|

I often wondered what the people who were recipients of

my father's crafts thought to themselves. How they felt,

what they perceived, where their thoughts found a quiet

corner to contemplate.

My father was a boat builder, jewelry maker, woodworker

and woodcarver, among many things. From a battered old shop

with a dirt floor in the backyard, magic flowed in a ceaseless

stream, most to be sold in the craft shop my grandparents

ran out of a room of this old house I live in now. I would

sit with him in that old shop, watch the boat or the watchband

or bolo tie come together, see it leave, but I could not

comprehend what the customer who might wander into the crafts

shop at my grandparents' might feel, think, see there.

Even in my later years when, sadly, after my father's death

I found the drive to build on my own was overwhelming, I

could not imagine what really lurked behind the praise for

a curly maple armoire, a bookshelf, a dresser of drawers.

Perhaps I am beginning to understand it, as I grow older, as

I perceive from my own quite corner at the side-edge of a life.

It was nearly a year ago that arrangements were made with

Harry Boyd for a rod. Harry is a bamboo rodmaker who hails

from Louisiana, so a Boyd Rod Co. model would be a natural

for me. I had only met Harry once, briefly, at a club conclave

in Lafayette, but we had corresponded by email many times.

I was thinking of a bass rod, something at eight feet, and

Harry suggested a seven weight based on the Dickerson Guide

Special taper, hollow built. He even suggested it would be

suitable for marsh redfish and speckled trout. Sounded like

a winner to me and so I agreed.

As most of you kind folks know, it was quite a busy year

for me: Two television programs on Fly Fishing America,

two hurricanes and all that. The time passed quickly with

all the excitement down here, and before I knew it, Harry

was telling me the rod was ready. He would have been happy

to mail it to me, but I insisted on driving to Winnsboro,

Louisiana to pick it up. On the one hand I couldn't bear

the thought of entrusting it to the mail, though rodmakers

do so all the time, but also, I felt like it was the right

thing to do, since Harry and I had only briefly had time

to talk face-to-face.

I had only been exposed to a few cane rods, but loved them

greatly. Of the bunch my favorite was a nine-foot Granger

Victory, pre-Wright and McGill takeover vintage. A

medium-action rod, the Victory was nonetheless my "go to"

rod for bass fishing around here.

The first trip was a bust due to bad weather, but the following

weekend a buddy of mine and I took to the road for the four-hour

trip to Winnsboro. Upon arriving, I had written down Harry's

directions to his house: Turn here. Then turn there. One driveway,

I counted aloud, second driveway...

"Maybe it's the one with that guy casting a fly rod in the

driveway," my pal said. Sure enough, there was Harry, and

there was an awful lot of line out in front on him as I

turned in. Quick introductions and Harry said, "This isn't

your rod. I decided to build one for myself, too," and then

ushered us inside where we met Harry's wife and, without a

lot of fanfare but a broad grin, Harry put a tube in my hand.

"Here's your rod," he said.

I used to wonder what people felt and thought and perceived

when they took delivery of one of my father's wooden bateaus

or calumets; one of my grandparents river cane baskets or one

of my piddlings in the woodshop. I used to guess at the emotions,

thoughts. Now I think I know.

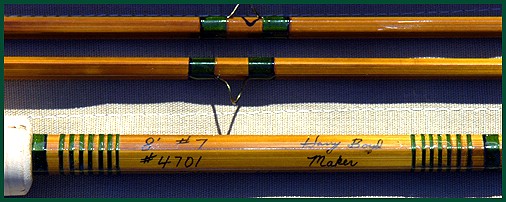

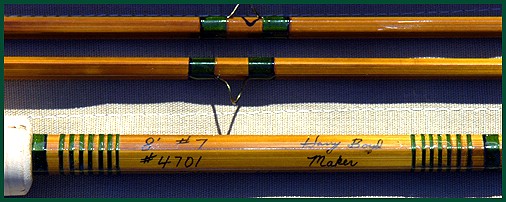

As the top came off and the rod bag came out the tube, then the

butt and two tips of the rod emerged, I knew what it was like.

The burl reel seat insert, the fine, bright reel seat, green

wraps, black tipping, and oh, the cane. Glowing, it was, speaking,

too. He had inscribed "Native Waters" on one flat and I felt

myself flush with pride.

What I have long loved about antique firearms, handmade furniture,

bamboo rods, many such things was the mark of the craftsman. Men

like my father, like my grandfather, but they were always detached.

Distant. I didn't know the name or the face behind the Granger,

the old Damascus twist double-barrel that had been in the family

for generations, the Edison Amberola in the den. Certainly I knew

my father and grandfather and grandmother, but the detachment

was still there, somehow. From the inside, looking out I still

couldn't perceive the entirety of it.

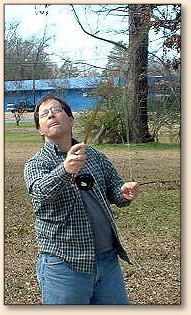

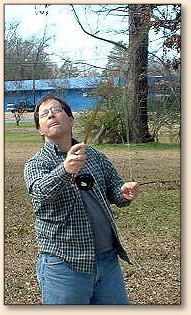

But as Harry led us back outside and I strung up the rod and before

I knew it, threw an awful lot of line out - more than I had ever

cast before with any rod - I saw from the corner of my eye Harry

beaming like a proud parent. Like the way my father would grin

widely when a boat left on a shiny galvanized trailer, or a violin

cradled in the crook of an arm, or a turquoise and silver band on

a wrist. I understood at last that the beauty of the craft is only

half the story: The other half is that it moved directly from the

maker's hand to the user's, the wearer's.

But as Harry led us back outside and I strung up the rod and before

I knew it, threw an awful lot of line out - more than I had ever

cast before with any rod - I saw from the corner of my eye Harry

beaming like a proud parent. Like the way my father would grin

widely when a boat left on a shiny galvanized trailer, or a violin

cradled in the crook of an arm, or a turquoise and silver band on

a wrist. I understood at last that the beauty of the craft is only

half the story: The other half is that it moved directly from the

maker's hand to the user's, the wearer's.

I think I said something like, "It's exquisite," but Harry will

have to tell you for sure, because I was in awe of the perfectly

balanced and extraordinarily powerful rod in my hand, conjuring

line behind and in front of me. I've never felt such wonder in

a fly rod, and sometimes when I'm casting it in the yard these

days, waiting for spring to actually get it out on the water,

I wonder if I ever will again.

"You weren't even using a haul," Harry observed, and I timidly

admitted I am terrible at the fabled double-haul, but with that

rod, I hardly needed it, even into the wind as I was casting.

We spent a couple hours with Harry in his rod making shop, a

tour which was nothing short of fascinating and added so much

more depth and perception to the rod in the tube that would be

going home with me. As the son and grandson of craftsmen, I

found myself within shops past and present, and the vision

of the craftsman huddled over his work, satisfied only with

the very best he could muster, unwilling to put his name on

anything else, ran as true in my memories as it did that day

standing there with Harry Boyd.

Then it was time to be off. Harry had a speaking engagement

and we had that four-hour ride back. We shook hands and Harry

said he wanted pictures of me and the first fish caught with

the rod. He said if I had any problems whatsoever with it

he'd take care of it. I thanked him again and pointed the

hood of the truck towards home.

I still haven't gotten it wet. The weather's just not

cooperating here, the water is high and muddy even when

temperatures are passable. But spring's just around the

corner, and Harry will get his picture. I take it out in

the yard often, and grow more enamored of it each time.

That's what it's all about, holding the work of a true

craftsman, who put it from his or her hand to yours, no

matter if it's a fly rod or something else. True craftsmen

let a little part of themselves go out with each piece.

The picture's coming Harry. It's going to be a great spring!

Boyd Rod Company can be reached at www.canerods.com.

~ Roger

|

But as Harry led us back outside and I strung up the rod and before

I knew it, threw an awful lot of line out - more than I had ever

cast before with any rod - I saw from the corner of my eye Harry

beaming like a proud parent. Like the way my father would grin

widely when a boat left on a shiny galvanized trailer, or a violin

cradled in the crook of an arm, or a turquoise and silver band on

a wrist. I understood at last that the beauty of the craft is only

half the story: The other half is that it moved directly from the

maker's hand to the user's, the wearer's.

But as Harry led us back outside and I strung up the rod and before

I knew it, threw an awful lot of line out - more than I had ever

cast before with any rod - I saw from the corner of my eye Harry

beaming like a proud parent. Like the way my father would grin

widely when a boat left on a shiny galvanized trailer, or a violin

cradled in the crook of an arm, or a turquoise and silver band on

a wrist. I understood at last that the beauty of the craft is only

half the story: The other half is that it moved directly from the

maker's hand to the user's, the wearer's.