|

Outdoors sports shows are excellent scenarios where one

can meet other anglers, buy fishing gadgets, books, rods

and other stuff that one doesn't necessarily need, but

feel compelled to have anyway. All these things would

end up piled somewhere, most probably, in the house. The

problem with piling this stuff somewhere in one's home - and

not finding it when it is needed - is, at times, one of the

reasons for buying more of it. Our apartment (which isn't

big at all) is filled with fishing equipment, brochures,

books, magazines and lots of fly-fishing videos. In addition,

there are also books from our respective professions, our son's

toys, and a bunch of souvenirs from all around the globe.

Needless to say, our living space has been shrunken quite a

bit, but I know that we aren't alone in this madness, as

piling stuff seems to be a very contagious illness among anglers

anyway, or anyone who has passion for her/his hobby. After

visiting a particular outdoor sports show in Philadelphia, we

returned home with the usual pile of brochures to peruse,

materials with which to tie our favorite flies, and a Renzetti

fly-tying vise. Little did I know then that this vise would

become my companion for quite a long time, as from that moment

on, I got hooked on fly-tying.

Re-creating fly patterns from our fly-tying book's collection

and creating new ones became my new hobby. As a result, Jorge

would seldom get a turn at the vise, which gave him a good

reason to buy another one. On many occasions, Jorge and I

worked side-by-side, tying well-known patterns or designing

and tying new ones. Sometimes, each of us worked alone, but

alone or together, time seemed to fly when we were engaged in

the task of tying flies. And with a hectic schedule, finding

time to relax was not an easy chore. This is why fly-fishing

and fly-tying became effective ways for me to handle stress.

Both hobbies proved to be quite effective, particularly when

my parents, brother, and dissertation advisor passed away, all

within a short period of time (in 1992). For quite a while I

was breathing, eating and sleeping fly-fishing and fly-tying.

That's me wearing my hat with many of my own tied flies on the left.

This not only helped to decrease my stress level but also helped

me to focus on my work at the university, making my grieving

process more manageable. I felt so relaxed that stress was

seldom able to find its way into my mind no matter how hard

it tried. So it can be said that wanting to feel relaxed

caused me, in part, to get hooked on fly-tying. The other

reason for tying more of them was my bad habit of leaving

several flies tangled on tree branches.

Re-creating fly patterns from our fly-tying book's collection

and creating new ones became my new hobby. As a result, Jorge

would seldom get a turn at the vise, which gave him a good

reason to buy another one. On many occasions, Jorge and I

worked side-by-side, tying well-known patterns or designing

and tying new ones. Sometimes, each of us worked alone, but

alone or together, time seemed to fly when we were engaged in

the task of tying flies. And with a hectic schedule, finding

time to relax was not an easy chore. This is why fly-fishing

and fly-tying became effective ways for me to handle stress.

Both hobbies proved to be quite effective, particularly when

my parents, brother, and dissertation advisor passed away, all

within a short period of time (in 1992). For quite a while I

was breathing, eating and sleeping fly-fishing and fly-tying.

That's me wearing my hat with many of my own tied flies on the left.

This not only helped to decrease my stress level but also helped

me to focus on my work at the university, making my grieving

process more manageable. I felt so relaxed that stress was

seldom able to find its way into my mind no matter how hard

it tried. So it can be said that wanting to feel relaxed

caused me, in part, to get hooked on fly-tying. The other

reason for tying more of them was my bad habit of leaving

several flies tangled on tree branches.

When we went fishing, Jorge would sometimes notice that I

wasn't casting and would say, "Marta, to catch a fish, your

line has to be in the water, and you have to cast close to

where the fish is rising, or where you think the fish is."

Following his advice I would try to cast wherever I saw a

rising fish or where my fishing instincts told me I should

cast. At times, I could see a fish rising from underneath

bushes or behind trees. His splash or sudden movements seemed

to be saying, "Hey, Marta, here I am, see if you can catch me."

Rising to the challenge, I would cast towards where the fish

was. If my fly presentations were good (and if the fish was

looking for food) it would take my fly. Next thing I'd know,

I'd be releasing a fish. Otherwise, my fly would be added to

the bobbers, lures and fishing lines that had become permanent

tree ornaments.

When we went fishing, Jorge would sometimes notice that I

wasn't casting and would say, "Marta, to catch a fish, your

line has to be in the water, and you have to cast close to

where the fish is rising, or where you think the fish is."

Following his advice I would try to cast wherever I saw a

rising fish or where my fishing instincts told me I should

cast. At times, I could see a fish rising from underneath

bushes or behind trees. His splash or sudden movements seemed

to be saying, "Hey, Marta, here I am, see if you can catch me."

Rising to the challenge, I would cast towards where the fish

was. If my fly presentations were good (and if the fish was

looking for food) it would take my fly. Next thing I'd know,

I'd be releasing a fish. Otherwise, my fly would be added to

the bobbers, lures and fishing lines that had become permanent

tree ornaments.

A smallie caught using my non-scientific method of fly selection!

On some trips, I was lucky enough (or perhaps I had become

more skillful, who knows?) to cast and fish throughout the

day using the same fly. Thus, I would be able to spend more

time fishing and less time tying on a new fly. This wasn't

always the case though. Sometimes, after having been nibbled

by hungry panfish, chain pickerels, or bass, the fly would

need to be put away for emergency repairs or to be discarded.

It would then be time to select and tie a new one. You must

know though, that my fly selection wasn't always based on what

I have read and learned from the experts. On occasions, I

would select a fly based on my taste for it and not because

it matched a natural.

I would ask myself, "If I were a fish,

what kind of a fly would interest me the most?" After a short

but profound philosophical discussion with myself about which

fly to use, I would look into my fly box and select the one fly

I felt most attracted to, based on its color, material, size,

type and shape. My rationale? "Perhaps the fly selected would

be as attractive to the fish I was after, as it was to me."

Wanting to prove my hypothesis, I would begin to cast, and let

me tell you, this very simple non-scientific approach of

selecting a fly gave me good results on many fishing trips!

What can I say? Any technique that can help you catch a fish

should be given a chance!

I would ask myself, "If I were a fish,

what kind of a fly would interest me the most?" After a short

but profound philosophical discussion with myself about which

fly to use, I would look into my fly box and select the one fly

I felt most attracted to, based on its color, material, size,

type and shape. My rationale? "Perhaps the fly selected would

be as attractive to the fish I was after, as it was to me."

Wanting to prove my hypothesis, I would begin to cast, and let

me tell you, this very simple non-scientific approach of

selecting a fly gave me good results on many fishing trips!

What can I say? Any technique that can help you catch a fish

should be given a chance!

If a fly that I liked got tangled on a tree branch or underneath

the water surface (and if it was the last of its kind in my fly

box) I would want to get it back. I would ask Jorge to paddle

to the tree branch so I could pick up the tangled fly. But

picking it up wasn't always an easy task. First, Jorge wasn't

always willing to go pick it up, because for him, the time spent

getting the tangled fly could be used for fishing. "Forget

about that fly and just tie a new one," he would say, but at

my insistence, we would go to pick it up. Secondly, some of

the branches where my fly got tangled might be intertwined

with a poison ivy plant, and experience taught me that not

knowing what poison ivy looks like could make my life miserable

for almost two weeks! I know this from the one time that I,

unfortunately, unwittingly encountered it. As a result, I

developed an extremely allergic reaction to the poison ivy plant,

which caused me a visit to my primary care doctor. After this

incident I avoid getting close to this plant, for fear of suffering

its rage again.

Despite my experience with poison ivy, being able to get my

fly beyond, underneath, around or besides tree branches became

the target of my casting. I definitely wanted to hook and

release a fish, and no tree branch was going to get in my

way! Patiently, I kept on practicing my fly-casting, and

all this practice paid off. That is, most of the time my

fly landed exactly where I wanted it to, and not on a tree

branch. Other times...well, nobody is perfect!

As you can tell, I became truly hooked on fly-fishing and

fly-tying. My interest was such, that I began to create

my own designs and sent them out to fly-tying contests in

the U.S.A. I knew that hundreds of excellent fly-tiers

participated in these contests, but I couldn't help but

to feel disillusioned when my designs didn't even make

it to the runners' up category. Then again, as the saying

goes, no one is a prophet in her/his own land. But one

day, an article from the Still Water Trout Angler Magazine

from London caught my attention. Terry Griffiths, one of

the magazine-contributing editors, was encouraging readers

to send out their version of the Damsel Renegade's fly

pattern for the magazine contest. Jorge encouraged me

to enter the contest, and so I did.

My Damsel's Renegade design.

My Damsel's fly pattern design had twin clipped hackles

in yellow with white and fuchsia colors on a purple and

green chenille body. I sent it to London and to my surprise,

it appeared in the next Still Water Trout Magazine issue

of March 1994, as one of the versions Griffiths found

interesting enough to give it try! He particularly

liked the clipped hackle effect and the twin hackles

of my fly.

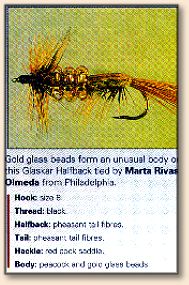

At the time, another hobby of mine was beading. That is,

I would make all kinds of jewelry (e.g. earrings, necklaces,

rings) with beads. After reading about how a particular

Norwegian woman crochets her flies, I asked myself, "Why

not use beads to tie some fly patterns and see what happens?"

The opportunity to create a beaded fly pattern presented itself

rather quickly. Once again, Terry Griffiths was asking readers

to send their version of an Alaskan Halfback pattern. I decided

to tie mine using gold glass beads for the body (sewn together),

pheasant tail fibers for the halfback and tail, and red cock

saddle for the hackle.

When I began to gather my materials, I found out I didn't

have any pheasant feathers. A trip downtown to the Orvis

store, where we were regular customers, was necessary

(Unfortunately, this Orvis store which was located in the

heart of Philadelphia on Walnut Street, to be exact, has

since moved to another location, outside the city limits).

Mary, the store manager, and all the other employees were

very friendly and they were great fly anglers as well.

After the usual greeting and must-do fishing chat, I asked

Mary, "Do you have pheasant feathers at the store?"

"Unfortunately not," she said. As I explained to Mary my

reasons for wanting to buy pheasant feathers, one of the

other employees (I apologized for not being able to remember

his name, but my memory is not as good as it used to be!),

having overheard my conversation with Mary, went to the back

of the store and returned with a ladder. Next thing I knew,

the gentleman was climbing the ladder and plucking some

feathers from a mounted pheasant which was way up high on

the shelf. It had been there for quite a while, mainly for

the store's decoration purposes. Down the ladder he came

and said, "Here Marta, take these feathers with you and

tie a nice fly." His generosity touched my soul and thanking

him profusely, I said, "I am going to try my best."

Mary, the store manager, and all the other employees were

very friendly and they were great fly anglers as well.

After the usual greeting and must-do fishing chat, I asked

Mary, "Do you have pheasant feathers at the store?"

"Unfortunately not," she said. As I explained to Mary my

reasons for wanting to buy pheasant feathers, one of the

other employees (I apologized for not being able to remember

his name, but my memory is not as good as it used to be!),

having overheard my conversation with Mary, went to the back

of the store and returned with a ladder. Next thing I knew,

the gentleman was climbing the ladder and plucking some

feathers from a mounted pheasant which was way up high on

the shelf. It had been there for quite a while, mainly for

the store's decoration purposes. Down the ladder he came

and said, "Here Marta, take these feathers with you and

tie a nice fly." His generosity touched my soul and thanking

him profusely, I said, "I am going to try my best."

I left the store carrying with me not only the necessary

materials to tie my fly, but good luck wishes from everyone.

Once at home, I began to tie my beaded version of the Alaskan

halfback. When finished, I sent it to Terry Griffiths in

London. He named it the Glasskar Halfback and included it

in the June of 1994 issue of the magazine as an honorable

mention. I am very thankful to Terry Griffiths for

recognizing the fishing potential of both, my Damsel Renegade

and Glasskar Halfback flies. ~ Marta

|

Re-creating fly patterns from our fly-tying book's collection

and creating new ones became my new hobby. As a result, Jorge

would seldom get a turn at the vise, which gave him a good

reason to buy another one. On many occasions, Jorge and I

worked side-by-side, tying well-known patterns or designing

and tying new ones. Sometimes, each of us worked alone, but

alone or together, time seemed to fly when we were engaged in

the task of tying flies. And with a hectic schedule, finding

time to relax was not an easy chore. This is why fly-fishing

and fly-tying became effective ways for me to handle stress.

Both hobbies proved to be quite effective, particularly when

my parents, brother, and dissertation advisor passed away, all

within a short period of time (in 1992). For quite a while I

was breathing, eating and sleeping fly-fishing and fly-tying.

That's me wearing my hat with many of my own tied flies on the left.

This not only helped to decrease my stress level but also helped

me to focus on my work at the university, making my grieving

process more manageable. I felt so relaxed that stress was

seldom able to find its way into my mind no matter how hard

it tried. So it can be said that wanting to feel relaxed

caused me, in part, to get hooked on fly-tying. The other

reason for tying more of them was my bad habit of leaving

several flies tangled on tree branches.

Re-creating fly patterns from our fly-tying book's collection

and creating new ones became my new hobby. As a result, Jorge

would seldom get a turn at the vise, which gave him a good

reason to buy another one. On many occasions, Jorge and I

worked side-by-side, tying well-known patterns or designing

and tying new ones. Sometimes, each of us worked alone, but

alone or together, time seemed to fly when we were engaged in

the task of tying flies. And with a hectic schedule, finding

time to relax was not an easy chore. This is why fly-fishing

and fly-tying became effective ways for me to handle stress.

Both hobbies proved to be quite effective, particularly when

my parents, brother, and dissertation advisor passed away, all

within a short period of time (in 1992). For quite a while I

was breathing, eating and sleeping fly-fishing and fly-tying.

That's me wearing my hat with many of my own tied flies on the left.

This not only helped to decrease my stress level but also helped

me to focus on my work at the university, making my grieving

process more manageable. I felt so relaxed that stress was

seldom able to find its way into my mind no matter how hard

it tried. So it can be said that wanting to feel relaxed

caused me, in part, to get hooked on fly-tying. The other

reason for tying more of them was my bad habit of leaving

several flies tangled on tree branches.

I would ask myself, "If I were a fish,

what kind of a fly would interest me the most?" After a short

but profound philosophical discussion with myself about which

fly to use, I would look into my fly box and select the one fly

I felt most attracted to, based on its color, material, size,

type and shape. My rationale? "Perhaps the fly selected would

be as attractive to the fish I was after, as it was to me."

Wanting to prove my hypothesis, I would begin to cast, and let

me tell you, this very simple non-scientific approach of

selecting a fly gave me good results on many fishing trips!

What can I say? Any technique that can help you catch a fish

should be given a chance!

I would ask myself, "If I were a fish,

what kind of a fly would interest me the most?" After a short

but profound philosophical discussion with myself about which

fly to use, I would look into my fly box and select the one fly

I felt most attracted to, based on its color, material, size,

type and shape. My rationale? "Perhaps the fly selected would

be as attractive to the fish I was after, as it was to me."

Wanting to prove my hypothesis, I would begin to cast, and let

me tell you, this very simple non-scientific approach of

selecting a fly gave me good results on many fishing trips!

What can I say? Any technique that can help you catch a fish

should be given a chance!

Mary, the store manager, and all the other employees were

very friendly and they were great fly anglers as well.

After the usual greeting and must-do fishing chat, I asked

Mary, "Do you have pheasant feathers at the store?"

"Unfortunately not," she said. As I explained to Mary my

reasons for wanting to buy pheasant feathers, one of the

other employees (I apologized for not being able to remember

his name, but my memory is not as good as it used to be!),

having overheard my conversation with Mary, went to the back

of the store and returned with a ladder. Next thing I knew,

the gentleman was climbing the ladder and plucking some

feathers from a mounted pheasant which was way up high on

the shelf. It had been there for quite a while, mainly for

the store's decoration purposes. Down the ladder he came

and said, "Here Marta, take these feathers with you and

tie a nice fly." His generosity touched my soul and thanking

him profusely, I said, "I am going to try my best."

Mary, the store manager, and all the other employees were

very friendly and they were great fly anglers as well.

After the usual greeting and must-do fishing chat, I asked

Mary, "Do you have pheasant feathers at the store?"

"Unfortunately not," she said. As I explained to Mary my

reasons for wanting to buy pheasant feathers, one of the

other employees (I apologized for not being able to remember

his name, but my memory is not as good as it used to be!),

having overheard my conversation with Mary, went to the back

of the store and returned with a ladder. Next thing I knew,

the gentleman was climbing the ladder and plucking some

feathers from a mounted pheasant which was way up high on

the shelf. It had been there for quite a while, mainly for

the store's decoration purposes. Down the ladder he came

and said, "Here Marta, take these feathers with you and

tie a nice fly." His generosity touched my soul and thanking

him profusely, I said, "I am going to try my best."