|

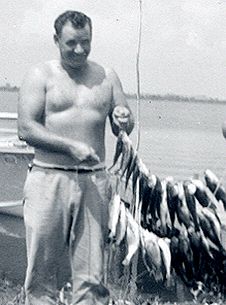

My dad wasn't a fly fisherman, but he was an

avid outdoorsman.

The overwhelming majority of my adolescent memories

are firmly planted outdoors -- hunting, fishing,

crabbing, trawling. Our excursions were always

in or near water, and more times than not, at least

one of the multiple boats we owned at any given

time was built in our backyard.

As a child, when asked for my address, I was often

tempted to tell the inquirer where our camp was

located near Lake Salvador, since we seemed to

spend more time there than home. But I knew what

they meant, so I suppressed the mischievous urge.

We broke the silence of many a pre-dawn morning

with the drone of an engine, wrapped in layers of

insulated clothes against the biting cold, as we

plied toward duck blinds. Or enjoyed the coolness

of the air that can only be found in the early morning

hours of an otherwise blistering summertime, laden

with rods, reels and tackle, a shrimp trawl or

possibly stacks of crab lines.

It was an idealistic childhood in the vast wetlands

of Cajun country. But I was too young and naive, and

having too much fun, to realize that as much as we fished, our

lives were void of a higher calling -- fly fishing.

That's not to say fly fishing was unknown to my dad.

One of my earliest memories was the discovery of a

long, two-piece green rod with a funny-looking reel

propped in the corner of a hall closet. It was a

fiberglass fly rod, from the Sears & Roebuck catalog,

that dad simply called a waste of time and money.

"Too much line to mess with."

He, like most men of his generation, was a meat hunter.

He enjoyed the sport of fishing immensely but couldn't

fathom such concepts as catch and release, so efficiency

was of the highest concern in the selection of all

fishing tackle. These were the days before size and

creel limits; success was gauged by full ice chests,

not the number of fish. Our reels were spooled with

heavy line, and our freezers never lacked for an

abundance of seafood and game.

Time with my dad on the water was priceless. And even

though we were both "quiet" fishermen, rarely speaking

as we made our casts, I was constantly exposed to decades

of experience, soaking in every bit of knowledge.

His years in the marsh had taught him when and where

to find the fish, and what techniques to use; lessons

handed down from his dad.

As a child, I was always amazed at how he could make

dozens of turns in the seemingly endless marsh and

find his way back, even though the miles of broken

land looked the same to my young eyes. As a guide,

I get to relive that wonder as out-of-state

clients, not accustomed to such expanses of marsh,

constantly scan the panorama forclues to our location.

The look is unmistakable, and it's the one time when I can

actually read someone's thoughts: "You do know the way

back, right?"

Sometimes, they will actually verbalize the question.

It's delivered tongue-in-cheek, of course, but deep down,

I can tell a positive answer would be reassuring.

I can't blame them. The marshes of southeast Louisiana

are massive, spanning as far as the eye can see in

every direction, and beyond. It's been more than 30

years since my first trip into the marsh -- fishing

pole in one hand and a can of worms at my feet,

watching dad twist and turn our boat through the

aquatic labyrinth -- yet I still haven't seen all

of it. I was not only blessed with a wonderful dad,

but also with one of the world's greatest estuaries

as my playground, my backyard, my home.

My transition as a fisherman through the years was

rather typical. On my first trips, I just wanted to

catch a fish. Then I wanted to catch a lot of fish.

Later, as the desire to catch bigger fish became

stronger, the pursuit of trophy-size specimens

became more important than filling a limit. Eventually,

even something as inconceivable to my dad as catch

and release started to make sense.

I still enjoy many a fish dinner, but now I fish for

the pleasure of the sport. If my freezer is well-stocked,

I release my quarry with gentle care and a smile, hopeful

that we will meet again another day. Most of my clients

are the same, only wishing to return to the dock with

photographs of their catches and heads full of memories.

Occasionally, a client will ask me if I'd like to keep

a few of the fish for myself. Often, I will accept a few,

which I bring to my mom.

She loves fish. And the concept of catch and release

is lost on her, too. I can only bring fish to my mom

now since dad is no longer with us. And sadly, we

lost him years before he left this earth -- his mind

and memories stolen by Alzheimer's. Dad never got to

see me fly fish. I began learning the art before his

body succumbed to this world, but not before his mind

was ravaged by this cruelest of diseases.

As my mom told me on the day of his funeral, "He died

a long time ago. We were just taking care of his body."

I wish dad could have watched me fly fish, for the

same reason I beamed as he watched me reel in my first

tiny bream. No matter our age, we want to show our dads what

we learned, what we accomplished, and we want to see

that smile that lets us know he couldn't be more proud.

If he had been granted the mind to comprehend in his

last years, I'm sure he would have approved of my

transition to fly fishermen.

But he still wouldn't understand catch and release.

~ Marty

About Marty:

Capt. Marty D. Authement owns and operates Marsh Madness

guided fishing service in Houma, Louisiana. He is also Lifestyles

Editor of his hometown newspaper, The Courier. He can be

reached at, captmarty@internet8.net

or visit his Web site at www.marshmadness.net.

|