Garpike

By Chris Marshall

Fishing the Flats: Northern Style

I stand motionless, the warm water lapping around my knees.

Twenty feet from me, three grey shadows slide slowly just

beneath the surface, cutting at an angle which takes them

slightly away from me. I force myself to relax as I pump

out line: one false cast, two, three; and the fly drops

just beyond and ahead of them. I let it sink for a moment,

then start the retrieve.

Pull, twitch, pull, twitch.

One of the shadows breaks from the others, following the fly,

moving to intercept it. It closes. I speed up the retrieve.

The shadow moves faster. It strikes. I drive the hook home.

The rod jars in my hand and a fish erupts from the water-lean,

metallic, sickle-shaped.

Some tropical salt flat? Far from it. I'm fishing on the Bay

of Quinte close to downtown Belleville, Ontario. The species

of fish I've hooked is prolific in south central Canada, yet

it is one of the most ignored by anglers-especially by fly

fishers.

Why? In some cases, such as the trout-rich western provinces,

it's because there are so many opportunities to fish for trout

that fly fishers fortunate to live there aren't driven to seek

out alternatives. But here in southern Ontario, except for a

few tailwaters and spring-fed creeks, the trout fishing gets

pretty tough in the dog days of summer. Consequently, this is

when most of us confine our trout fishing to dawn and dusk,

shifting our focus to warm water species, particularly bass

and pike.

However, we've been slower to target some species than others.

Some species, for instance, don't readily take flies; some don't

offer much of a challenge; some don't put up much of a fight.

But, some are ignored because they've always been ignored by

the majority of spin, bait, and fly fishers alike. Garpike

fall in this category. Perhaps it's because it can be difficult

to get them to hit; they have an infuriating tendency to follow

a lure or fly, batting it with their long noses, or because,

when they do take, the hook often fails to hold in the bony jaw.

However, I suspect the real reason is simply a matter of perception.

Anglers just haven't bothered much with fishing for gar in the past,

so we don't bother much with them now. It's a pity, for they offer

a unique and challenging experience for fly fishers.

What makes fly fishing for gar unique, is that it involves

stalking the quarry while wading shallow flats. While it's

not exactly like wading tropical, saltwater flats for bonefish,

it has many similarities-sightfishing, bright sunshine, warm

water up to your knees. Besides the lack of the salt smell,

the main difference is that rather than feeding on the bottom,

gar usually lie motionless or move very slowly just beneath

the surface. They also provide good sport. For while they don't

make the long, blistering runs typical of bonefish, they

frequently take to the air.

Thousands of lakes in southern Ontario and Quebec offer ideal

gar habitat. What you need to find are expansive shallow, flat

areas which remain relatively free from weed throughout the

summer. These flats warm quickly and by late spring are full

of gar. Although the water of the average Canadian lake does

not have the crystal clarity of the Caribbean salt flats,

it's clear enough to spot fish in depths up to at least

three feet. It's also warm enough to wade bare-legged from

June through to September and the bottom is firm enough

to make wading easy.

Gar are relatively easy to spot, as they frequently lie just

beneath the surface in open water. They're also easy to approach

without spooking; with stealthy wading, it's possible to get

within fifteen feet of them, especially if they're in gaps

in the weeds. Therefore, casts of more than twenty-five feet

are rarely necessary. It's also relatively easy to get them

to follow a fly. However, hooking them is a bit more difficult.

Sometimes they'll just follow without touching it; other times

they'll chivvy it without actually grabbing it. The most

effective presentation is a retrieve at right angles to

the axis of the fish about a couple of feet from its nose.

This frequently induces a sudden ambush, with the fly taken

crossways.

Summer Morning: Bay of Quinte

Let me take you to my local garpike hotspot. Although it's

within the city limits, the shoreline is quite wild and

undeveloped. It's early morning on a clear day in August;

the sun has just cleared the horizon; the air is still.

I'm with our photo editor, Glen Hales, whose youthful, sharp

eyes are much better than mine for spotting fish. We push

through the cattails at the edge of a wide bay. Here the

shallows extend a couple of hundred feet out from the shore.

The face of the water is absolutely flat, calm, unruffled by

wind. Perfect conditions.

Quietly, we wade out into the shallows, the water swirling

around our calves like warm milk. Thirty feet to our left a

carp rolls lazily. We separate until we're about twenty feet

apart from each other. Slowly we make our way westward, our

backs to the rising sun, our eyes fixed on the water, questing

for the unmistakable, lean shapes of gar.

With the sun behind us, we can see every detail through the

knee-deep water: the bottom is laden with broken fragments

of limestone with occasional larger rocks, pockets of silt,

and small clumps of weed. Everywhere there is movement:

shoals of minnows skittering in unison just beneath the

surface; rock bass and pumpkinseed lurking at the edges

of the larger rocks and under the skirts of the weed clumps;

a pod of five carp cruise like bronze-blue dirigibles along

the edge of a deep channel between us and the shore.

As usual, Glen is the first to spot them. He shouts, "Right

in front of you! About forty feet and to your left."

I stop moving and look where he's pointing. I strain my eyes

for a few moments; then I see them.; three gray/yellow shapes

lying motionless in a deeper pocket. They're at right angles

to me, their noses pointing towards the shore. Two are

relatively small, but one is close to three feet long.

I pull the brim of my hat down more securely and clamp my

teeth on my pipe - essential preliminaries to casting. It's

not a long cast, but it has to be delicate. In these shallow,

calm waters, even gar can be spooked. I drop the big streamer

fly about two feet ahead of leading gar (one of the two smaller

ones) and about five feet beyond it.

The gars have not moved. I point the rod tip at the fly and

begin the retrieve. Stripping with my left hand, I make the

fly dart and flutter towards the gar, cutting into its field

of vision. Two feet away - and it begins to move - slowly

at first - gradually, almost imperceptibly, accelerating - turning

to intercept it. This is the crucial part: there is a powerful

temptation to slow down the retrieve to let it catch the fly.

That would be a mistake, as this can cause the gar to lose

interest and turn away. Instead, I speed up the retrieve, and,

seeing its intended prey apparently escaping, the fish lunges

ahead and grabs it.

I heave back on the line with my left hand to set the hook.

And the gar is suddenly out of the water. Two more aerial

lunges. Then everything goes slack. The line catapults

back towards me, and I duck to avoid the fly. I look

apologetically at Glen. He laughs. In front of me the

surface still heaves from the violence of the encounter.

I reel in, inspect the fly and the shock tippet, shrug wryly,

and prepare to continue my stalk along the shore.

Losing gar is not unusual. It's hard to set a hook in their

hard, bony snouts. If you manage to hang on to one out of

three, you're doing well. Luckily, there are plenty of them

on the flats, and even after they've been disturbed, they

don't move far away and they usually settle down sufficiently

for you to have another go at them on the way back.

So, I resume my sneaky wade along the shore. By this time,

Glen is a well ahead of me and a good fifty feet further out

into the bay. Even as I watch, he stops and begins to cast,

targeting a fish he's seen inshore from him. I wait, hoping

for a chance at my turn for a laugh. But I hope in vain.

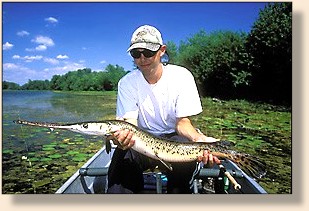

The fish hits, he sets the hook, and it holds. The gar gives

him four wild, tail-walking leaps and a couple of surging

runs and then it comes in, ready for release. That's the

way with gar; they don't fight long, but they do fight hard

and, usually, quite acrobatically.

As the sun rises higher and the day heats up, we continue

our hunt through the shallows, locating over twenty gars,

enticing follows from most of them, getting strikes from

about half, and landing six between us. By midmorning a

wind has arisen, ruffling the water so that spotting the

fish becomes increasingly difficult. We decide to call it

quits, well satisfied after three hours of intense action.

~ Chris Marshall

|