|

As many anglers know, the Big Horn River has

experienced lower than average flows for the

past three years. For instance, over the past

two years the average flow has been 1,500 cubic

feet per second (cfs) while the normal average

low flow would be 2,500 cfs. Along with the low

flows have come some substantial changes in the

trout fishery and the aquatic ecosystem.

Perhaps the most notable change has been the dramatic

decrease in the number of trout per mile. Back in

the good old days of the mid-90s the total number

of brown and rainbow trout per mile in the upper

river was estimated to be 7,200. Nowadays the

figure is pinned at 1,600.

What has happened? Well, one obvious difference

is the decrease in the amount of surface acres

per mile of river. Many of the side channels and

shallow riffles are high and dry. Consequently,

there are fewer places for trout to live.

Another aspect of the loss of the side channels

has been that the young of the year trout have to

inhabit the main channel where the big browns can

feed on them. For the first couple of years of the

diminished flows, the browns decimated the young

fish and all but eliminated the year classes.

What isn't reflected in the population per mile

estimates is the average size of the trout. Unlike

terrestrial animal populations, population ecologists

don't express the carry capacity of a stream in numbers

per surface acre but in pounds per surface acre. While

the number of fish per surface acre is down markedly,

the average size of the trout has increased dramatically.

Back in the good old days, the average brown was about

14 inches while average rainbow was about 16 inches.

Nowadays the browns and rainbows are between 18 and

20 inches.

The brown trout have had the opportunity to become what

I call, "Real brown trout." What I mean is that in

free-stone streams, brown trout normally switch from

an aquatic invertebrate to a predominantly fish diet

when the browns reach about 16 inches in length.

Subsequently, the free-stone browns would become

lunker-sized and hard to catch. The Big Horn has

few baitfish species, particularly in the upper

stretches. Previously the browns would have to

continue to feed on the invertebrates. They would

also have to feed continuously since they couldn't

obtain enough food to be full. The habit of

continuously feeding made the browns more susceptible

to being caught by anglers.

When there were large numbers of smaller 12 to 16-inch

brown trout in the river, many of the larger browns

would become gaunt and starve to death because they

couldn't eat enough of the small invertebrates to

maintain condition.

During the past couple of seasons the browns have

become harder to catch and also have sported girths

that we had up until then only seen on rainbows.

In short, the small trout diet has enabled the browns

to be more like their free-stone stream cousins.

During the heydays of the Big Horn, the brown trout

outnumbered the rainbows about six to one; presently

the ratio is close to even with maybe the rainbows

holding a slight edge. According to Montana Fish,

Wildlife & Parks fisheries biologist, Ken Frazer,

"It is typical for rainbows to be the predominant

species in a tailwater fishery; the change that is

occurring is not exceptional."

A slight digression is necessary at this point. Last

year there were erroneous reports that there were

only 800 trout per mile. The persons who posted this

information had not read the population estimate

correctly. The statistical model used for estimating

the population is called the Lincoln Method or Mark

and Recapture. The method entails capturing the trout

by electro-fishing and marking them. In the case of

the Big Horn trout, a hole is punched in the tail of

each trout.

A few days later, the same stretch of river is

electro-fished again. The biologists note how many

of the fish are marked in the total of all the fish

captured. A simple equation then can be used to make

the population estimate: the number of marked fish

in the second sample is to the total number of fish

in the sample as to the total number of marked fish

is to the total population. For instance, if there

were 100 marked fish in the second sample of 500 and

there were 500 total marked fish then the total

population would be 2,500 fish.

What happened was that the biologists marked very

adequate numbers of browns and rainbows on the first

pass. On the second pass, the biologists recovered

a statistically valid number of browns but not rainbows.

They were able to estimate that there were 800 browns

per mile in the upper river but could not make a

statistically valid estimate for the rainbows. Ken

Frazer told me that if he had to make an estimate,

it would be at least as many rainbows as browns.

Hence, 1600 trout per mile is a more realistic

estimate not the 800 that so many have posted

on the Internet.

As I stated earlier, there is a lot less trout

habitat in the Big Horn River due to the decreased

flows. The decreased flows also mean that the water

temperatures will average colder than when there is

a high flow year. In 2003, I never recorded a water

temperature in the upper river that exceeded 58

degrees. It wasn't until August that the temperature

warmed into the mid-50s.

Colder temperatures mean slower growth rates, not only

for fish, but for aquatic invertebrates as well. Hatches

that normally occur in early July don't begin until late

July or early August. Consequently, anglers who are

accustomed to fishing specific July hatches as yellow

Sallies or pale morning duns are out of luck if they

plan on fishing early in the month.

Another aspect of the low flows is that the habitat

for specific aquatic invertebrates has been diminished.

Species that require heavy riffles and large gravel or

cobblestone have declined in numbers. Over the past two

years, the yellow Sally and pale morning dun hatches

have been minimal to say the least.

Both black caddis and tricos have had sparse hatches

through the low flow years.

Mahogany duns, who were rare prior to the low flow

years, have burgeoned in numbers. The mahogany duns

are silt dwellers. Without heavy flows, silt deposits

have increased, particularly in the lower stretches

of the river where irrigation return waters are laden

with silt. Also, the plains streams flowing into the

river carry heavy loads of silt.

During the high flow years of the mid to late 90s,

scuds were relatively rare and sowbugs were numerous.

As the flows decreased the sowbugs followed suit while

scud numbers climbed.

Anglers had become accustomed to landing lots of trout

each time they fished the Big Horn. With fewer, but

bigger trout, anglers have had to settle for

considerably fewer trout landed per day's fishing.

However, anglers hook a fairly high number of trout

but the landing percentage is abysmal the large trout

are too big and powerful to allow a high landing

percentage. An expert fly fisher can expect to land

only about one half the trout he or she hooks; novices

probably will land less than one quarter.

The tried and true method of consistently catching trout

on the Big Horn is nymph fishing. While rainbows continue

to feed heavily on invertebrates throughout their lives,

browns switch to a fish diet. Anglers wishing to catch

more browns will have to change tactics in order land

the slab-sided browns. Of course, I am told "Streamers

don't work on the Big Horn except during the brown trout

spawning time." Maybe it is time to rethink this credo.

In the previous decade any pattern imitating sowbugs

would get the job done, but now scuds seem to have become

the go to fly. While the tan ostrich herl nymph has done

a great job as a sowbug imitation, it is also doing a

passable job of imitating scuds the tan herl with the

fire orange thread under wrapping gives a hint of orange

just as the natural does.

There are higher numbers of midges in the river

nowadays thanks to the silt deposits so midge

patterns are effective from early on, say March 1,

to the end of June. Some days the midge clusters

can be awesome to behold and to fish. The ideal

midge day is a cloudy, calm one a phenomenon that

occurs four to six times a month. When such a day

occurs, it is not unusual to see in the late afternoon

midge clusters the size of dimes floating down the

river.

Another aspect of the Big Horn River that I would

like to address is the crowds or lack thereof. In 2003,

the Big Horn had large numbers of anglers, particularly

on the weekends in April and May. Many of the anglers

came from points south, in other words, Colorado. As

the season wore on there were weeks where the crowds

were sparse and a person could fish the river without

seeing but a handful of boats. June and July were low

numbers months. August and September had a few more

anglers but at no time were the conditions crowded.

In October and November the river was close to deserted.

While the snow pack conditions aren't encouraging, it

is safe to say that the flow won't go lower than 1,500

cfs. If we have a wet late winter and early spring, it

might be such that the flow could be bumped up a bit

but I wouldn't hold my breath!

The Big Horn has settled down and should provide good

fishing for fairly large trout for several seasons to

come. This year there will be an influx of 12 to 14

inch browns and rainbows to compliment the large trout

in the river. However, the big fish will probably most

all die off this fall. Next year they will be in the 16

to 20 inch range and a good number of trout in the 10

to 14 inch range. Basically, the population will adjust

to the flows and will come into equilibrium with it.

When we finally have high flows, the first year will

be tough fishing because the lower number of trout

will be spread out over a large area. (Then, too,

the fish will have so much more feed that they will

grow at a geometric rate!)

Well, I hope I have helped to dispel some of the rumors

about the Big Horn River and I hope, too, that you will

try fishing it again. All you will have to do is to

relax and go with the flow. ~ Bob

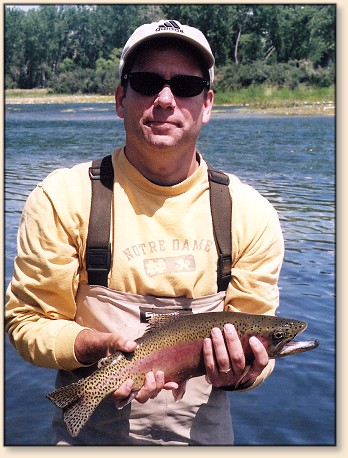

About Bob:

Bob Krumm is a first-class guide who specializes on fishing the Big Horn River in Montana,

(and if there terrific fishing somewhere else he'll know about that too.) Bob has

written several other fine articles for the Eye Of The Guides series. He is also

a commericial fly tier who owns the Blue Quill Fly

Company which will even do your custom tying! Bob is a Sponsor here! You can reach him at:

1-307-673-1505 or by email at:

rkrumm@fiberpipe.net

|