Part Fourty-two |

Mark Sosin's Guide To Releasing Fish

By Mark Sosin

Part Fourty-two |

By Mark Sosin

|

We thank Mark Sossin for permission to share this information with our readers. For more good information check out his website at https://www.saltwaterjournal.com.

The jury reached its verdict a long time ago. Repeated tagging studies

on a multitude of species from shark to striped bass and redfish to

billfish demonstrate convincingly that the majority of fish can

survive being caught if they are released correctly. Scientists

confirm these findings. Jim Whittington, a state biologist in

Florida who focuses his attention on the coveted snook, reports that

there is only about a 3 percent mortality in a catch-and-release

fishery for this species during the off season. A bleeding fish

prompts the misconception that it will die anyway, so we might

as well toss it in the fishbox. These animals don't suffer from

hemophilia and don't bleed to death as readily as one would suspect. It's worth

the effort to revive and release a bleeding fish. Tagging results show that

many will survive.

The jury reached its verdict a long time ago. Repeated tagging studies

on a multitude of species from shark to striped bass and redfish to

billfish demonstrate convincingly that the majority of fish can

survive being caught if they are released correctly. Scientists

confirm these findings. Jim Whittington, a state biologist in

Florida who focuses his attention on the coveted snook, reports that

there is only about a 3 percent mortality in a catch-and-release

fishery for this species during the off season. A bleeding fish

prompts the misconception that it will die anyway, so we might

as well toss it in the fishbox. These animals don't suffer from

hemophilia and don't bleed to death as readily as one would suspect. It's worth

the effort to revive and release a bleeding fish. Tagging results show that

many will survive.

WHY RELEASE FISH

Size, season, and bag regulations make the release of many fish species

mandatory. Since you don't have an option, it's important that you become a

fishery manager and make sure the fish survives. Even where regulations

don't exist, a personal commitment to conservation through catch-and-release

adds an extra measure of fun to a day on the water. Stressed fish populations

(and that includes most of the popular recreational species) need your help to

recover.

THE FIRST STEPS

If you intend to release a fish, try to set the hook immediately so that your

quarry does not swallow the bait or lure. Virtually any gamester can grab and

swallow a bait in less than a single second. The idea that they must swim off

with it, turn it around, mash it, or perform countless other operations is more

speculation than reality. Sure there are times a fish will "mouth" a bait, but

most swallow their prey instantly and try to grab another.

Once the fish is hooked, try to land it quickly. If you insist on playing your

quarry to exhaustion, chances for survival diminish. If you are dragging a fish

out of deep water, however, slow down so that the fish can adjust to the

change in pressure and its swim bladder won't expand dramatically.

On lures with multiple treble hooks, it helps to remove one set of trebles or cut

one hook off each set of trebles. I crush the barbs on my hooks (including

trebles) primarily for easier penetration (one hooks more fish), but also to

facilitate removing the hook.

SO YOU WANT YOUR FISH MOUNTED Beginners often fall victim to captains who insist they must bring the dead fish back if the customer wants to have it mounted. The persuasive talk tries to convince you that you must kill the fish so that you will get YOUR fish back from the taxidermist. Today, almost all wall mounts are made from fiberglass molds and every part can be created to look as real as it did when the fish was alongside the boat. Don't let anyone tell you they need the bill and sail of a sailfish or the teeth of a barracuda. You can telephone any major taxidermist right now and order a fish mount of most popular species in whatever size you specify. They already have the molds. Even if you release a fish and later decide you want to hang a mount on the wall, make the phone call. That's all it really takes. The only exception is a rare and unusual species where they might want the whole fish to create the mold.

The first rule of release suggests you leave the fish in the water with its body

just under the surface and don't handle it at all. Use a tool to remove the hook

or, if the fish is hooked deeply, cut the leader as close to the mouth as

practical. That creates the least amount of stress. A small gaff hook or a

curved-end release tool enables you to engage the bend in the fishhook and

pull it out against the barb while maintaining pressure on the leader. Once you

learn this method, it's quick and easy.

|

|

Whether the fish is alongside the boat or in the surf, you want to keep it from

thrashing and injuring itself. If necessary, use a net to land your quarry,

remembering that the strands of the net help to remove the mucous body

coating which protects the fish against infection. On larger animals, a short,

release gaff slipped through the lower jaw helps to hold your quarry while you

remove the hook. A tool called The Lipper holds the jaws of smaller fish

without applying excessive pressure. Keep in mind that a tailer is another tool

that enables you to handle a fish without injuring it. The tailer is slipped over

the tail of the fish and pulled tight. You can then lift the fish out of the water

backward and it usually does not struggle too much.

If you must handle a fish, use a wet glove or a towel to obtain a positive grip

on the body. Sticking your fingers in the eyes of a fish or into the gills will

seriously injure your quarry. You may certainly cover the eyes of the fish with

a wet towel and turn it upside down. These moves tend to have a calming

effect. Above all, get the fish back in the water as soon as possible.

BE CAREFUL

Sharp teeth are not the only danger in

handling a fish. Many species have

spines on their fins or protruding from

their bodies that can make nasty

puncture wounds. Razor edges often

trace along the gill plates and these can

cut a hand easily. The key lies in

knowing where to hold each species and

to grip the fish firmly and securely

without crushing it to death.

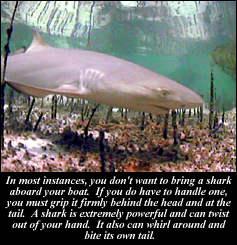

Sharks are one species you don't want to

bring in the boat. If you can't remove the

hook easily with a tool while the fish is in

the water, cut the leader and let it swim off. Sharks have a cartilaginous

skeleton instead of a bony one. This means they can just about bite their own

tail. If you hold a shark improperly, the jaws will find your hand.

Other species such as dolphin or cobia will thrash around in a boat and may

possibly injure themselves (or you) as well as destroy valuable equipment. If

possible, deal with them in the water or use a tailer and a glove for more

control.

REMOVE THE HOOK

No matter what material they are made from, hooks do not rust out in a couple

of days. Rust requires oxygen and there isn't a lot of oxygen floating around

underwater. It is true, however, that fish are often able to work a hook loose

and, in many instances, they can feed normally with a hook in their mouth.

Having said that, it is important to remove the hook if you can do so without

damaging vital organs of the fish. There are special tools that help remove

hooks when they are imbedded deep in the throat. Needle-nose pliers,

hemostats, hookouts and other devices often allow you to reach deeper in the

mouth. It's a judgement call. If you are going to hurt the fish, leave the hook

where it is and cut the leader as close to the jaw as possible.

Avoid jerking or popping the leader to break it with the hook in the fish. The

hook tends to tear and often damages vital organs causing the fish to

eventually die. Anglers fishing release tournaments for billfish sometimes

resort to this practice. It can kill the fish even though the angler intended to

release his catch.

GUESS THE WEIGHT

If you want to estimate the weight of a fish before releasing it,

there is a simple formula. All you need to do is measure the

length and the girth of the fish. Square the girth, multiply it by the

length and divide by 800 for the basic cylindrical fish shape. For a

long, thin fish such as a barracuda, divide by 900 instead of 800.

A soft, sewing tape measure works best, but you have some

options. The easiest is to measure with a piece of monofilament

and then worry about the length of the mono after the fish has

been released. You can make a tool to give you the length by

attaching some parachute cord to a snap swivel. Mark the cord

every 12 inches. When the fish is alongside the boat, snap the

cord around your leader and let it stream back to the nose of the

fish. You can then eyeball the length. The same cord can be

wrapped around the fish quickly to give you the girth.

DEALING WITH BILLFISH

Sailfish and marlin rank as the offshore glamour species and most anglers

choose to release them. Stocks of blue and white marlin in the Atlantic, for

example, are at less than 25 percent of maximum sustainable yield. They're in

serious trouble.

Follow the same procedures as you would with any other species. Try to

control the fish at boatside and remove the hook if at all possible. With sailfish,

white marlin, and smaller blue marlin, one can grab the bill and hold the head

of the fish underwater (it remains calmer) while the hook is being removed. If

you do grab the bill, make sure your thumbs face each other. That keeps the

fish from jumping toward you, because your hands and arms will lead the fish

clear automatically. There is a relatively new tool that can be slipped over the

bill of a sailfish and marlin, enabling you to control the fish and hold the head

underwater while the hook is removed and the fish is being tagged. This tool

should be on the market about the time you read this.

If you are going to place a tag in a sail or marlin, try to get the fish alongside

the boat first. Attempting to stab a fish with a long tag stick while it is airborne

defeats the purpose. The tag must be planted in the shoulder of the fish well

back from the head and gills. Those anglers and mates who jab at the fish

often miss the target area and wind up puncturing the body cavity which

causes the death of the billfish.

TURNING THE FISH LOOSE

This is the critical moment. You don't want your quarry to turn belly up, sink,

or ease off without enough strength to avoid a larger predator. The easiest

method is to simply place the fish in the water facing into the current or any

flow of water while you support its belly and hold the tail gently. If the fish

needs resuscitation, work it back and forth gently, forcing water through its

gills. You will sense when the fish regains strength. At that point, it will

actually swim out of your hands.

With a billfish, hold your quarry by the bill and force the head underwater.

Have someone kick the boat in gear and move forward very slowly. This

pushes oxygen through the gills and the fish will eventually be ready to swim

off.

If you release a fish and it turns over or doesn't swim off, try to get the fish

again and resuscitate it until it is able to swim on its own. A fish taken from

deep water usually has an expanded air bladder and cannot return to depth

until the air is pushed out. The easiest way to handle this is with an ice pick or

hook point. Puncture the air bladder, squeeze the air out, and release the fish.

It should go down.

Although scientists recommend a gentle release without tossing the fish back

unceremoniously, there are times when a more forceful water entry makes a

difference. Sometimes with tunas and bonitos its best to push the fish into the

water head first, driving it as deep as you can. The same approach works with

other species that come up from deeper water such as amberjack.

If you handle a fish with care and release it correctly, your quarry stands an

excellent chance of survival. To me, there's no greater sight on the water than

to watch a proud gamefish swim off slowly with nothing hurt more than its

pride. Try it; releasing fish becomes habit forming and makes you feel good in

the process.~ Mark Sossin |

| Previous Eye of the Guide Articles |