately chilled out.

I can't imagine what a trail horse goes through when walking this trail,

burdened as trail horses often are by 200 pounds of nervous, squirming

"sport." But after hiking this trail I can report that places along

it are so precarious that straying off the path a mere two feet is a

major career blunder, one that will send you tumbling 150-feet almost

straight down a mountainside. Upon impact, your body will crunch onto

boulders or splash into the river.

"Keep your eyes focused on the back of the man walking directly ahead

of you," I told myself (the man in this case being Bob Fink). "Don't

look down; it'll give your feet an excuse to follow your gaze."

I wanted so much to stop for just a second and shoot for posterity

a photo of the astonishingly beautiful Selway, a National Wild and

Scenic River. But I learned years ago while using binoculars to inspect

bald eagle nests on the Kansas River by canoe, that it's all too easy

to lose your sense of balance when peering through optics while your

body is in motion. Here on this horse trail that concern might be

unfounded; nevertheless, I was worried that even if I stood stock

still the simple act of looking through my camera's viewfinder could

cause me to lose my balance and fall.

My three partners today were the fishing buddies who'd adopted me

soon after my arrival at Three Rivers Resort. Bob and Dan Fink

and Ken Sample have been trout fishing many years and the comfortable,

well broken-in condition of their wading gear proves it. Me, on

the other hand...I'd brought to Idaho a pair of stiff, virtually new

wading boots. The prospect of hiking two miles, then struggling

across whatever rocks and boulders we would inevitably encounter

upon locating a fishing spot, and then hiking two miles back to

my pickup...well, call me a weenie if you wish; you'll be exactly

right. Yours truly was hiking this trail in running shoes.

But even in this lightweight attire I was getting left in the

dust by three guys wearing chest waders and felt boots. What's

up with this, I wondered? Okay, I might be 60 years old, one

foot on a banana peel and the other in the grave. But up ahead

strides Bob, a man older than me, and...the distance separating us

keeps increasing?

"You gotta remember," explained Ken later, "the three of us live

in the Colorado Rockies at an elevation of around 8,500 feet? Here

at Lowell it's only 1,500 feet. To us, hiking in a place like

this is like having your car engine fitted with a supercharger."

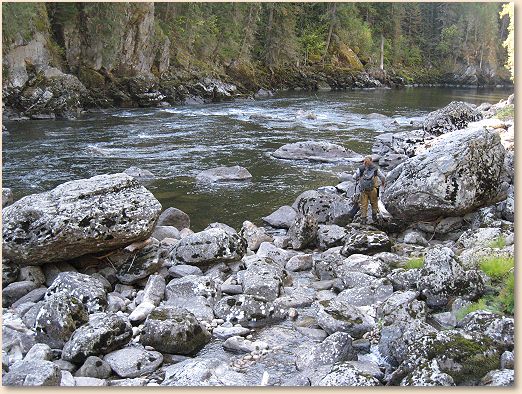

The 2-foot wide horse trail eventually led down off the mountain

flanks to a big gravel bar. Upriver from it lay a rapid so

picturesque that it brought to mind those animated, twinkling

Hamm's and Coors beer signs we old guys, when we were kids, used

to see mounted on the walls of pool halls and beer joints everywhere

decades ago.

Below this rapid lay a wide, deep pool some 125 yards long. Its

volume flowed slowly past the big gravel bar before the streambed

shallowed and the pool's tailwater funneled into the next rapid

downstream.

The day before, I'd fished the Lochsa River first with Ken as my

partner and then Bob. On the Lochsa, Dan and I had been separated

by the serendipity of independent fisherman movement. Today, then,

I wanted to tag along with Dan everywhere he fished and do my best

to stay out of his way so that I could study how he works water

like this.

I was put at ease hearing my buddies remark repeatedly on how big

and wide the Selway is even two miles beyond road's end. They'd

never fished it this high up and expected the channel to be lots

narrower by now. Gaping at this majestic valley with a Midwesterner's

eyes, it struck me that you might need to hike a little bit farther

east - oh, like maybe somewhere off in North Dakota - before this

river gets any narrower. On the hike in, we'd come past pools on

the Selway that are so long, wide and deep that a Navy cruiser can

be floated in them with room to spare all the way around.

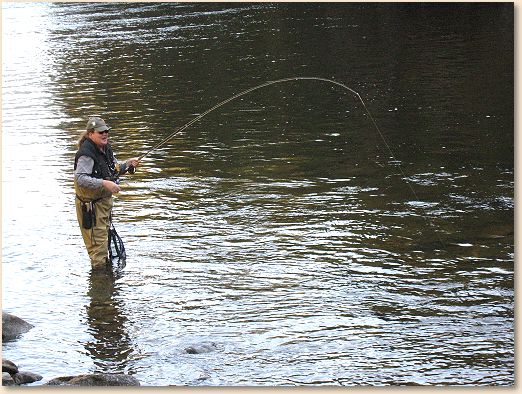

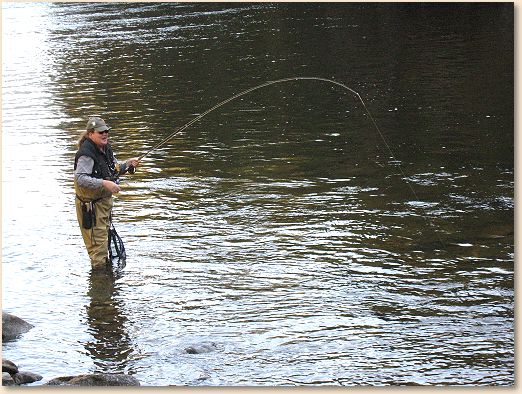

Dan got his rod rigged first, and stepped to the mound for the game's

first pitch. As he did so I moved into photo shoot position. Good

thing, because on his very first throw - a cast targeting pool center

at the tailout - his "Flymph" fly barely touched the water when it

got smacked hard by a good-sized cutthroat.

The party - or so we thought - was on! We split up into pairs,

Bob and Ken going upriver while Dan and I stayed at the pool.

But everyone's hopes for a period of hot action fizzled as minute

after minute ticked away with nobody getting a strike despite

the fact that each guy was using a different fly.

Dan finally conceded the obvious: another hit wasn't going to

happen here. He reeled in and headed downriver, pausing

occasionally to fish pocket water in the rapid's boulder garden.

Here is where I thanked my lucky stars that I was wearing running

shoes.

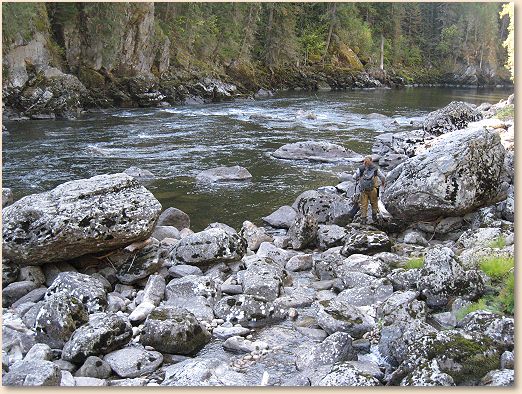

This photo fails to do justice to the physical challenges one

must overcome to move through a boulder field such as this. How

Dan managed to get through with such apparent ease, burdened as

he was with chest waders and boots, was an amazing thing to witness.

And even here, despite my lighter footwear I was consistently left

behind.

Unlike a day earlier on the Lochsa River, when an invigorating

morning dip had delayed the start of my fishing, today on the

Selway I restricted myself to dry land. Not the usual thing a

trout fisher does, I admit, but it let me get with the program

only minutes after Dan began fishing. Again, I'd decided to

trail him everywhere he went, not wanting to lead the way. Now,

if I had a clue what to do in water like this I might have

leapfrogged ahead of him as river fishing partners typically do.

But I knew my own best chance for success was having the guy in

the know be the first to go.

We thus proceeded downriver into the heart of the outflow rapid,

Dan in the lead and staying with his "Flymph" pattern. I went

with a #12 hi-visibility Parachute Adams; in rapids and bouncing

water I love this fly's bright little highway flare topknot that

lets me track its whereabouts as it scoots along the surface.

I might love a Parachute Adams but right now the trout didn't think

very highly of it. By the time I trailed Dan through the rapid's

boulder garden neither he nor I had caught a single fish or had

even one rise. Two good trout flies, zero fish. I finally reached

the pool below the rapid - deep, slow water where presumably a

Parachute Adams would not be a good choice. The cogs in my brain

began turning.

"Okay, here's a deep pool. Trout must live in this pool, and if

they don't want to eat an Idaho-type dry fly I'll just have to 'go

Kansas' on 'em."

This I did by clipping off the Parachute Adams and tying on my

Sweetheart of sweetheart flies - "Old Reliable," a #10 flashback

Hare's Ear Nymph. Then over and over I swam Old Reliable through

different parts of the pool, using assorted presentations at

various depths. If Old Reliable was detected by the fish inhabiting

this pool they were ignoring him utterly.

I yelled to Dan, who was standing a ways downstream, asking if he'd

caught anything yet. He shook his head no. He was working this

second pool's tailwater where a portion of the Selway's volume

angles across a gravel bar and gets squeezed into a narrow,

high-speed chute.

I reached this spot myself about five minutes after Dan abandoned

it to fish the pool immediately below the run. Still no hits on

his Flymph, my Adams Parachute had failed to open and even Old

Reliable was in the dog house. Is there anything in my box that

might catch a fish here?

This is where our day got saved by something Dan had told me 48-hours

earlier, minutes after I'd arrived at Three Rivers Resort. I'd asked him,

Bob and Ken to inspect my fly box and give me their honest opinions:

can any of the flies I've brought from Kansas catch trout in the

Lochsa and Selway?

I was not surprised when they politely pointed to very few of them

as possible winners. But now I recalled one in particular, a longish

orange and brown wiggle-legged fly that Dan had noticed. I've always

called it a centipede imitator and in Kansas have caught largemouth

bass with it. (Its correct name is Pete's Rubber Legs.) Dan told me

it's a fair imitation of a stonefly nymph and as such might prove

useful because stone flies do reside in the Lochsa and Selway rivers.

To me, it was not so much the insect species it represents but

the weight of Pat's Rubber Legs that persuaded me to retire the

lighter-weight Old Reliable and switch to "Plan C". The deep,

fast chute below this angled gravel bar demanded the heaviest

nymph in my box, one that would sink quicker and thus pass closer

to the riverbed, where any trout holding there might spy it. You

know, try to make mealtime a little easier for the fish? We nymph

fishermen are nothing if not helpful.

And it worked, too, just not where and how I thought it might.

What happened was I cast the PRL into the water just above the

drop so that the nymph could "pre-drop" a few inches before it

got swept into what I thought was the chute's sweet spot? The

nymph dutifully sank then shot through the chute (attracting no hits).

Farther downstream the current pulled my line tight and this swung

the nymph over alongside the bank. But instead of immediately

pulling it out for the next cast I let the nymph hang there close

to the bank in the eddy slot, where it began sinking deeper yet.

(The water there looked very shallow, but I knew better.) Only

then did I begin swimming it back toward me using 6-inch strips.

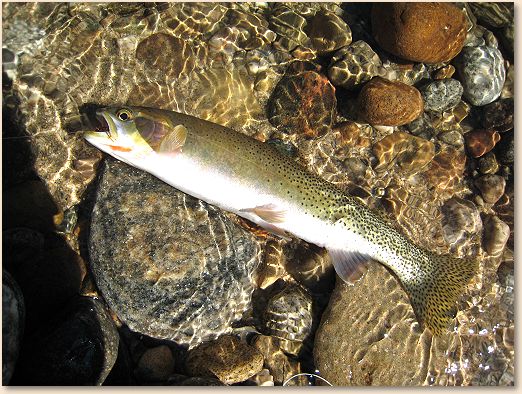

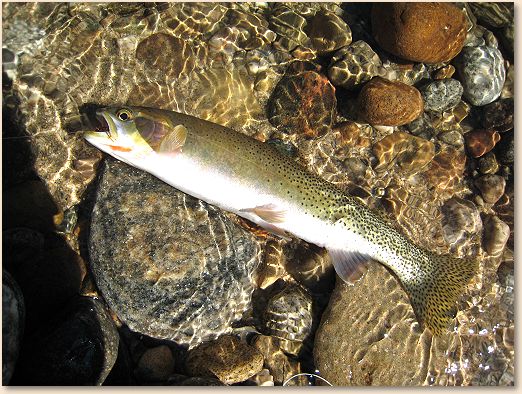

Crunch! came a hit. After a brief fight I landed an 8-inch cutthroat

trout. Yelling down at Dan to alert him to my bent rod, after releasing

this fish I hollered down at him again and told him which pattern I'd

used. Then on the very next cast, after repeating the above tactic I

had another strike but missed the fish, and I told him about that, too.

Dan by now was burned out on not getting any hits. I knew his fly

box held at least one PRL because he'd showed it to me earlier. So

he retired his Flymph, tied on a Pat's Rubber Legs, promptly got

a strike and landed a nice cutthroat. And then another. We'd

finally hit on a pattern the fish liked.

The valley wall went vertical just below where Dan was standing.

Soon he abandoned the spot for lack of any more downriver options

and walked past me with intentions of fishing his way back upstream

through the first rapid and then on to the gravel bar where our 4-man

group had arrived earlier. Once he vacated his place at the end of

the line I moved down there and took it over. For my effort I caught

an 8-inch trout that I initially thought was a rainbow. (But later

that night after describing its coloration, length and body markings

to my FAOL campground mates, they concluded that it was not a true

mountain rainbow but instead a steelhead smolt; that is, a baby seagoing

rainbow trout.)

Soon I followed Dan back upstream. And I didn't follow simply

to continue observing his fly fishing skills. There is something

about finding yourself alone in the Selway River's imposing

boulder-infested stretches, alone even for a few minutes, that

makes you want to stay in constant contact with another person.

Lose your footing here and suffer a bone-breaking knockout fall

in amongst those SUV-size boulders and nobody sees you go down,

if nobody knows where in the world you disappeared to, it could

take a rescue party hours, perhaps days to find you. The Wild

and Scenic Selway River is more than intimidating, more than humbling.

It's beautiful as all get-out, but the place is sorta spooky if you

ask me.

Once we got back to the big gravel bar (I took an easier, higher

route across smaller rocks while Dan took the ultra-craggy boulder

route alongside the river channel, and still he beat me back!) we

commenced working the big pool again, both of us still casting the

"Fly of the Day." Dan picked up another cutthroat at the pool's

tailwater almost in the exact spot where two hours earlier he'd

scored using his Flymph.

For the first time all day I leapfrogged him, forty yards maybe,

so that I could work the pool at a point higher upstream. Almost

immediately my PRL took a hit, which I missed. I could see a fish

swimming behind the fly, mouthing it repeatedly until my retrieve

brought the nymph into water so shallow that the fish broke off

its harassing pursuit.

Whether this was the same fish I caught about 30 casts later, who

knows? I didn't care; it just felt good catching a beautiful

cutthroat trout while standing on that big, open gravel bar with

no boulders or mountain walls crowding me.

Here's how it happened: For about ten minutes Dan had been giving

off body language indicating he thought it time for us to leave.

I, too, felt it was getting late in the day. So I took it upon

myself to quit first. While absent-mindedly retrieving my last

cast using plain-Jane turns of the reel handle, Murphy's Law paid

a visit in the form of a 12-inch western cutthroat that apparently

prefers a crude presentation to the finesse version.

This fish kept our noses to the grindstone a while longer, but

not much. We hadn't seen Bob or Ken since our teams split up.

Dan said it was likely they'd already hiked back to the jump-off

point. I agreed. So we left and sure enough, Ken and Bob were

waiting for us at the parking area.

Driving back down the valley road to Three Rivers Resort, foremost

in my mind was not the great fun I'd just had catching and releasing

four trout; instead, it was the sheer, overwhelming presence of the

Selway. While spending only a few hours amidst a tiny sampling of

this huge, raw country I'd began feeling for the first time in my

life a gut-level respect for the courage and toughness of the Lewis

and Clark Expedition. That small group had visited this river long

ago, following no roads, using no motorized vehicles. They'd come

to this forbidding valley supported by very few supplies and they

came despite the constant risk of life-threatening disease and injury.

They entered this valley and many others knowing that a violent encounter

with a grizzly bear could happen around the next tree or boulder ahead.

And driving down the valley toward camp I felt also a deep sadness

for the wealth that has been taken from the Selway and the Lochsa

rivers; indeed, for the wealth that our nation of sport fishers

has had taken from us by the machinations of competing bureaucracies

and porkbarrel politics. Not that long ago, in the mid-twentieth

century before all the big dams got built on the Columbia River's

watershed, steelhead trout and wild salmon from the Pacific Ocean

migrated far up the Selway, the Lochsa and other Idaho rivers large

and small; they migrated even into the tiniest brooks that trickle

across upland hay meadows. Absent today's impassable man-made

obstructions these fish muscled their way through pools, rapids

and riffles in such boisterous, uncountable millions that history

records incidents where horse teams being led across river fords

would panic at the sight and gallop away in terror.

I was driving now beside this shadow, this echo of an endless

bounty that maps still call the Selway River, glanced down at

it when road conditions permitted and wondered, "What monstrous

thing have we done to this place? What are we doing?" ~ Joe

About Joe:

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

Joe at one time was a freelance photojournalist who wrote the

Sunday Outdoors column for his city newspaper. Outdoor

sports, writing and music have never earned him any money,

but remain priceless activities essential to surviving the

former 'day job.'

|

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.

From Douglas County, Kansas, Joe is a former municipal and

federal police officer, now retired. In addition to fishing, he hunts

upland birds and waterfowl, and for the last 15 years

has pursued the sport of solo canoeing. On the nearby

Kansas River he has now logged nearly 5,000 river miles

while doing some 400 wilderness style canoe camping

trips. A musician/singer/songwriter as well, Joe recently

retired from the U.S. General Services Adminstration.