Callibaetis Mayfly Nymph - Smith's All Natural

By Brian Smith

The early spring hatches of Callibaetis is

one of the year's most important to stillwater

fly fishers. The keys to successful outings

when this prolific species is hatching are

learning to anticipate and recognize the

signals of mayfly activity, and having a

suitable nymph pattern.

An emerging adult dun is recognized by its

sudden appearance on the water, joyfully

sailing along on the surface breeze for a

short distance, then flying off into shoreline

vegetation and tree cover from which they emerge

to mate. When mating is over, clouds of female

spinners engage in a flitting, bouncing dance

over the water's surface as they return to

deposit their eggs. When they've finished,

they drop to the water and die, their wings

spread out in spent configuration.

When trout are feeding on duns or spinners

on the surface, they provide wonderful dry

fly fishing. However, trout feed much more

prolifically on the nymphs as they rise

through the water column above the shoal,

often popping into adulthood while several

feet underwater. Consequently, fishing nymphs

during the emergence presents a much greater

opportunity for lots of action. One of the

first signs that there is a major migration

of nymphs to the surface is the appearance

of the first few duns.

In stillwaters, hatches of Callibaetis,

which can be heart stopping, take place in

the shallows, usually in less than six feet

of water. Therefore, these nymphs are best

fished with a floating line. Whether you're

fishing from a floating platform or from the

shore, it's best to cast into deeper water,

then retrieve toward shallower water, using

hand-twists of the fly line, interspersed by

quick jerks and 10-second pauses, as you lift

the fly from deep to shallow water. Strong

stillwater hatches of any migrating insect

are best fished this way.

Although Callibaetis nymphs are

abundant in many colors and sizes, four colors

are generally sufficient to handle all

situations olive gray, rusty brown, dark gray

and pale gray. Primary feathers dyed olive

gray and pale gray, natural goose and rust-colored

pheasant swordtail are excellent natural imitators

of a nymph's prominent gills. They are also

effective for constructing the thorax. Rusty

brown and dark gray nymphs work best in brown,

tannin stained waters, while pale gray and olive

gray are the most effective in clear waters,

rich with aquatic life.

Mature Callibaetis nymphs possess

two important features that cannot be overlooked

in representation a prominent three-pronged tail,

and a darkening of the thorax area. The tail is

tied one-half the body length with stiff feather

hackle or primary biots in the same color used

for the body.

When the nymph approaches maturity, the wing case

area darkens. This is best represented by a dark,

natural fiber, such as peacock herl, which also

adds texture and a light reflecting property to

the fly.

Dressing flies with natural materials adds another

critical ingredient that creates an overall

impression of a living insect tiny air bubbles.

Natural materials trap and hold these bubbles

more effectively than synthetic materials.

Natural Callibaetis Nymph Recipe:

Hook: Tiemco 200R, sizes #12 - #16.

Thread: Brown UTC.

Tail: 3 pheasant tail fibers.

Body: 3-4 pheasant tail fibers.

Wingcase: 3 strands of peacock herl.

Thorax: 4-5 pheasant tail fibers.

Legs: Grouse hackle, brown gray phase.

Tying Steps

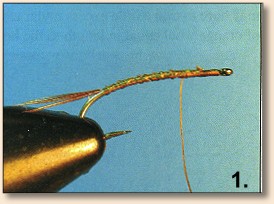

Step 1: Start tying the thread just

behind the hook eye. Choose a rusty

brown phase of pheasant sword for the

entire nymph pattern. Tie in the tail

so that it extends one half of the

body length past the bend.

Step 2: Bind body fibers in at the bend,

wind them toward the eye of the hook for

2/3 of the shank length, and tie off.

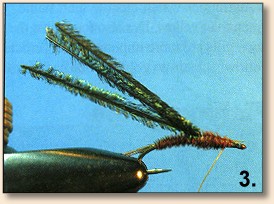

Step 3: Tie in the peacock herls for the

wing case at the point where you've tied

off the body, followed by the thorax material.

Wrap the thorax material up the shank to

just behind the eye.

Step 4: Choose a brown phase grouse hackle,

spread the fibers, clip the tip from the

hackle, leaving 6-8 fibers on each side

of the feather. Tie the whole feather on

just behind the eye and over the thorax,

then spread the fibers to each side of

the fly.

Step 5: Fold the wingcase over the thorax

and hackle, and bind it down and finish

the head. A final touch is to draw the

tail fibers gently between your thumbnail

and fingertip, which causes them to curve upward.

~ Brian Smith

Credits: This article is from the

Canadian Fly Fisher magazine. We appreciate use permission!

Our Man In Canada Archives

|