King Chinook

By Rob Brown

In Alaska and other American states with Pacific shores Oncorbynchus

tsbawytscka is the king. In Canada his majesty shares the name Chinook

with the dry wind that whips down from the Rockies bringing unseasonably warm

air to autumn days. In Skeena he is the spring salmon, named for the time of year

when the first of his numbers begin to appear in the river of the Kitsumkalums, Spring,

Chinook, smiley, king - whatever you call him he is the largest and strongest of the

Pacific salmon with a prominent place in the dreams of sports fishers.

Like other fishermen, I'd caught springs with bait and lures, but sitting under the

hot sun behind a forked stick watching a belled rod is more market fishing than

fishing for sport. Casting spoons from one spot, though more sporting than still

fishing, tends to be costly, and its still too sedentary a pursuit. For years I thought

about bringing those leviathans to a fly. I had read plenty of articles about the

exploits in Alaska, but these were invariably illustrated with pictures of fly fishers

straining as they hoisted ripe kings the colour of fire trucks. Salmon guarding

redds can easily be provoked to strike, but provoking them is like shooting

nesting birds. No knowledgeable, ethical angler does it. No, the trick was to

hook this fish when they were still clean and silver, new arrivals to fresh water.

In the summer of 1986 I set out after spring salmon in earnest. The first task

was to assemble the right tackle for the job. Big fish demand big rods, I reasoned.

In hindsight, I believe I should have purchased a tarpon, for the better leverage

these poles have, but a ten weight, 15-foot Hardy Spey rod was handing from

the wall of the local sporting goods store. Because nobody in Terrace [B.C.]

was using one at the time, and because it appealed to my iconoclastic nature,

I bought it and very nearly wore my arms out trying to cast it in what I thought

was the approved manner.

To complement the rod I purchased Hardy Marquis, Salmon #3, a giant winch

carrying a 40 yard double taper fly line and hundreds of yards of backing its

manufacturer claimed had a breaking strength of 30 pounds.

Mike Whelpley, who had been ramrodding the Kalum Project where some giant

Kalum Chinook are taken each year for enhancement purposes, told me his crew

had found a hulking male during a dead pitch, that even in its spent condition,

weighted over 70 pounds. Firmly attached to the hinge of its toothy jaw was a

number four Green Butt Skunk. So, in this anecdote was evidence that some

Chinook will take a fly, and, given the size of the fish, a relatively small fly at that.

I assembled an arsenal containing this pattern, a half dozen General Practitioners

built on three and five ought Atlantic salmon hook as well as a number of two

inches vinyl tube flies in Green Butt Skunk dress, but with a few thin strands

of pearl Mylar lashed on under their polar bear wings. Since the regulations

forbid trebles, I broke from the British cannon and armoured them with needle

sharp 2/0 bait hooks, choosing the red plated models in keeping with the red

tail demanded by the recipe for Skunks.

The next hurdle was to find a spot where migrant Chinooks stacked up to

marshal energy for the rest of their journey, excluding those spots where the

current is simply too heavy for the fly. Unfortunately, Chinook often favour

these heavy flows. I went through a list of rivers using a process of elimination:

the Skeena was simply too big, the Chinooks, unlike their cousins, generally

preferred to swim too far out in the river; the beaches of the Kalum, home

of the biggest springs, where underwater during the peak migration of Chinook;

it was the same situation on the Ecstall River; the Lakelse simply had too few

fish - and most of the river was closed to fishing anyway. All of which left the

Zymoetz. It, after all, hosted a strong run of springs, and, provided it wasn't

too filled with glacial flour, had plenty of inside corners and long runs suited

to fly fishing. Moreover, I remembered a day when Bill Burkland of Kitimat

hooked a steelhead and a small Chinook on his six weight cane rod with a

Muddler Minnow at the end of a floating line.

Finlay was skeptical. Gene Llewellyn downright disbelieving when I met them

at Baxter's Riffle, showed them my outfit and told them my mission. It was a

hot day. For the Zymoetz the water was clear, affording me two and a half

feet of visibility. "If you stand in the river up to your knees and you can still

see your feet, then it's fine for fishing," Finlay declared. "That's what Ted

Rawlins used to say."

We didn't wait long for a fish to roll. I could see they were milling around

where a strand of gravel lay at the rail of a rapid creating 50 yards of slower

water behind it. The line was one of those fast-sinking models, 12 feet long.

I'd attached a short leader of 15-pound and one of Colonel Drury's Orange

prawns. In short time I'd ambushed my first Chinook. It hit hard, setting

off a large splash.

"We got one!" Gene yelled to Fin.

The fish proved to be about 15 pounds. There were no jumps, just strong

determined runs. It was much stronger than a steelhead of the same size.

"They're stronger, pound for pound," Gene agreed when I made this observation.

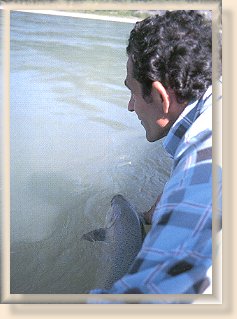

For a week I fished this ambuscade, beaching 12 salmon. The largest was the

most memorable. A little over 50 pounds he pulled over half a mile from Baxter's

to the Old Bridge. Twice he came within inches of spooling me, once running the

backing all the way to the arbour knot. For all the excitement, there was something

distasteful about the episode. The fish was on for an awfully long time before

I could get him ashore. The fishing was more like work than sport. If I could

somehow dissuade salmon of over 20 pounds from taking the fly, if the places

to fish for them weren't so few, and the right conditions so hard to find, I'd

still go out after them each summer. ~ Rob Brown

Credits: From Skeena

by Rob Brown. We thank

Frank Amato Publications, Inc. for use permission!

Our Man In Canada Archives

|