It is unknown who actually conceived the idea of

a bulbous head made from clipped deer hair,

although the American Don Gapen certainly gave

the technique currency with the introduction of

the Muddler Minnow in 1937. Writing in 1940, William

Bayard Sturgis said that the idea of hair bodies

could have been brought to Chicago around 1912 by

Emerson Hough, who stated that he had first seen

flies tied that way on a fishing trip to the far

north of Canada.

It would seem that in Australia, deer hair as a fly

dressing material, was not used until the late 1950's.

In 1959 two well-known fly-fishermen and fishing

authors, Joe Brooks from America and David Scholes

from Australia river-fished together in Tasmania,

the island state south of mainland Australia. Joe

fished a Muddler Minnow (Don Gapen) and David probably

fished local patterns, perhaps a Matuka or a Wigram's

Robin (Dick Wigram). Scholes was not terribly impressed

with the Muddler Minnow in the beginning, this was

because it didn't resemble any Australian minnows. It

wasn't until 1964, when he fished backwaters on the

Meander River with Jim Boswell, another visiting

American angler, that David's eyes were opened to

the true value of the Muddler Minnow. Jim took four

trout with the Muddler when David couldn't land any.

A year or two before Joe Brooks introduced the Muddler

Minnow itself, the Missoulian Spook (Dan Bailey), had

already made its Australian debut. Essentially the

Missoulian Spook is a cross between Don Gapen's Muddler

Minnow, made using white deer hair and the Bumble Puppy

(Theodore Gordon), a chenille-bodied streamer. Bailey

called it the White Muddler Minnow and it was renamed

the Mizzoulian Spook by Vince Hamlin, the author of the

"Alley Oop" comic strip. Both spellings have been used

ever since.

In Australia back in those days, information about

new flies and dressing materials mostly came from

books, visiting overseas anglers and word-of-mouth.

In his 1961 book, Fly Fishing in Australia

David Scholes informed Australian anglers of the

Muddler Minnow.

A few Australian fly tiers began making the Muddler

Minnow and a tackle shop imported some Muddlers from

the USA. Interestingly, those first imported Muddlers

were accidentally tied on extremely light hooks and

anglers couldn't sink them. Perhaps some of those

flies may have been used as grasshopper imitations.

In the summer of 1962, Dušan 'Dan' Todorivic and Wolf

Duwe were on a fly-fishing trip on the Murrumbidgee

River around the delightful fly-fishing waters of the

Snowy Mountain region near Adaminaby and Bolaro in New

South Wales. Fly-fishers were scarce in those days and

grasshopper fishing, to those who didn't fly-fish, was

practiced by flicking a live grasshopper upstream using

a general-purpose fishing rod. The problem was that

they couldn't cast the hopper far and very often, the

casting action would flick the hopper off the hook.

Anglers began using longer rods, some even used fly-rods

so they could cast longer distances. Of those who used

fly-rods, many later went on to become true fly-fishers.

Fishing a live hopper with a fly-rod still didn't solve

the problem of the hopper flicking off the hook and a

good supply of live hoppers was always required. Instead

of madly running around trying to catch live hoppers,

some anglers would spread a fluffy woolen blanket on

the ground and herd hoppers onto it. The raspy legs of

the grasshoppers would become entangled in the fluffy

wool fibres. Another method was to simply herd hoppers

onto the water where they could easily be collected

from the surface.

I digress. Back to our true fly-fishermen, 'Dan'

Todorivic and Wolf Duwe, fishing the Murrumbidgee River

in 1962. The large grasshoppers common to that area,

Kosciuscola cognatus and Kosciuscola

usitatus, were abundant, but using the

standard hackled hopper patterns of that era (sizes

10 and 12), they were only having moderate success.

After a few days, fed up by their inadequate catch

rate, Dan began experimenting at the fly vise.

Dan ingeniously created a new grasshopper pattern.

He had used yellow chenille for the body, golden

pheasant tippets for an underwing, with a very

narrow section of mottled turkey wing on each side

of the pheasant tippets. To imitate the red grasshopper

legs he utilized dyed-red hackles with the fibres

trimmed close to the hackle stems. Dan had some

deer hair in his tying kit; perhaps he had been

using it to make Muddlers. He knew that deer hair

floated so, instead of a normal hackled fly, Dan

tied a Muddler head on his new grasshopper, which

they called Dan's Hopper.

As a hopper pattern with a spun deer hair head, the

Letort Hopper is just a bit older, having been

designed by the Pennsylvania fly fisher Ed Shenk

sometime in the period 1958-60.

Letort Hopper tied by Ed Shenk, photographed by Hans Weilenmann

Anyway, the trout loved Dan's new pattern; its

success rate compared to that of the hackled hopper

was extraordinary. The new fly, sat low on the water,

much more like a natural hopper. The fly's success

was attributed to this low profile. It wouldn't have

taken them long to find out that if they landed the

fly on the water with a bit of a thud like a real

grasshopper, it would still float and if they

crash-landed the fly it would often attract trout

forthwith.

Dušan 'Dan' Todorvic was a semi-professional fly tier

and, with his fly-dressing partner, Tom Edwards, began

making the fly commercially.

In summer throughout southern Australia, grasshoppers

become very abundant, some years much more so than

others. Dan's Hopper was so good that it soon became

a popular fly. Some who fished live hoppers even took

to using the new artificial hopper. It was almost as

good as the real thing, with the advantages of not

having to catch live hoppers and, the bait wouldn't

flick off the hook.

Also, grasshopper fishing is very forgiving and those

learning to fly-fish could more easily achieve success.

Compared with normal fly-fishing, where the presentation

is usually delicate, with grasshopper fishing you can

mess up the cast to some degree and land the fly

heavily but still catch fish.

In August 1972, Tom Edwards wrote in the Victorian Fly

Fishers Association newsletter: "The Birth of the Nobby

Hopper." In the article, Tom clarifies how the name change

from Dan's Hopper to Nobby Hopper came about. Tom explains

that Fred Stewart, the famed Australian fly-fisherman,

commented whilst talking to Bob Rolls, "This fly is more

of a Nobby Hopper than a Dan's Hopper." From that time

on the name Nobby Hopper stuck.

In Tasmania, David Scholes and Noel Jetson wanted

something smaller because Tasmania doesn't have the

hordes of large grasshoppers which occur in New South

Wales and parts of Victoria. Mind you, the Nobby Hopper

is still a useful fly in Tasmania. Noel simplified the

tying and produced a smaller version which was

immediately christened Noel's Nobby Hopper by David

Scholes.

Noel's Nobby Hopper

Dan's Hopper, or the now called Nobby Hopper, made it's

way to South Africa. As in Tasmania, the pattern was

too big to represent local hoppers. A resourceful South

African fly dresser made the fly smaller, but there was

one important change to the legs. He put a knot in the

legs making that dog-leg or grasshopper-leg shape, now

commonly associated with many hopper patterns. It was

found that this method of tying the legs had two important

attributes. First, the legs acted like outriggers, making

the fly more stable on the surface. Second, from an

anglers and a fish's point of view, it was much more

realistic. The two red legs poking into the surface

at the rear end of a hopper seems to be a powerful

trigger used on many of today's successful hopper

patterns.

The South African version, with its knotted legs, made

its way back to Australia. It was discovered in a

Melbourne tackle shop by Andrew Braithwaite. Andrew

re-introduced it to David Scholes as the South African

version of the Nobby Hopper.

From fishing with Joe Brooks and writing about his

first encounter with the bulbous headed Muddler,

developments had come full circle, and, as fate

would have it, much like a boomerang coming back,

a great little grasshopper fly had returned to

David Scholes.

Grasshopper fishing

Grasshoppers mate in late summer and autumn, after

which the females deposit their eggs in soil. The

eggs remain dormant throughout the winter and hatch

in late spring as worm-like larvae which, soon become

small grasshoppers without wings. It takes about seven

weeks and five moults or growth stages for the

grasshoppers to reach adulthood.

Gradually, as the height of summer looms, less aquatic

food is available in lowland rivers and trout start

relying more and more on terrestrial foods,

particularly grasshoppers.

The hotter the day, the hotter the hopper fishing becomes.

However, a slight wind is advantageous. An old trick,

when hoppers are plentiful, is to alarm grasshoppers,

causing them to hop or take flight. Using the wind

coming from an appropriate angle behind you as you

fish your way up a river, you can panic and herd

live hoppers onto the water. This maneuver is even

better when two anglers work together; one fishes

whilst the other herds hoppers onto the water. When

alarmed by herding, hoppers that can't fly, flee

haphazardly in all directions away from the herder.

In the rush to escape they often miscalculate their

trajectory, placing them on a collision course with

the water, particularly if blown by wind. The number

of wingless hoppers accidentally ending up on the

water vastly outnumber winged hoppers.

If trout can remember, then one of their favorite

memories must be grasshoppers. Once hoppers are

herded onto the water they are a great temptation

which, even the most stubborn trout seem unable

to resist. Usually, if not spooked, they will rise

to live hoppers with gusto. Rising trout are telling

you exactly where to cast your imitation, in most

cases a bit upstream of the rise. If the trout won't

rise, as you progress up a stream or river, you can

induce a trout by making casts to likely looking spots.

Be it either learnt of instinctual, trout seem to know

about hoppers and the splat one makes hitting the water.

They clearly love eating them, so just keep casting,

sooner or later one won't be able to help itself. Expect

a sudden violent take.

On the wider sections of a river, flying hoppers will

often turn back when they find themselves flying over

water. This appears to be because they can only fly a

short distance. Those that attempt to make it to the

other side will constantly lose altitude. As they do

so, some inevitably crash onto the surface well out

into the stream or near the far shore. The large

yellow-winged locusts are the best fliers they can

easily fly across the widest river. Nevertheless,

some still end up on the water, especially in the

morning when temperatures are not high enough for

maximum activity of cold-blooded insects.

When a good offshore breeze is blowing, hoppers may

be herded onto a lake or pond using the same technique

as for rivers. This manner of fishing is generally

best over deep water near the shore.

Once on water, hoppers are virtually helpless. Those

that end up on the water early in the day before their

metabolism warms up are less likely to attempt to swim;

nevertheless, if fishing an artificial hopper, a slight

twitch of the rod tip, every now and then, is enough

to suggest movement and trout are more prone to be

attracted to a struggling kicking hopper.

The common Australian wingless grasshopper Phaulacridium

vittatum found throughout southern Australia and New Zealand

Trout feeding well out are generally taking winged

hoppers; those feeding closer to the shore are usually

taking the smaller wingless hoppers. Although they may

be reluctant to feed in shallow, clear water, such

opportunistic feeders often zoom up from the depths

to engulf a hopper.

Be warned, usually at this time of year and throughout

summer, the rivers can become so clear that the trout

become extremely cautious and flighty, especially on

bright, still days. Trout perceive they can easily be

seen by predators in sunny weather, therefore they

will look for cover overhanging brushes above the water,

undercut banks, drowned trees, riffles, deep runs, or

pools. It is essential to keep as far back from the

water as possible, keep your profile off the skyline

and your shadow off the water, stalk slowly and

endeavoring not to be seen. If herding hoppers onto

the water, it is a balancing act between stealth and

herding, depending on wind strength. Most trout,

including larger specimens, will reveal their

feeding station when a steady stream of live hoppers

is temptingly drifting overhead.

As the wind and the summer sun dry the fields, grasses

take on a bleached straw-and-brown coloration. At the

same time, in harmony with the plants, grasshoppers

also change their camouflage pattern. As the fields

dry, food becomes scarce and grasshoppers seek out

the green plants along the riverside. The rocky areas

between where the grass margin stops and the actual

water begins, holds little attraction for grasshoppers,

simply because there isn't much food or concealment

from predators. Shrewdly, the best places to cast a

small artificial hopper are beside or just downstream

of a steep grassy bank over deep water or where grass

or tussocks are present very close to the river edge.

Look for shaded areas where trout feel safe and wingless

hoppers are likely to blunder or be blown onto the water.

On flat sections of rivers, grasshoppers generally don't

sink. However, on fast-water stretches they are soon

swirled beneath the surface and in these areas trout

will often take an artificial grasshopper sub-surface.

Materials List: Nobby Hopper (Dušan 'Dan' Todorivic)

Hook: # 10 – 12 down-eyed, dry fly hook.

The hook used in the photo is a Mustad 94840.

Thread: Clear or black Gudebrod G.

Body: Yellow chenille.

Underwing: Golden pheasant tippets and

mottled turkey wing.

Legs: Dyed-red, stiff hackle stems with

fibres trimmed close to stem.

Head & Collar: Natural deer body hair.

Tying the Nobby Hopper

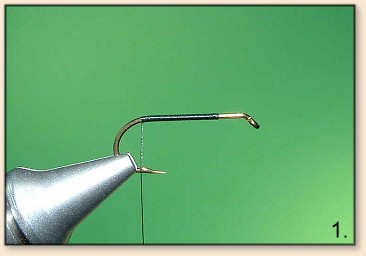

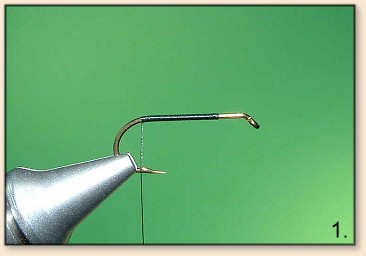

1. Place hook in vise and start thread about a

quarter of the shank length behind the eye. Wrap

thread down shank to bend.

1. Place hook in vise and start thread about a

quarter of the shank length behind the eye. Wrap

thread down shank to bend.

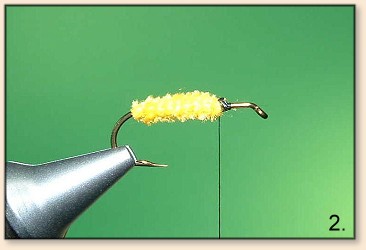

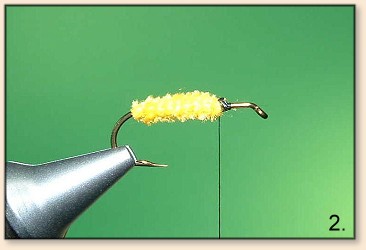

2. Tie in yellow chenille and then wrap thread

forward to the starting point, a quarter shank

length behind the eye. Now wrap chenille body.

2. Tie in yellow chenille and then wrap thread

forward to the starting point, a quarter shank

length behind the eye. Now wrap chenille body.

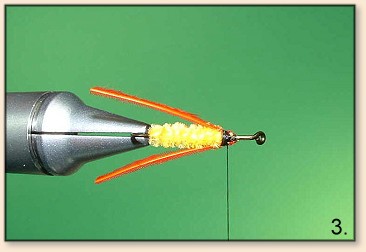

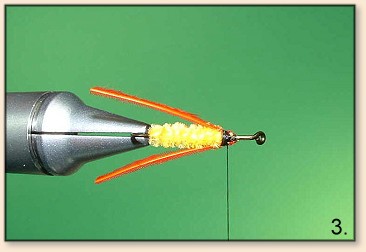

3. Prepare the legs by trimming the fibres of

two dyed-red cock hackles close to the stems. The

tip of the stem is tied in at the shoulder one on

each side. The thicker part of the stem is cut so

it protrudes about a quarter of the shank length

past the bend.

3. Prepare the legs by trimming the fibres of

two dyed-red cock hackles close to the stems. The

tip of the stem is tied in at the shoulder one on

each side. The thicker part of the stem is cut so

it protrudes about a quarter of the shank length

past the bend.

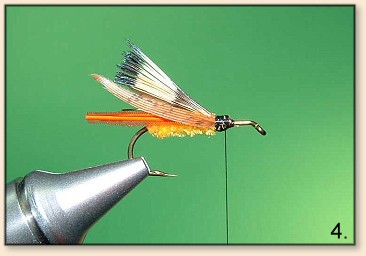

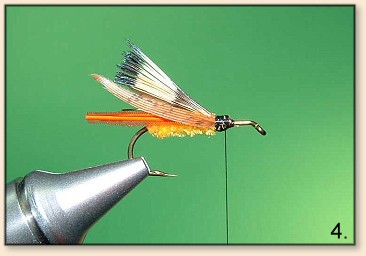

4. Tie in a bunch of golden pheasant tippets,

shiny side down. They should be about the length

that, if they were pushed down, they would reach

the bend. On either side of the pheasant tippets,

tie a thin strip of mottled turkey wing a little

longer than the pheasant tippet about the length

that, if pushed down, they would almost reach the

end of the legs.

4. Tie in a bunch of golden pheasant tippets,

shiny side down. They should be about the length

that, if they were pushed down, they would reach

the bend. On either side of the pheasant tippets,

tie a thin strip of mottled turkey wing a little

longer than the pheasant tippet about the length

that, if pushed down, they would almost reach the

end of the legs.

5. Cut a suitable bunch of deer hair typically the

diameter of a pencil and remove all underfur with

your fingers, a comb, or a dubbing needle. Stack

the deer hair but, before wrapping, be sure to set

the length of the deer hair collar at about half

the length of the golden pheasant tippets. Once

the length is set, wrap in your first deer-hair

bundle. Make three or four wraps, and pull the

thread tight as you let the hair spin around the

shank. Now wrap the thread forward to the front

of the bundle. Push the hair bundle back on the

hook shank against the chenille as tight as you

can in preparation for the next hair bundle.

5. Cut a suitable bunch of deer hair typically the

diameter of a pencil and remove all underfur with

your fingers, a comb, or a dubbing needle. Stack

the deer hair but, before wrapping, be sure to set

the length of the deer hair collar at about half

the length of the golden pheasant tippets. Once

the length is set, wrap in your first deer-hair

bundle. Make three or four wraps, and pull the

thread tight as you let the hair spin around the

shank. Now wrap the thread forward to the front

of the bundle. Push the hair bundle back on the

hook shank against the chenille as tight as you

can in preparation for the next hair bundle.

6. Tie in two or even three more deer-hair bundles,

once again the diameter of a pencil, but this time

have the tips facing forward, towards the hook eye.

Later, this will make the trimming much easier. The

number of hair bundles you can tie in is determined

by the size of the hook. Once you have your hair

attached, bring the thread forward and tie off.

Varnish the thread and base of front hairs and

let dry thoroughly before trimming.

6. Tie in two or even three more deer-hair bundles,

once again the diameter of a pencil, but this time

have the tips facing forward, towards the hook eye.

Later, this will make the trimming much easier. The

number of hair bundles you can tie in is determined

by the size of the hook. Once you have your hair

attached, bring the thread forward and tie off.

Varnish the thread and base of front hairs and

let dry thoroughly before trimming.

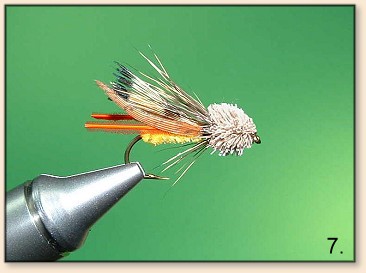

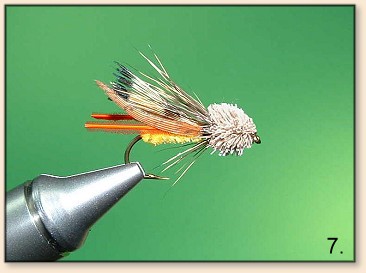

7. Leaving a three hundred-sixty-degree collar,

carefully trim the hair to form the bulbous head.

~ Alan and Richard

7. Leaving a three hundred-sixty-degree collar,

carefully trim the hair to form the bulbous head.

~ Alan and Richard

Special Thanks to:

Gary Soucie for assistance with the provenance of

the Missoulian Spook and the Letort Hopper.

Hans Weilenmann for permission to use the photograph

of the Letort Hopper.

|