The lie was not a natural structure, but the trout

did not know that. She had moved into the pool

after an unusual summer flood had torn away the

undercut bank where she'd spend the previous three

seasons. Her new lie was better than the old one,

though. Cedar logs lay parallel to the current,

overhanging cleanly washed gravel.

She was resting, secure with the logs to one side and

above her and the thrust of the current to the other side.

She paid no particular attention to the twisted wire tying

the logs together or the steel bar driven into the streambed

to anchor them. They were just part of the landscape.

For Mike Baxter, however, these artifacts had very special

significance.

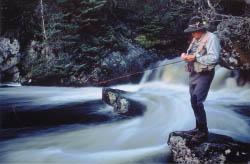

He crouched among the milkweed and goldenrod at the tail

of the pool. The sun was just setting behind the farm

on the hill upstream. He was relaxed, waiting for the

Isonychia hatch - never prolific this late in the summer,

but sufficient to entice the bigger trout to feed on the

surface.

As he filled his pipe, he examined the log cribbing against

the bank upstream to his right. Even though the flow was

at its usual late summer level, the current chuckled bristly

along the edges of the logs. It was a lovely pool - hard

to fish due to the drag produced by the complex, ever-changing

eddies, but it was a challenge and it held big trout.

Earlier in the season, when the stream was much more crowded,

it was a popular place, and Mike always seemed to find some

other angler there when he arrived or, if he had managed to

get there first, he'd been disturbed by somebody clumping

down the bank. He preferred the summer - the fishing was

harder, but the crowds were gone.

The log cribbing in the pool had been built by Mike's

fly-fishing club the previous season to protect the

eroding bank and to provide cover for trout. It had

proved to be one of the more successful of the club's

conservation projects. Since opening weekend, there

had always been fish in the deep, gravelly run against

the logs. This was why it had become so popular.

Now, the dogwoods and grasses planted in the backfill

behind the logs were in full leaf, hiding the raw

construction scars left by the work party more than

nine months earlier. Mike smiled wryly to himself

as he remembered the day they'd pounded in the last

T-bar and twisted the last strand of wire.

* * *

It was painfully cold. Mike stood in water up to his

waist, leaning against the new section of cribbing.

His exposed hands were red and puffy from the near

freezing water, but he kept his grip on the pliers

and gave the stiff wire a final twist to tighten the

log securely against the T-bar. Then, dropping the

pliers on the logs, he raised his hands to his mouth

and tried to blow the ache away with his warm breath.

It didn't help much. His whole body was chilled to

the bone. Even his mind seemed frozen.

I'd better get out and warm up a bit, he decided, rousing himself.

But he hesitated. If he took a rest, the others would,

too, and they'd be slow to get back to work again. He

didn't really blame them. It was a hell of a day to be

working on the stream - and they were all older than he

was. Still, he was the one working in the icy water.

Could he get them back to work quickly enough so they

could finish the job? It was the 29th of November.

They were lucky it wasn't ten below zero. It was too

much to expect the unseasonably warm ten above to last

into December. He know this was the last chance to finish

the job before the following spring . . .spring! It

seemed an age away . . .

"You OK, Mike?"

Winter came back.

"Come on out. We're going to take a break. You must be

half-dead with cold in there. Here, grab my hand."

Jack Milner's gloved hand reach down to him. Mike

grabbed it and pulled himself out of the stream and

on to the logs.

The others had a fire going in the lee of a clump of

big cedars. Thankfully, Mike sat down on a log and

took the mug of hot chocolate Dan Fergusson offered

him. Dan was at least seventy and had a heart condition,

but he always came out to work parties. In fact, all

three of the others were well over fifty. Mike, at

thirty-one, was the baby. He listened condescendingly to their

half-serious grumbling as he warmed himself at the fire.

"Thought we'd have had a few more come out today."

"Too damn cold. Gotta be crazy."

"Snow's coming."

"They're all inside watching the football game on TV."

"Nah, Ross and Al and some of the others are off hunting."

"Can't expect people to come out in weather like this."

"You did!"

Mike was only too aware of the problem. As club

conservation chairman for the past three years

he'd been frustrated by the lame pattern of member

involvement (or lack of it) in work parties. The

spring wasn't too bad, when anticipation of the

opening of the trout season generated initial enthusiasm

for working on the stream. But the enthusiasm quickly

waned once the season opened. He'd almost given up

trying to call work parties in the summer because of

poor turnouts. Oh, the excuses were legitimate enough

for the most part - family obligations, vacations, and

so on. There really weren't all that many freeloaders.

But it always seemed to be the same handful who could

be relied upon to show up when needed. The past year

had been the worse, as he'd lost his two best workers.

Dave Jacklin had moved out west when the factory in

which he was a machinist had closed down, and Ted Delaney

had slipped a disc while jogging.

Despite the drastic reduction of his work force, Mike

had been loathe to abandon the half-completed log cribbing

project, knowing that if it were not securely wired in,

it would most likely be washed away in the spring runoff.

But without Dave and Ted it had almost proved too big a

job. Even now, in late November, they had yet to finish.

"Another cup, Mike?" Dan Fergusson was holding the thermos out at him.

"Thanks, I need it."

Dan filled up his mug.

I'd better get back to work, Mike worried as he sipped

at the hot, sweet chocolate.

A flake of snow drifted from the leaden sky. Then

another, Mike dragged himself up. "Let's finish it,"

he encouraged, mustering the others.

As he eased himself back into the water the snow

intensified. The wind was beginning to freshen, too.

Only six more to wire in, he told himself, as Jack handed

him one end of double strand of wire. The other end had

already been attached to a T-bar driven into the bank.

Dan waited with a short stick to twist the wire tight,

and a hammer and a ten-inch ardox nail to pin it to the

log. Moved on to the next T-bar. By the time they

tightened the last strand of wire, it was snowing hard.

Mike was exhausted. I must be crazy, he thought.

Somebody else can do the job next year.

Dan had built the fire up, and the cedars provided some

shelter from the driving snow. They clustered around

the flames, absorbing as much of its warmth as the could,

indulging in the last of the hot chocolate before they

picked up their tools for the long walk back to the road.

They walked in single file, silently, along the muddy

path through the meadow, totally absorbed in the task

of forcing their feet to make each step. The snow had

eased to a few, bitter flurries, but it had turned much

colder. The farm on the hill stood out - white roof

against a dead grey sky - like some surrealist painting.

That's where the road is, Mike assured himself grimly.

It's a long way.

A thin, icy wind moaned fitfully in the tops of the

cedars. Occasionally it descended to cut indifferently

at their numb faces. They continued in silence.

* * *

A waxwing fluttered across the stream, almost hovering

as it twisted to snatch a fly from the air. Mike

snapped out of his reverie - the hatch had started.

He had already tied on his Isonychia imitation. He'd

been experimenting with cut-wing, upside-sown pattern,

and had found that, for the bigger duns, they were very

effective, especially in sparse hatches.

The waxwing made another sortie - and another. This time,

Mike saw the big dun rising steadily against the evening

sky. He shifted to a kneeling position on the gravel bed

at the tail of the run. The surface upstream was burnished

in the afterglow.

The first rise came almost under his nose. He didn't really

have to cast - just an inelegant combination of a dangle and

a flick. The trout hit it almost immediately and dashed

downstream into the riffle. As quickly as he could, he

brought it back towards him. It wasn't big - under twelve

inches - and it didn't have much of a chance against the

4 lb. leaders, but it was a well-fed, tough, wild brown,

and it gave a creditable account of itself. Its flanks

glistened gold and green as he reach down the leader to

twist the hook free. It held in the shallows for a few

moments, but as soon as he made the first cast to dry

his fly, it shot away towards the other bank.

He settled back to watch the pool, which had not been

much disturbed by his capture of the small brown. In

the west, the sky gradually changed from gold to a cool,

translucent green. Above him the first stars began to

appear. The waxwings vanished.

The reflection on the run was much dimmer, but still bright

enough for him to see the rise clearly. It was tight

against the log cribbing. Mike knew there was at least

one very big brown in the run. He's seen her on a number

of occasions during the summer, by lying down on the

cribbing and peering through a gap in the logs into

the deep hole beneath - and on one windy June afternoon

he was sure he's risen and missed her. She was well

over twenty inches long.

This rise had the heaviness and deliberateness of a big

fish. He felt the old familiar quickening of his pulse.

Steady - take your time.

The fish rose again. It was a good fish. Carefully, he

false cast, and dropped the big fly a foot-and-a-half above

the fish. It dragged almost immediately. He cast

again - and again it dragged. It was a familiar

pattern - the eddies were so unpredictable. It took

infinite patience. On the eighth cast he managed a

good float. The trout took it in a heavy swirl.

He struck and felt the weight, then the first savage

plunge for the safety of the logs. No finesse

here - just brute strength and luck.

The fish turned suddenly, bolted towards him, and erupted

out of the shallow water almost in his face. Frantically,

he handlined in the slack. When he tightened, the fish

was still on. Incredibly, it was holding in the centre

of the run, well clear of the logs on the far bank.

Almost as if it's waiting for me.

As if in answer, the fish surged upstream. Mike gave it

line. Then, as soon as it reached the head of the run,

it turned and headed back towards him again. This time,

however, when he's taken in the slack, the line tightened

against something solid and unyielding. It pointed

directly into the log cribbing. Although he knew it

was futile, he released the tension on the line for

a couple of minutes, then tightened on it again. But

it was stuck just as solid as before. He pointed his

rod tip at the logs and pulled on the line until the

leader snapped.

Shaking a little, he rose to his feet and reeled in

his line. The reflection in the pool was gone.

Ah, well, he rationalised. At least I hooked it.

Maybe it'll still be there next year.

Beneath the logs, the trout lay with gills working.

Beside her, the remains of the leader were wrapped

three times around the steel T-bar, the broken end

floating freely in the water. ~ CM

We thank the

Canadian Fly Fisher for re-print permission!

| |