Great Lakes Spring Steelhead

Tactics for Small Streams

By Chris Marshall

I shall never forget my first Great Lakes steelhead.

I was fishing the Wolf River near Nipigon in the fall

of 1968 after moving to Fort William (now Thunder Bay)

that summer. Although I cannot now remember whether

the month was October or November, the years have

not dimmed the image of that fish as it came to my

hand in the late afternoon-burning bright silver

among granite boulders in the dark water under a

grey sky.

I remained at the north end of Lake Superior for

just three years. I fished often-anywhere and for

anything, but it was the steelhead which fascinated

me most. Although I fished for them at every

opportunity, they remained elusive. My success was

sporadic, despite the local knowledge and mentoring

of my usual fishing partner, Tom Mikulinsky, a Grade

12 student at Sir Winston Churchill Secondary School

where I taught. While we caught fish, all too

frequently we seemed to miss the main run, arriving

at the water either too early or too late. Perhaps

the problem was me, for often when Tom went without

me, he managed to get the timing right.

Consequently, although I welcomed the kinder climate

and superb warm water fishing when I returned to the

Quinte region in 1971, the elusive, enigmatic

steelhead far to the northwest continued to haunt

me.

Then, I discovered the steelhead of Lake Ontario.

Again, it was one of my students who opened the

door, when he took me to Lakeport one April in

the mid-seventies. Since then, I've pursued the

dream in the smaller, gentler streams of central

Lake Ontario, and although these lack the enthralling

wildness of their counterparts in the north, they

suffice.

Fall or Spring?

The Lake Ontario tributaries east of Toronto are

small, and although steelhead start gathering at

the mouths of these in the fall, few penetrate far

upstream until the spring. This is unfortunate, as

steelhead are brighter, firmer and more energetic

in the fall than they are in the spring. However,

as rain and snowmelt begin to swell the flow in

March, the streams fill with fish, and the fly

fishing opportunities are overwhelmingly greater.

These fish have hung around the mouths of the

tributaries throughout the winter, making occasional

forays a short way upstream when the occasional mild

spell increased the flow, but dropping back to the

lake as the flow diminished with the return of

sub-zero temperatures. In milder years, there will

be enough fish in the lower reaches to provide good

fishing as early as February, but usually this does

not happen until March. The run, however, tends to

peak in the first part of April. In normal years,

most steelhead will have spawned by the end of April,

although there are always a number which procrastinate

until early May.

Once they've spawned, some fish will start dropping

back to the lake within days, while others will hang

around, holding in the deeper pools until as late as

June. Rain is the major factor in determining the

timing of this return migration: the more rain,

the higher the flow and earlier the return.

Tactics: Stream

On mild days in winter, it's possible to target the

fish hanging around the stream mouths, provided there's

no onshore wind pushing the ice pack against the shore

and clouding the water with silt. In such conditions,

steelhead tend to stay offshore where the water is

clear.

On mild days in winter, it's possible to target the

fish hanging around the stream mouths, provided there's

no onshore wind pushing the ice pack against the shore

and clouding the water with silt. In such conditions,

steelhead tend to stay offshore where the water is

clear.

Stream mouths vary. Some are deep, slow-moving channels,

little more than inland extensions of the lake, which

offer excellent opportunities for bait and hardware

fishers, but little for fly fishers. Others, however,

are channels through the shoreline gravel, with

streamy flows thrusting out into the lake. These

are the places to fly fish. The best tactic is to

wade into the lake itself adjacent to the flow and

fish a streamer on a swing across and down, finishing

with an upstream strip, or cast a nymph, Woolly Bugger

or egg imitation upstream and dead drift it back until

it starts to lift downstream. In both cases, the fly

must be fished close to the bottom where the fish

inevitably hold.

Sometimes in mild spells in March, the flow will cut

a channel through the shoreline ice pack, creating

an extension of the stream out into the lake.

Encountering this is serendipity, as it can be

fished as if it were a regular stream running

between terrestrial banks. Fish will frequently

hold along the undercut ice edges.

Tactics: The Streams Themselves

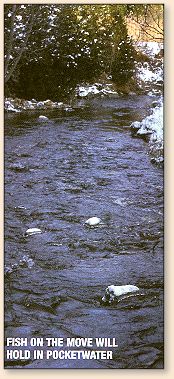

Once steelhead have entered the stream in earnest,

in late March and early April, they'll stay in the

stream even in dry conditions when the water is clear

and the levels relatively low. This is the best time

to target them, rather than when the water is running

high and stained. Many will be holding in the pools and

deeper runs, but don't neglect pocket water, for a

number will also hold there, even in tiny pockets

which most anglers overlook.

While the pools and deeper runs can be fished blind,

either with a swung streamer or a with a dead-drifted

nymph or egg pattern, the best tactic is to sight fish.

Pocket water in riffles is ideal for this. Moreover,

the bait fishers, who crowd the popular pools, rarely

bother with these places.

Once fish or likely lies have been located, get as

close as you can downstream or across, cast the fly

upstream, and drift it down. If you can see the fish,

drift the fly as close to the fish's nose as possible

and watch for the white glint of an opening mouth

before setting the hook. If you can't see the fish,

set the hook at any check or unnatural movement of

the drifting leader-however, insignificant. Make sure

you use enough weight on the leader or the fly to

ensure the fly trundles along close to the bottom.

Always fish as short a line as possible and leave

as short a portion of the line as possible on the

water, for this enables optimum line control and

detection of takes. This means that there's rarely

any need for a strike indicator if you're using a

short leader, as the short length of line on the

water serves this purpose. Moreover, much of the

time, you should be able to see the fish you're

targeting and watch it take. This is a far more

effective method of detecting a take than watching

a strike indicator or the line. While you should

make your approach to fish or likely lies as sneakily

as possible, you'll find that steelhead are much

less easily spooked than resident trout, and that

its possible to get quite close to them. Moreover,

because the banks of these small streams are often

heavily bushed, making conventional casting difficult,

a close approach enables short flip casts and roll

casts, eliminating the need for a back cast and the

inevitable hang-ups in streamside branches.

Locating Fish

Migrating steelhead usually hold in or close to cover.

Turbulent pockets and deep holes in pools can provide

this, but outside these places, they will tend to lurk

by deadfalls, overhanging tree branches, boulders,

tree roots and undercut banks. The best tactic is to

walk stealthily upstream and scrutinise all likely

places. While it doesn't take long to recognise the

lies, the fish are not always easy to spot, and it

takes some time and practice in order to become adept.

Nevertheless, the fly fisher who perseveres will be

rewarded with greater success on the water.

Gear

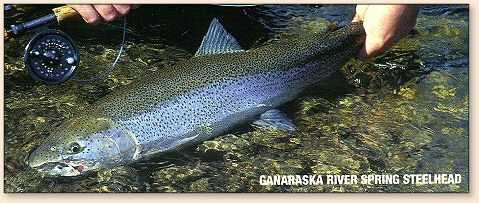

Although these Lake Ontario tributaries are

small, the steelhead which enter them can be

big-as much as twenty pounds or more. At the

same time, because they're small, there's no

need for gear designed for long casts. Therefore,

the rod should have enough backbone to handle

big fish in tight spaces, yet also have the

facility for making short, delicate casts. A

nine foot-weight loaded with a weight-forward

number eight floating line is ideal. The long

rod facilitates line control, and the heavier

line helps in making short casts.

Because handling big fish on these small streams

involves following them on foot, rather than

letting them run and playing them on the reel,

there's usually little need for a big reel with

a sophisticated drag or lots of backing. The leader

should be short, between four and six feet, with

a tippet no lighter than six pounds test. Eight

pound test is better, especially where it's necessary

to play fish tightly to keep them out of snags.

Flies

While there are situations where streamers are

effective, most situations are best fished with

dead-drifted nymphs and egg patterns.

Streamers: Avoid bulky winged patterns

which are hard to get down near the bottom and

keep there. Concentrate instead on sparsely-tied

hair wings on #6 and #8 hooks. Patterns which

suggest smelt and alewives are good at the stream

mouths and the lake shore. Traditional hair wings

with a touch of flash and bright red or chartreuse

work well in the streams themselves.

Flies for Dead-drifting: While most small

stream steelheaders have their own personal

favourites, most buggy, impressionistic nymph

patterns are effective. However, it's hard to

beat the ubiquitous Woolly Bugger (sizes #10 to

#6) in subdued, natural colours, especially black.

Shellbacks (#10 and #8), such as the Spring Wiggler

in fluorescent orange, yellow, and chartreuse also

work well. Single egg patterns tied on short-shank,

wide-gape hooks in fluorescent red, orange, yellow,

chartreuse, or combinations of these are also good,

especially with a few strands of Krystal Flash tied

in at the tail. ~ CM

Credit: Excerpt from the January/March 2004

issue of The Canadian Fly Fisher. We appreciate use

permission.

Our Man In Canada Archives

|