Lake Ontario Chinook: Small Stream Tactics

By Chris Marshall, Photos By Glen Hales

Fishing for salmon and migratory trout in the tributaries of Lake Ontario's north

shore is unique, in that there are no large rivers with significant runs.

Moreover, all of them lie west of Trenton. There are tributaries at the

east end, but all are warm water streams. A number of these have incidental

runs of both trout and salmon, and there is some evidence of limited spawning

success of chinook in at least one of them, but the for the fly fisher

the pickings are sparse and unreliable at best. The two largest north

shore tributaries, the Trent (which is huge) and the Moira, both of which

run into the shallow, warm waters of the Bay of Quinte rather than directly

into the lake, are among these. There are also incidental runs in some

of the outlets to Lake Ontario around the shores of Prince Edward County.

However, all the tributaries with significant, self-sustaining runs of

migratory salmonids are located west of Trenton and all are small.

Fishing such streams is very different from fishing the big waters of the tributaries

of the upper Great Lakes, especially for fish as large as chinook. In

some ways, it's easier, for unless the water is running high and stained

from heavy rains, the fish are very visible even in the deeper pools.

Consequently, sight fishing for them is a breeze. However, in these conditions,

they spook easily, and playing big fish in such cramped quarters is less

satisfying than it is the big rivers. But it has its own unique charm

and challenge.

Every species of migratory trout and salmon which inhabit Lake Ontario can be

encountered on the north shore tributaries in the fall. Chinooks, which

produce the heaviest runs, start entering the streams as early as the

middle of August, peak in September, with a few stragglers as late as

the beginning of November. These are followed by coho in September. There

are far fewer of these than chinooks, which is a pity, as they keep their

condition much longer, with vigorous fish available into December. Brown

trout also start showing up in late September and a few will hang around

after spawning on into November. The rainbows, which don't have the same

urgency as the other species (which are all fall spawners) will start

showing up at the mouths and the lower reaches in November, but very few

will move any distance upstream until early spring. Mixed in with these

will be a sprinkling of pink salmon and, on a few streams where they've

been stocked, Atlantic salmon. October also brings in a good number of

lake trout and a few of the rare north shore coaster brook trout, but

as these are out of season at this time, they can't really be counted

as part of the legitimate fishery. Rain plays a major role in the timing

of the runs, as all species tend to hang around at the mouth and move

upstream during post-rainfall freshets. Rainbows, for instance, will even

move back and forth between lake and stream as the flow waxes and wanes.

The primary focus of this feature is on chinooks, but the gear and tactics

described, apply to the other species with only minor modifications.

Chinook Streamcraft Strategies

While chinook will run upstream during the day if the water is high and stained,

under normal water conditions, they prefer to move at night. Many of the

fish that have made a nocturnal move can be found holding in riffles and

shallow runs early the following morning. However, once they've been disturbed

by anglers, especially those chucking heavy hardware at them, they take

refuge in the deeper pools. When chinook are holding in pools they're

harder to target than when they're holding in shallower water. It's harder

to track the fly visually in the deeper water of pools, and, because the

fish are more densely packed, the chance of inadvertant foul-hooking is

increased significantly.

While chinook will run upstream during the day if the water is high and stained,

under normal water conditions, they prefer to move at night. Many of the

fish that have made a nocturnal move can be found holding in riffles and

shallow runs early the following morning. However, once they've been disturbed

by anglers, especially those chucking heavy hardware at them, they take

refuge in the deeper pools. When chinook are holding in pools they're

harder to target than when they're holding in shallower water. It's harder

to track the fly visually in the deeper water of pools, and, because the

fish are more densely packed, the chance of inadvertant foul-hooking is

increased significantly.

This means that it pays to get to the stream at the crack of

dawn if you want to fish in optimum circumstances.

Techniques

Let's assume that you're an early bird and you've found a pod of chinook holding

in a shallow run. You should position yourself directly opposite or just

downstream from them. Get as close as you need to be so that you can see

your fly as it drifts or swings downstream. If you move carefully and

quietly, you should be able to get as close as 15 feet to them, but if

you can manage from 20 or 25 feet away, so much the better.

The composition of the pod and how much they're involved in

spawning or pre-spawning will determine how you'll tackle them.

When chinook first enter the stream, they're more or less

randomly mixed, but they quickly form into groups

of several males with a single female. Once this has happened, the males

are very susceptible to a jazzy, in-your-face streamer, which they'll

clobber as a potential challenge to their virility.

Therefore, check the fish in the pod carefully. Males have a somewhat longer head

than females and a pronounced kype. They also tend to engage in typical

male behaviour chasing each other and jostling to be first to mate. If

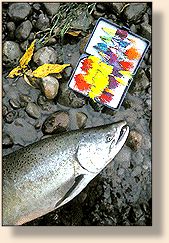

this is what's going on, tie on the most offensive streamer in your box

and swing it across and downstream. You'll get attention from at least

one of the males possibly from all of them.

Both males and females can be tempted, whether they're in a spawning group

or not, with a dead-drifted fly, triggering their instinctive feeding

response with a fly drifted repeatedly across their noses. This is where

it's essential to be in a position from which it's possible to observe

the fly as it drifts and the movement of any fish which might take it.

Simply watch the drift and when you see a mouth open and close on the

fly, set the hook. As chinooks will eat the spawn of other chinooks, egg

patterns work well in these circumstances, but other patterns such as

Spring Wigglers and Woolly Buggers are also effective. Patience is essential

here, as it usually takes repeated drifts to induce a take.

If you've arrived at the water after the fish have been spooked into the

deeper pools, you'll find that they're less willing to hit a fly. In the

deeper water, it's also more difficult to detect a take. Nevertheless,

the same basic techniques apply, it just takes a bit more patience and

concentration.

Hanging in There

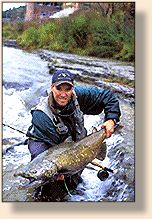

Chinook are big fish: the average size is around 20 pounds and

many will approach 30, with the occasional 30 plus specimen.

When you hook one of these on a small stream, it's very different

from hooking one out in the lake or on a river-sized tributary.

Most fish simply head downstream for the lake.

On a small stream (most of which have lots of bends an prolific streamside

vegetation), you have to follow, frequently at a run, when a fish roostertails

through the ubiquitous alder-fringed bends. This means that felt-soled

wading boots are essential to avoid slipping as you rush through slippery

bedrock and boulders.

On small streams, hooked chinook rarely, if ever, jump. However, if you happen

to foul hook one (a regular occurrence when they're packed tight in pools),

prepare for fireworks, especially if you've foul-hooked it in the tail.

Gear

Because you're targeting big fish in small streams, it's necessary to have gear

which is sturdy enough to stop fish quickly. A 9 weight outfit and a rod

with lots of backbone is ideal. Because the streams are shallow, a floating

line is all you need. It's not necessary to have lots of backing, as you'll

follow the fish on foot. I've never had a small stream chinook take me

into the backing. Because chinook do not spook easily, there's no need

for long, fine leaders and tippets. Four to five feet of 10 pound mono

is quite sufficient. On the few occasions where it's necessary to get

the fly down deep, shot pinched on the leader will do the trick.

~ Chris Marshall

Because you're targeting big fish in small streams, it's necessary to have gear

which is sturdy enough to stop fish quickly. A 9 weight outfit and a rod

with lots of backbone is ideal. Because the streams are shallow, a floating

line is all you need. It's not necessary to have lots of backing, as you'll

follow the fish on foot. I've never had a small stream chinook take me

into the backing. Because chinook do not spook easily, there's no need

for long, fine leaders and tippets. Four to five feet of 10 pound mono

is quite sufficient. On the few occasions where it's necessary to get

the fly down deep, shot pinched on the leader will do the trick.

~ Chris Marshall

Credits: From the Fall 2002 issue of The Canadian Fly Fisher.

We greatly appreciate use permission.

|