It took until 1975 before the Matuka style fly became

popular in the USA and the rest of the world. A 'Streamer'

(historically, belonging to the American East Coast),

is basically a fly with saddle hackle feathers tied

in at the head only. A 'Matuka' is in theory, the same

fly with feathers stripped in a particular way but bound

to the shank, usually with wire. The binding of the feather

to the shank reduces the built-in motion of the fly,

so when fishing a 'Matuka,' you will not have the same

liveliness of a streamer unless you impart more action to

the fly. Nevertheless, the 'Matuka' style flies have

their own unique qualities, the fish seem to like

them, that's for sure.

Some suggest it was one of the many Maori anglers

who first tied the first 'Matuka.' Necessity is the

mother of invention and it may be that the person

who made the first 'Matuka' style fly, may have

done so for a purpose. That purpose being to

eliminate the problem of the long hackle wing

twisting around the gape of a hook while casting.

Mr. Alfred Henry Chaytor was born on a sheep station

in New Zealand's South Island. At the age of fifteen

he set sail for schooling England. In 1910 he

published the angling classic, Letters to a Salmon

Fishers Sons published by Methuen of London. He

was working as a solicitor when the First World War broke

out. Invalided by war service in 1916, fighting in France,

he returned home to New Zealand for convalesce. His

health soon improved and a dose of outdoor air and

North Island sunshine was prescribed. Obeying Doctors

orders, he fished around Lake Tarpo and Rotorua as his

health improved.

Some fourteen years later in 1930 he wrote, Essays

Sporting and Serious, published by Methuen of

London. In this Chaytor mentions the early 'Matuka'

he had seen at Lake Tarpo. I quote:

'a thin red body with a long over wing of mottled

buff-brown bittern's feather, called the Matuka,

the Maori name for the bittern. These flies were

dressed by a good fisherman, who had the luncheon

room at Hamurana...The body is thin, and either red

or light blue, and is dressed on a hook about an inch

long; the wing is very narrow, and about an inch and

a half long and there is no hackle, merely body and

wing. The long thin mottled buff wing of bittern's

feather is supposed to represent one of the small

'inanga', a local fish something resembling tiny

loaches but swimming about in a jerky way, and great

numbers of them could be seen in the shallows around

the lake.'

The Matuka

Australasian Bittern - Botaurus poiciloptilus

Bittern feathers have irregular barred markings, which

when wet, give a fly a similar appearance to one of the

small fish. The 'Matuka' manner of dressing also gives

the fly a very fishy appearance, the top of the wing

characterising a dorsal fin. The actual feather fibres

are soft and mobile, giving the fly a natural living

look. The bird's plumage is so thickly packed that

from one skin, several hundred flies could be produced.

The original 'Matuka' was in general use back before

the First World War and even then the Australasian Bittern

Botaurus poiciloptilus was strictly protected.

Gradually as attitudes to wild life changed, a great number

of 'Matuka' variations began to develop, the 'Parsons Glory'

(Phil Parsons 1930) being one of the most famous. Parsons

used rooster feathers with irregular barred markings.

The fly met the approval of trout and today, the use

of rooster feathers is still a feature in many New

Zealand 'Matuka' designs.

In the early part of the last century, Australian fly

anglers used many 'Old English' fly patterns. Many of

these patterns called for feathers that were not

available in Australia. Imported feathers were expensive,

so to save money, every single imported feather was used

and often the bigger hackles were clipped back. More

locally obtainable feathers were often substituted and

also, various feathers were dyed.

It is unknown how or exactly when in the 1920's the

'Matuka' made its way to Australia. These were tough

times, many families kept chickens in a 'chook-house'

in the back yard for a constant supply of eggs. Feathers

from 'chooks' were ideal for making 'Matuka' style flies.

Fishing and hunting were more that just sport, they were

a way to help feed the family.

Almost always in nature, the male of the species is much

more beautiful, alluring and showy, but rooster feathers

are stiff, impairing less action to the fly than the more

drab looking hen feathers. The use of hen feathers for

wings, instead of cock, seems to be an Australian feature.

Whether or not this was done purposely, so as to give the

fly a more lifelike action is unknown. It may have been a

happy accident; hen feathers from the 'chook house' would

have been very convenient. As this style of fly, using hen

feathers became common, so too did the Sunday roast chicken

dinner for local fly dressers?

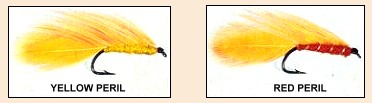

The best of the Australian 'Matuka' flies would be, the

Red and Black (unknown) the 'Green Matuka' (Dick Wigram)

and the two 'Parker's Perils,' the 'Red' and the 'Yellow

Perils' (Critchley Parker).

Critchley Parker was a founder of Melbourne's Herald and

Sun newspapers. In 1937, in the publication, 'Tasmania - The

Jewel of the Commonwealth', he writes:

'I believe that a great proportion of the flies

generally in use can be made from the dyed feathers

of the cock bird known as the white leghorn. I will

admit at once, though, that you must to be properly

equipped have feathers from the peacock and the

golden pheasant. The hawk, the shag and the crow

are very useful. The deep orange, the vivid scarlet

and the purples are necessary for the Purple Emperor,

and the combination of yellow and scarlet from which

I make Parker's Yellow Peril... I invented the

combination and mixed the dyes for this now popular

fly and Mr "Wattie" Williams and Mr Gerald Beauchamp

had the first two I made. They were mainly responsible

for the Yellow Peril's popularity. That was eight years

ago. I have several letters which I treasure, from

professional fly tiers, asking for information as

to the pattern and colours.'

In Dick Wigrams 1938 book, Trout and Fly in Tasmania

published by Sydney, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, Dick states,

and I quote:

'Another very successful fly, in use all over the Great

Lake, is a red and yellow matuka known as the Yellow

Peril. Its originator, Mr Critchley Parker, of Melbourne,

who has fished at the lake for forty years or more,

was kind enough to make known this lure to the

angling public.'

It is unknown just how the feathers were dyed. In the

very early days much before 'Parker's Yellow Peril'

of feather dying, kitchen products were often used,

turmeric as a yellow dye and cochineal for red.

In M.E.Mc Causland's book, Fly Fishing in Australia

and New Zealand, 1947, published by The Specialty

Press Limited, there is a reference to dying of feathers.

I quote:

"Dissolve the amount of dye required in boiling water

and immerse the feathers. Keep the water simmering,

but not boiling and after the feathers have been in

for a few minutes add a desert-spoon of vinegar. Keep

the feathers immersed until the required colour is

obtained and then remove them and place in a paper

bag; screw up the mouth of the bag and place near a

fire or gas stove. They will quickly dry in this way,

but if allowed to dry slowly will loose a little of

their lustre."

Yellow Peril (Critchley Parker)

Hook: Size # 6 -10 down eye, wet fly hook.

Thread: Black.

Rib: Oval gold tinsel.

Body: Yellow wool or suitable substitute.

Wing: Two scarlet and two yellow dyed hen

feathers stripped to fit shank matuka style, concave

side facing inwards. The two scarlet feathers are

together on the inside.

Head: Black and well formed.

Comment: The Red Peril is exactly the same

but it has a body made from red wool or suitable

substitute. The choice of two patterns gave the

angler a choice of pattern for different conditions.

Method:

1. Start fly as normal and wrap thread to rear of

hook tying in some oval gold tinsel to rib the wing later.

2. Dub wool or suitable substitute material forming

the body leaving plenty of room at the head of the

hook to tie in the wing and finish off the fly.

3. Find 4 matching hackle dyed feathers, two of each.

Length is subject to personal taste but about two times

the length of the hook shank should be right. Tie in

these feathers at the head of the fly.

4. Now use the wire rib to secure the rest of the wing

to the top of the body. This is the most important step

in making the fly. The wing must be flat along the shank

and vertical. Use your fingers to separate and spike the

feather fibres to make a small window to wrap the rib

through and try to keep the rib vertical over the body,

spiral the rub forward under the body not over the wing.

Make as four or five wraps to secure the wing and then

tie off the rib. ~ Alan Shepherd

|