|

Have you ever noticed how some of the best times out

begin with a weekday drive up the mountain? Feeling

better than you did playing hooky as a kid, it means

a nice, relaxed drive you can actually enjoy. Light

traffic. You can contemplate the scenery in peace.

And there is the expectation of the road ending at a

gate that's been locked for the season and a good mile

or so from the nearest trailhead. Beyond that, well. . .

There's always an ulterior motive for things of this

nature, isn't there?

My sneaking hunch is that most fishing destinations begin

their existence as a scheme hatched in the quiet backwaters

of our minds. You know how it works: For no specific

reason you find yourself with the niggling itch of an

idea, one that comes on slow and sweet like the whisper

of a hidden Shangri-La where untouched trout are holed-up

in some mysto mountain stream.

Day and night it grows on you, eventually forming a vision

of the perfect spot -- an idyllic stretch of water where

the Big Ones quietly fin their time away. Perfection

in the land of the wild things.

Of course, we've all got an opinion as to just what perfection

is. The itch that gets me, for example, leans toward

scenery-heavy locations offering solitude and fish that

rarely see the likes of me or any other fisherman. This

may or may not include one of my fishing buddies, and

the fish may or may not take a fly as readily as I'd

prefer. That's a given, and part of the challenge.

But it definitely does not include strangers walking

up to me uninvited when I'm working a fish and chucking

out two-and-a-half pounds of lead tied off below a treble

hogged-up with corn, marshmallows, or some other

fluorescent-colored, dough-ball substance.

A while back -- after a particularly aggravating session

at a small reservoir lake where everyone, and I mean

everyone, was hauling them in except me -- I got the

itch real bad. I'd even begun to seriously consider

the argument for the sub-fifteen dollar rod-reel combination,

at the same time wondering why I wasn't man enough to hook

up with a corn kernel from a pile someone had left on

the ground. (All in the pursuit of scientific enlightenment,

you understand.) Instead, I called it a day and dragged my

butt back to the car. A rough day when you can't interest

a tank fish. Tougher still when you admit it to others.

Then it hit me: I'd seek out and fish places that were

too remote, too inaccessible for the

twelve-pack-and-a-lawn-chair crowd to get into, or to get

back out of should they manage to stumble their way in.

Not only would it be the perfect spot, it would be the

perfect, secret spot.

Of course, logic just had to soberly point this out as an

indulgent fantasy -- that if I could find my way into such

a place, it would stand to reason that others would be able

to, and most likely already have. But imagination -- where

the idea for the perfect spot came from in the first

place -- rapidly countered with excuses, each better than

the last and all designed to prolong my stay in the land

of the wild things.

Sadly, logic began to win out. Not because I was in agreement,

but because regardless of how good it sounds, most activities

that a guy actually intends to participate in have to take

place somewhere.

Imagine, now, that you live in the arid Southwest where water

is less than abundant -- a place where the existing resource

is finite and in high demand.

Depending on where you stand along the political fence (think

barbed wire here), the battle for water rights in these parts

can be divided into two highly polarized camps.

Camp one seems to view water as nothing more than a raw

commodity -- liquid real-estate open for rampant deal-making

and development. A thing you can dip into, suck short-term

profits from, then cut and run before the ecological fallout

catches up with you. Never mind that this mentality is

guaranteed to turn first-order waters into third-rate

irrigation ditches at best.

On the other side of the fence we find camp two. Camp

two -- fervent in the belief that our waters possess a

near-mystical quality -- views water as a spiritual treasure,

healer of the psyche, giver of life, and just about the only

holy thing keeping us from rampant, dust bowl anarchy.

No way, no how is it something that we should allow to

be mucked-up by carpet-bagging, greedy sons-of-bitches.

A profoundly soulful sentiment, and one to consider deeply.

Pick a spot just about anywhere between these two camps,

and you'll find plenty of others jockeying for the same

piece of pie.

This can make for some crowded water.

If you're a fisherman whose proclivities are aligned somewhere

to the East of camp two but faring to the West side of middle,

it's enough to irritate you more than putting your foot into

a shoe full of scorpions.

And so it goes. . . As for the idea of the perfect spot,

logic continued to rant on with a big negatory, finally

stinging me with the equivalent of a bent alder branch

in the face. Dreaming was fine, but what about making

good on reality?

Well. . . What about reality? I felt an uncomfortable

twinge of panic, and had to admit that a guy just might

want to scale things down a bit. After all, it would be

nice if the perfect, secret spot were accessible from home

so that you could actually go and fish the place from

time to time.

Fortunately, even in this land of scant rainfall and tortuous

summer heat, you can still find places where relatively

untouched waters flow. Quiet, secretive places where the

water is nothing more than what it is. Places you must

either discover on your own or have the location entrusted

to you, usually by a close friend who will make you swear

in blood never to divulge the secret to another. Like the

promise of an X on a treasure map, these places can grip

the imagination with little more than a vague comment

overheard, or chance reference found in an old journal.

But they only become reality when you explore the

convictions of your belief and put forth the effort

to discover them.

To be honest, I'd seen places of the like before. They'd

been interesting enough in passing to make me wonder about

their potential, but it seemed like each time I came across

them I'd been locked into other plans or trying to make time

between one destination and another. I had no idea if they

harbored fish or not -- but it had come time to find out.

So I began doing the legwork. I learned to keep my mouth

closed and to listen carefully, picking up scraps of

information from a good many unlikely sources, and some

likely ones that might not otherwise have been so cooperative.

I took an interest in topography and read between the lines

in the forest service literature. Weekend hikes became

scouting missions where I walked a lot of stream beds

(some that were dry and others that might as well have

been). In general, I started paying my dues.

Eventually, I discovered a quiet little place that can,

at times, come close to perfection. The kind of place

you fish just often enough -- not so much so as to spoil

the purity of the experience, but enough to remember why

you went looking for it in the first place. And though

it may not be a secret to everyone, it's easy enough to

convince yourself that it is.

The last time I was up there was late fall. Too early for

snow, but far enough along in the season that the air was

crisp, and cold enough for a light haze of frost on the

ground. And a sweet drive up. Light traffic. Beautiful

scenery. A gate at the end of the road locked for the

season. . .

There was another car parked near the gate, and while I

busied myself with tucking the pack rod, reel, and flies

into a knapsack, I wondered about its owners. Hikers,

most likely -- at least I was hoping so.

Trying to look more like another hiker than a fisherman,

I shouldered my pack, moved around the gate, and began

following the road toward the trailhead.

Trying to look more like another hiker than a fisherman,

I shouldered my pack, moved around the gate, and began

following the road toward the trailhead.

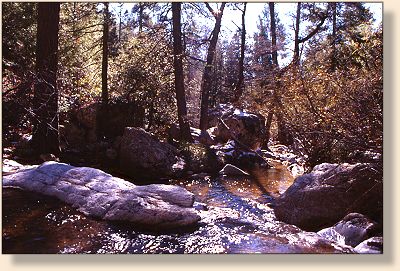

With blue sky overhead -- blue in that dense, hyperreal

way it often is over the desert -- and gravel crunching

underfoot, I began to notice a casual ratcheting down

of the low-grade urgency that seems to accompany too

many things in life.

I don't recall this happening very often at the local

park-n-cast. The morning light hung translucent in the

pine needles, causing them to glisten as if from some

internal radiance. Things felt right with the world.

And, I was going fishing.

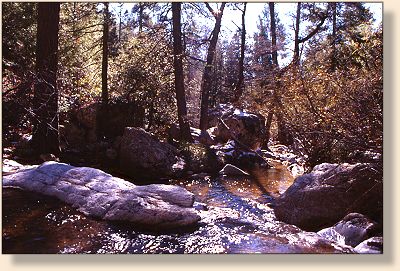

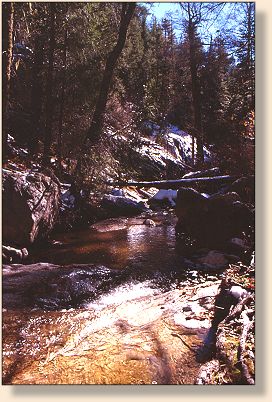

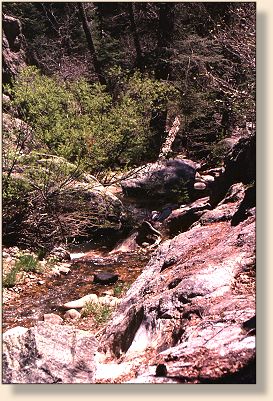

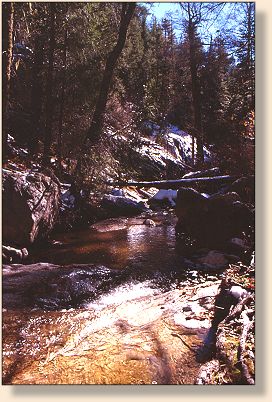

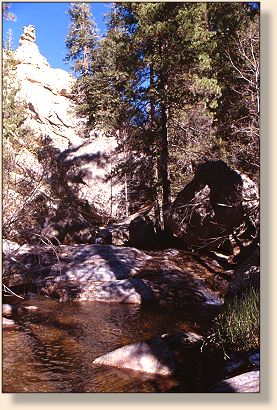

From the main trailhead you can sight a good ways down

the length of the canyon; winding along a fold in the

mountain range, it will ultimately open up five or six

thousand feet below into the desert bajada. Within its

granite-walled confines, the canyon supports a healthy

population of hoary old pines, some of them sprouting

from clefts in the canyon walls. Various willow, alder,

and other deciduous trees follow the waterline and

provide a good balance to the forest coverage. Hidden

at the bottom of this is the stream. From here it is

nothing more than a teasing sparkle that winks at you

from an open space before disappearing beneath the

greenery. But it's enough to lead you on.

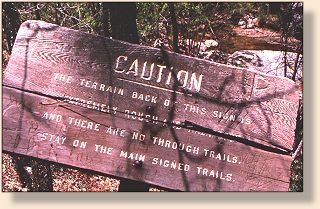

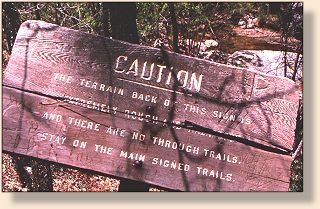

From the main trail, a lesser-used fork pitches downward

on a rambling course toward the canyon bottom. By rambling,

I mean that the trail deteriorates into a scraggly run,

barely recognizable as a path weaving you over treefalls,

around clustered boulders, and into thorny brush housing

an unknown congregation of spiders, snakes, and other

beasties.

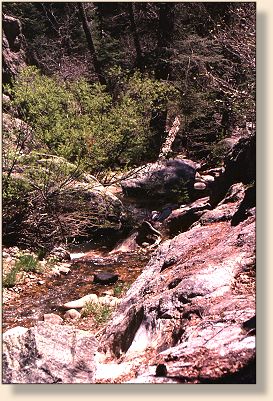

A tassle-eared Albert's squirrel and some unseen birds

cackled at my progress down to where the stream slips

along the canyon floor while, above, the wind soughed

over a ridge, carrying with it the smell of Ponderosa

pine and frosty earth.

A beautiful place, but savage in its finality. I'd been

told by forest rangers that to get hurt down here would

be, at best, unpleasant. Doubtful, said they, that anyone

would happen along to carry me out. And, since I'd gone

off without leaving any message as to my whereabouts, no

one was bound to come looking for me. Not necessarily

the smartest thing to do. But I was here and no reason

to cry about it.

A beautiful place, but savage in its finality. I'd been

told by forest rangers that to get hurt down here would

be, at best, unpleasant. Doubtful, said they, that anyone

would happen along to carry me out. And, since I'd gone

off without leaving any message as to my whereabouts, no

one was bound to come looking for me. Not necessarily

the smartest thing to do. But I was here and no reason

to cry about it.

Now there are those who would question the very notion of

being down here in any capacity, let alone by one's lonesome.

Without a cell phone. Without a global positioning system.

Without the miracle of technology. What, they might ask,

would I do if I took a fall and broke a leg or cracked

my skull?

Good question. I imagine I'd work my way through it. At least

I was aware of the rules down here.

There's a distinct sense of place in all this wildness,

and you come to accept the implied danger that goes along

with it. Here, there is no question as to the consequence

of a misstep. Here, you know precisely where you are on

the earth -- in a place where actuality takes on the

dreamwalk presence of the spiritual. A place untouched

by the notion of bottom line numbers, site hits, or any

of the other ways used to measure success. And there

is also the sense of exhilaration that comes with being

alone out in the Great Big -- a buzz of contentment that

makes life all the more vivid and precious. In fact,

one of the reasons for being out here is to get away

from the marvels of the electronic grid and return to

something more resembling the basic human self.

Nearing the stream, I mentally shifted gears with the

sound of flowing water. I began to wonder if I'd be

fortunate enough to make a connection with some of

the wily trout living in these waters.

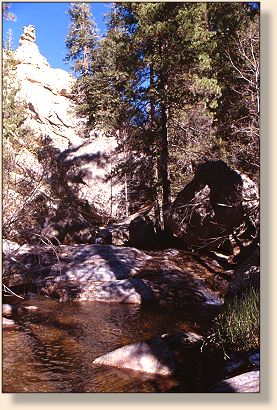

The fishable water in this stream spans an elevation

of about a thousand vertical feet or so. Within that

reach, the fish, bronze to olive colored browns that

were introduced long enough ago to have forgotten

their hatchery past, tend to hold in the deeper pools

or lurk beneath the cover of rock shelves and accumulated

deadfall.

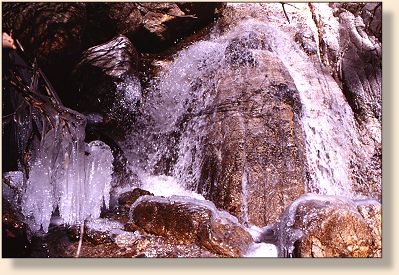

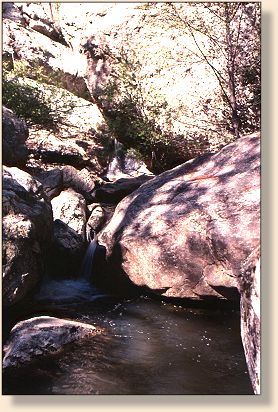

The water has a light tea coloration, and is almost

golden when the sun strikes it just so. When it's

running low, which is a good portion of the time,

you can jump across the stream in most places.

However, just one look at the debris caught in some

of the tree branches makes it more than obvious that

this can be a raging torrent in wet times. Not a

good place to be caught in a thunderstorm.

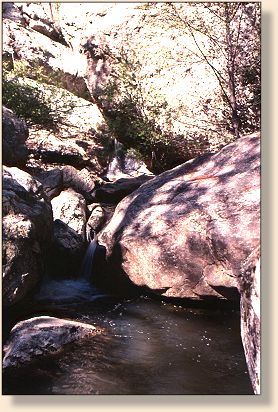

There's something hypnotic in the sound of the water

reverberating against the canyon walls here. More

than once I found myself catching my breath to listen

for what I thought were voices. As the stream glides

along the canyon bottom, it spills over polished

outcroppings of granite, quartz, and feldspar and

falls into unexpected pools where the fish hold,

seeming to conjure an ancient, peripheral sense of

deja-vu, like some ancient gene memory risen to

the surface.

With a gathering sense of place, I found myself

comparing this experience against the drive-up

mentality of easy-access days spent hammering the

water and keeping score as if fish catches were

body counts to be tallied and filed away on some

ledger.

I found myself wanting to share this moment with others.

But there is a certain fragility in such places that

forced me to reconsider. Thoughts of paying one's dues.

Of becoming aware of one's presence in the world. Of

showing respect. And of the need to discover something

infinitely greater than myself on my own.

As I meandered on down toward the fishable water, I was

visualizing my first cast. Then I saw it -- a ragged,

derelict t-shirt on the ground. The spoor-sign of

encroaching civilization and trash culture. Logic

whispered "I told you so," but I shut it out and continued

on. I'd pick up the filthy thing on the way out.

Deeper in the canyon, the air, through some trick of

light and shadow, seemed to carry the presence of an

individual entity. Initially, I tend to get unnerved

by this kind of solitude. But it's just a momentary

thing having to do with a quiet fear that comes on when

leaving the beaten path -- the fear of being tracked or

followed, of being alone out in the Great Big. An anxiety

brought on not by the prospect of confronting a mountain

lion or bear, but rather with the possibility of

encountering some random individual having less than

human motivation. But this passed quickly, shed in

silence like the outer jacket that is no longer necessary.

Deeper in the canyon, the air, through some trick of

light and shadow, seemed to carry the presence of an

individual entity. Initially, I tend to get unnerved

by this kind of solitude. But it's just a momentary

thing having to do with a quiet fear that comes on when

leaving the beaten path -- the fear of being tracked or

followed, of being alone out in the Great Big. An anxiety

brought on not by the prospect of confronting a mountain

lion or bear, but rather with the possibility of

encountering some random individual having less than

human motivation. But this passed quickly, shed in

silence like the outer jacket that is no longer necessary.

I neared a pool that had always been productive. But,

wary as these fish are, they'd probably already felt the

vibration of my footsteps through the stream bed. I

unshouldered the knapsack and took out my gear, knowing

that if another person came along I would ditch my equipment

behind some rock or fallen log so as to veil my purpose

and the existence of the trout.

Assembling my gear, I thought about how these fish spend

most of their time hiding under boulders and logjams.

I've seen a trout spook from the edge of a pool no bigger

than my bathtub and then disappear under I don't know what.

I'd also seen them freeze in place, with not even a gill

plate moving, pretending to be sticks on the bottom.

For each holding area of water I'd get one, maybe two casts

before I spooked the pool. If this didn't draw a fish out

from beneath a rocky ledge or twisted logjam then I may as

well tip my hat to their canniness and move on. I'd

consider myself lucky just to entice a fish into looking

at a fly, let alone convincing one to rise to it.

Creeping up to the pool, I could not help but think that

here these fish are, living close to the bone in this magic

place. Living good when the water is high and hunkering

down in the mean season of summer drought.

I wondered how they survived the lean summer months when

the lifeblood water thinned to a trickle and the shrinking

pools grew progressively warmer. Were there underground

streams and channels they migrated to? Or did they survive

by some other mystery? Were the secretive shapes that

occasionally darted from view the only residents here?

Or were their numbers greater than I imagined, hidden

somewhere within narrow caverns beneath the stream bed?

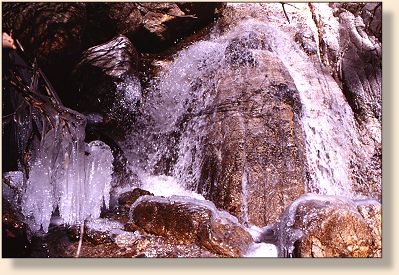

As these impressions flowed through my mind and hovered

at the edge of consciousness, I casted to a pocket of

water tucked behind a small waterfall. That's when

I felt what I'd been seeking, that magic instant of

connection where you have become more of a place than

you are a physical being within it. The fly was

alighting right where it wanted to be. And, with

a clarity born of standing ankle deep in the holiest

of waters, I was at that place where one reality may

perchance meet another and break through the meniscus

tension of separation like a wild trout flaring out

of the water, however slightly, to touch a surface fly.

~ Daniel Fryda

|

Trying to look more like another hiker than a fisherman,

I shouldered my pack, moved around the gate, and began

following the road toward the trailhead.

Trying to look more like another hiker than a fisherman,

I shouldered my pack, moved around the gate, and began

following the road toward the trailhead.

A beautiful place, but savage in its finality. I'd been

told by forest rangers that to get hurt down here would

be, at best, unpleasant. Doubtful, said they, that anyone

would happen along to carry me out. And, since I'd gone

off without leaving any message as to my whereabouts, no

one was bound to come looking for me. Not necessarily

the smartest thing to do. But I was here and no reason

to cry about it.

A beautiful place, but savage in its finality. I'd been

told by forest rangers that to get hurt down here would

be, at best, unpleasant. Doubtful, said they, that anyone

would happen along to carry me out. And, since I'd gone

off without leaving any message as to my whereabouts, no

one was bound to come looking for me. Not necessarily

the smartest thing to do. But I was here and no reason

to cry about it.

Deeper in the canyon, the air, through some trick of

light and shadow, seemed to carry the presence of an

individual entity. Initially, I tend to get unnerved

by this kind of solitude. But it's just a momentary

thing having to do with a quiet fear that comes on when

leaving the beaten path -- the fear of being tracked or

followed, of being alone out in the Great Big. An anxiety

brought on not by the prospect of confronting a mountain

lion or bear, but rather with the possibility of

encountering some random individual having less than

human motivation. But this passed quickly, shed in

silence like the outer jacket that is no longer necessary.

Deeper in the canyon, the air, through some trick of

light and shadow, seemed to carry the presence of an

individual entity. Initially, I tend to get unnerved

by this kind of solitude. But it's just a momentary

thing having to do with a quiet fear that comes on when

leaving the beaten path -- the fear of being tracked or

followed, of being alone out in the Great Big. An anxiety

brought on not by the prospect of confronting a mountain

lion or bear, but rather with the possibility of

encountering some random individual having less than

human motivation. But this passed quickly, shed in

silence like the outer jacket that is no longer necessary.