|

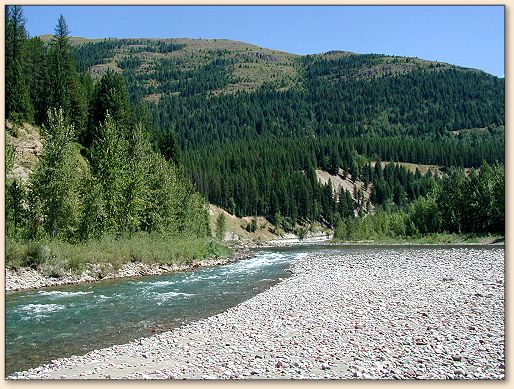

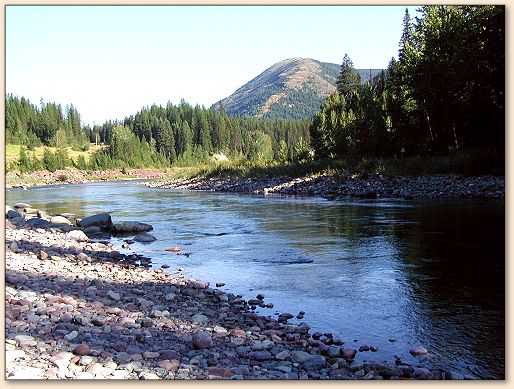

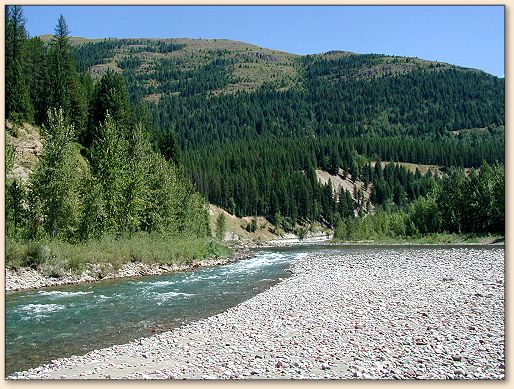

The first thing that hits you is the smell. Nothing

smells quite like a healthy freestone river in the

American west, and the Middle Fork of the Flathead

River is a perfect example of what a remote location

and a Wild and Scenic designation can do to preserve

what must be pretty close to a pristine fishing experience.

After flying into Kalispell, Montana and spending a

few days with family at Whitefish Lake, my trip started

one crisp August morning at the Glacier Raft Company's

outdoor center a half mile west of Glacier Park's west

gate on U.S. Highway 2. That's where I met guide Dan

Harrison for what would be a truly memorable day of

fly-fishing.

After picking five or six likely suspects out of the

center's substantial inventory of hand tied flies, we

were off for a half hour drive to the east on Highway

2 as it runs upstream along the Middle Fork, and the

western border of Glacier National Park.

We put our two-seat raft into the water at the Pinnacle

access point, less than 100 yards off the highway. As

Dan was loading gear, I peered into the crystal clear

water and instantly spotted a 2-inch long gray Stone

Fly skittering across the surface. I pointed this out

to Dan, who gave me a knowing nod and invited me to

take my place on the high seat up front.

Dan is a 25-year-old molecular biologist by training,

and a former fish-habitat biologist with the Maryland

Department of Fish and Game who isn't ready to get off

the river for a "real job" any time soon. When it came

to explaining the Middle Fork's unique feeding patterns,

biota, and fishing strategies, I knew that he knew;

if you know what I mean.

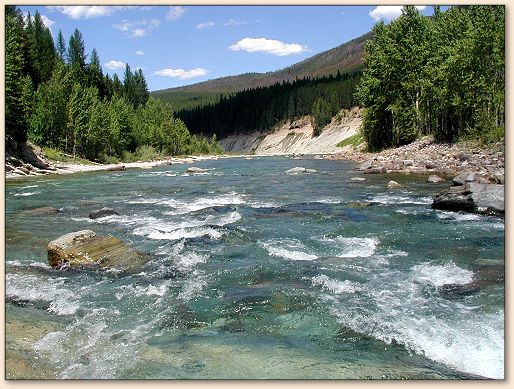

Nosing the pontoon downriver, we cruised the first

100 yards of what would be a 16 mile journey through

some of the most spectacular country, and pristine

river, I've had the pleasure of experiencing. Water

conditions from about mid-July through early August

are just about perfect: too low for the heaviest

rafting crowds, but high enough to make the river

entirely floatable for fishing trips.

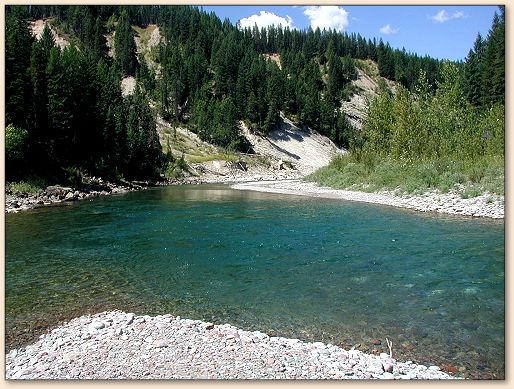

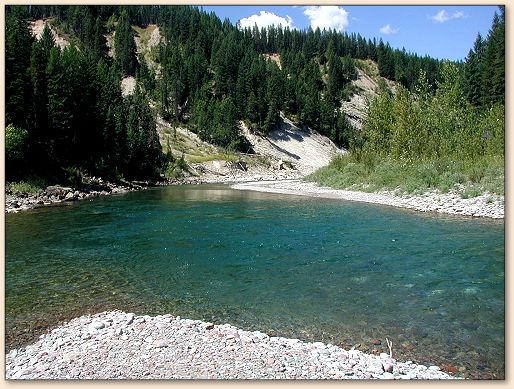

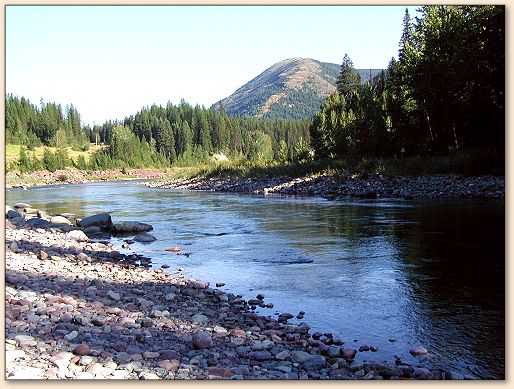

The first thing you notice onboard is the stunning

clarity of the water. Gliding over 50-foot deep azure

pools, one could easily see straight to the bottom.

Deeply submerged boulders provide plenty of cover for

hungry Westslope Cutthroat and Bull Trout, which monitor

the surface for any promising ripple once temperatures

rise enough for insect activity to begin. This is

something that was hard to get used to. Fishing here

isn't early; it's late because of the extremely low

temperatures of the water overnight and into the early

morning.

Our setup was fairly straightforward: A two-piece

graphite 5-weight rod and reel combination, and a short,

7-foot mono leader with a 4-5x tippet. On the business

end of the rig was a "Fat Albert," which to the rest of

the world is a size six foam and rubber stonefly with a

small parachute. We fished a gray version most of the day,

but also toyed with an orange Fat Albert and a Red Wulff

when we thought we'd educated a big one a couple of times.

Mostly though, the foam stonefly was the meal ticket du jour.

Dan and I started working together well very early on.

He'd set me up right or left, suggest mends, and say,

"this is lookin' fishy" when he liked the water, and my

fly's float. On my third or fourth cast as he quietly

murmured, "great float, great float," we got the first

strike. It came in a choppy section of deep blue tail

water alongside a series of boulders. The surface roiled

as an eager Cutthroat took a swipe at my foam offering.

I did not hook him.

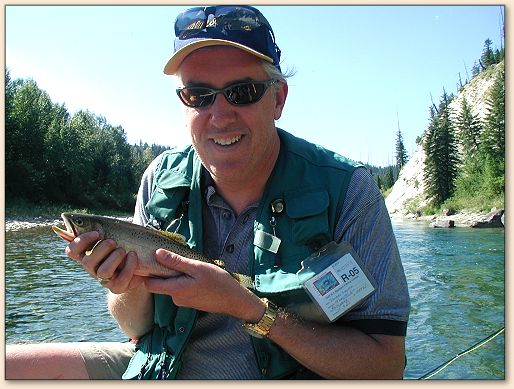

Fishing in gin clear water takes a little patience. I'm

not used to casting to sighted fish, and the tendency to

jump-the-strike is strong when you can actually see a

streaking silver bullet rushing your fly from ten or 20

feet down. After a while though, you get it right, and

you've lip-hooked your first Weststlope Cutthroat.

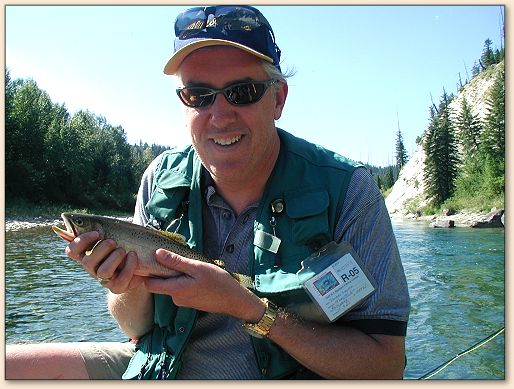

I have nothing but good things to say about Rainbow, Brook,

and Brown trout. They are friends of mine, and I value their

company. However, no trout I've ever caught comes anywhere

close to pulling as hard as the Westslope Cutthroat.

Inch-for-inch, they are the hardest fighting freshwater

fish I've ever come across. Even a 10-inch Westslope will

run line off your reel and make many valiant attempts for

the strong mid-river current, and deep lies he knows at

the bottom. This is a catch-and-release section of river

though, and in my mind, "horsing" the fish a little is

preferred to keep them from exhaustion.

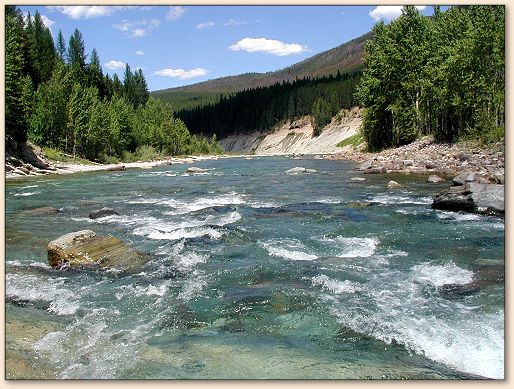

The river is a geologist's dream with strange outcroppings,

shelves, sharply defined striations of layered rock,

undercut subsurface shelves, and precipitous drop-offs

that teem with hungry trout. The river's parent rock,

Argillite, isn't considered to be too fish-friendly when

it comes to producing nutrients, but the fish population

seemed very robust in most of the stretches we fished.

Bear in mind too that we fished in the "recreational"

section of this river, downstream from the fly-in sections

that run through the Great Bear Wilderness.

As we worked out way downstream, the action got hotter

as we moved toward midday, and the insect activity

increased. Dan helped me read the foam lines, and

encouraged me to cast into heavier water than I would

normally select. The aggressive cutthroat did not

disappoint, eagerly slapping the bobbing Fat Albert

with reckless abandon.

We actually raised quite a few fish dragging the bug

on the turn. Dan warned me that this breeds bad habits

among the novices who, once they see this, are reluctant

to go back to trying for that perfect dead float. In fact,

during our lunch break, I caught a 14-incher while stripping

line and dragging the bug upstream six inches from the

shoreline. I saw him follow all the way from mid-channel,

and figured I'd just "troll" until he hit: Which he did.

Hard. Most of our 20 or so fish were taken on a traditional

dead float though, especially the two big ones we landed.

It was just before noon that we had a nice 40 or 50-foot

float going. We were fishing the North bank of the river

right on the heavy current where the river turned from

robin's egg to navy blue. In a flash, a larger silver

slab curled over the top of my fly and started pulling

my tippet toward some nook in a subsurface boulder field.

I set the hook, and felt the heavy pull of something

out-of-the-ordinary. This fish meant business.

I had several yards of stripped line at my feet and

hand-played the fish on its initial blinding run into

the heavy current. But I knew I wanted this fish on

the reel, so after paddling-away at the little Orvis

to take up the slack, I got it done, after what seemed

like an hour.

By this time, our fish was not very happy. Yes, the

meaty beast was finally on the reel, but that didn't

stop him from immediately stripping my fly line with

abandon. This time though I wasn't relying on my marginally

reliable fingertip drag to keep him from breaking me off.

I had the reel palmed as he made a play for my backing.

The Westslope Cutthroat isn't a jumper. No, he's a head

shaker, a strong runner, and a cunning strategist. This

fish would rest until I tried to put a little pressure

on him. At that point he would shake his head. Then,

when sensed that I just about had the reel locked-down

with my palm, he'd make another sharp run in hopes, no

doubt, of breaking me off.

After 15 minutes of this, Dan finally netted what turned

out to be the first of two 16-inch fish we'd take that

fine summer day. Dan told me they were a couple of the

larger Westslopes that had been landed this season.

Actually, even after a couple of these 15 minute fights,

I bulled-the-fish-in a little more than one might usually

do, again, in hopes of not bringing them to exhaustion.

Dan tells me that hooking mortality is actually pretty

low since the Westslope is a hearty species. That's good

to hear, but they're a resource that's worth taking extra

measures to protect.

Despite all the new development around Kalispell,

Whitefish, and West Glacier, the Middle Fork of

the Flathead River is still a great fishing

experience. The presence of U.S. Highway 2 spooks

me a little, as does the heavy overnight rafting

trade. But if managers can at least maintain what

we have there now, it is a wonderful resource that

offers a unique dry fly fishing experience.

There is nothing like a surface strike, and with

the right conditions and the right knowledge, a

memorable experience is within fairly easy reach

on the middle fork of Montana's Flathead River.

~ Tom Layson

Resources:

Glacier Raft Company: 1-800-235-6781, https://www.glacierraftco.com/

Horizon Airlines: https://www.alaskaair.com/

Montana Fish and Game: https://fwp.state.mt.us/

About Tom:

Tom Layson is a resident of Lopatcong Township,

New Jersey and works as the anchor at News 12 New

Jersey, a 24 hour cable TV news service. You can

visit his personal website at:

www.tomlayson.com

|