|

Thibodeaux's wife bought a new book entitled What

Twenty Million American Women Want. Thibodeaux

saw the book's title, then grabbed the book out of her hand and

started thumbing quickly through the pages. Furious, his wife said,

"What in the world are you doing?"

Thibodeaux replied, "I just want to see if they've got my name

spelled right."

How often do you wonder about names of flies? Today, you have

to have a lot of chutzpah to name a fly after yourself. So, let's take

a second to look at some famous flies from the past and their fly tyer

creators.

Isacc Walton describes the Woolly Worm (in 1653) but Russel

Blessing of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania claims the Woolly Bugger

from a fly he created in 1967.

The John (Jock) Scott created in the 1850s by Jock Scott.

The hare's ear is attributed to James Ogden in the 1880s

The Adams fly was designed by Len Halladay of Michigan in 1922.

The Coachman was created by Tom Bosworth, who drove

the coach for Queen Victoria. Then came the Royal Coachman,

in 1878, by John Hailey, in New York city, followed by the Royal

Wulff created in 1930 by Lee Wulff.

The Dark Cahill was named after Dan Cahill in 1884.

The Grey Ghost was the creation of Maine's Carrie Stephens

at the turn of the 20th Century.

The Mickey Finn, Blue Dunn, Black Gnat, Bitch Creek

and Blue Wing Olive have unknown originators in the

American west.

The Humpy is credited to Jack Dennis of Jackson Hole,

Wyoming.

The Irresistible is attributed to Harry Darbee of New York

in the 1930s.

The Renegade was claimed by Taylor Williams of Sun

Valley in the 1930s.

The Klinkhammer is by Dutchman Hans Van Klinken.

The Muddler Minnow came from Dan Grapen

of Minnesota.

Winnie Morawski of Scotland produced a Tube Fly in 1945.

Griffiths Gnat was created George Griffith in the 50s.

The Pheasant Tail Nymph came from Frank Sawyer

of England in 1958.

The Zonker was invented by Dan Byford.

The Clouser comes from Bob Clouser.

The Deceiver comes from Lefty Kreh

The Stimulator was popularized (if not originated) by

Randall Kaufmann in the 70s.

Many soft hackle flies were created or recreated

by Sylvester Nemes in the mid 70s.

The Elk Hair Caddis was by Al Troth in 1978.

The foam diver is by Skip Morris from the 1990s.

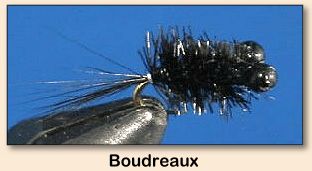

The Boudreaux came from Ray Boudreaux after Y2K.

Okay, what was the purpose of that exercise? Note that names

of creators do not have to, and rarely do, accompany a fly. If your

living comes from fly fishing, you are going to stick your name on

anything that comes off of your vise and hope it adds to your cache.

Dan Bailey apparently insisted the Lee Wulff put his name on his flies,

and fame followed. For the rest of us, we will remain in obscurity like

the Winnie Morawskis of this world.

I took it upon myself to insist Ray Boudreaux to call his fly The

Black Boudreaux because I am addicted to its catch-everything

ability, because it sounds like a Louisiana fly should, and because

Ray couldn't think of a better name. Walking around various FFF

Conclaves with some of the best fly tyers in the South, I have no

hesitation is asking "What do you call that beautiful fly?" and the

usual answer is "some kind of bug." Curiously, this concept of

humility is completely foreign to on-line pattern posters. Take a

trip around Internet pattern sites and you will find perhaps the John

Doe Bad Ass Woolly Bugger, which looks like a thousand other

woolly buggers except this one has a color combination Doe once

saw on the ceiling of a disco (where three sheets John was lying on

the floor at the time). New fly tyers are particularly susceptible to

naming their creations, despite their less than stellar craftsmanship,

after themselves. Maybe the sloppier a fly the more it reflects its

maker.

True, there are times when a fly that looks like someone tied on a

hairball from Joe the Rag Picker's ratty cat it will outfish anything

else on the river. My daughter's pets shed (this is no lie) two vacuum

bags worth of hair a week. I have yet to develop the sled dog muddler

or the orange tabby prince, but some day. Chances are, if they are

unique, I may name them after Ozzie and Yogi (my daughter is a

baseball fan), but more likely they'd end up the wet dog wiggler or

feral floater.

Meanwhile, I will take responsibility for naming the Boudreaux.

There was a point in time when someone said to someone else:

"Why the hell didn't you tell me about sliced bread?" Now let

us suppose that the someone else had been showing up every

day with a sliced bread sandwich and was chowing down on

his version of a BLT when everyone else was ripping and tearing

off hunks from a baguette. You might think maybe, just maybe,

someone should have noticed.

Since it's creation, I have been singing the praises of the Black

Boudreaux (which is sometimes chocolate, or olive or tan.)

Perhaps if it was a secret, fly fishers would pay more attention.

Boudreaux's cousin Chauvin and the miller's daughter, Angelle

were to be married. As the big day approached, the bride and

groom grew apprehensive. Each had a secret problem they had

never before shared with anyone. So…Chauvin asked

Boudreaux for advice. "Boudreaux," he said, "I am deeply

concerned about the success of my marriage. Angelle is so

delicate and I have very smelly feet, and I'm afraid that she

will be repelled by them."

"No problem," said Boudreaux, "all you have to do is wash

your feet regularly, and always wear socks, even to bed."

Chauvin thought this seemed like a workable solution.

At the same time, the bride-to-be, explained her problem to,

Madeline, her maid of honor.

"Madeline," she said, "When I wake up in the morning my breath

is truly awful."

"Girl friend," Madelin consoled, "everyone has bad breath in the morning."

"No, you don't understand. My morning breath is so bad, I'm

afraid that Chauvin will not want to sleep in the same room with

me."

Madeline said simply, "Try this. In the morning, get straight out of

bed, and head for the bathroom and brush your tongue where bad

breath grows. The key is, don't say a word until you've brushed.

Not a word." And … Angelle thought it was certainly worth

a try.

The couple were married and each one remembered the advice

they had received, Chauvin with his perpetual socks and Angelle

with her morning silence. They managed quite well…until

about six months later.

Shortly before dawn, Chauvin woke with a start to find that one

of his socks had come off. Fearful of the consequences, he

frantically searched the bed.

This woke Angelle who, without thinking, immediately asked,

"What on earth are you doing?"

"Oh, no!" Chauvin gasped, "You've swallowed my sock!"

Fly fishing secrets are too good to keep. The problem is,

shared secrets are too often misunderstood or simply ignored.

Such a secret is the Black Boudreaux. At the risk of sounding

like a broken record, I again proclaim the excellence of this

simple and incredibly effective fly that most of my readers ignore.

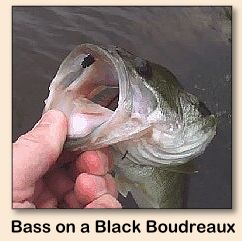

Take August, for example. Following several hours of torrential

downpour from Hurricane Ike, the lake behind my house rose

about six inches. Fresh water poured in from several French

drains leading to the lake. Fish could be seen actively feeding

along the shoreline and soon many large bluegill and small bass

fell prey to a chocolate Boudreaux. A large swirl attracted a cast

and the popper from which the Boudreaux dangled disappeared

in a blur. A hard hook set preceded a full ten minutes of fight as

the soft 7'-3wt. struggled to handle the leaping, pulling, twisting

four pound bass. When the big predator was worn down,

examination revealed the chocolate Boudreaux firmly impaled

about an inch back in the top of his mouth. Unfortunately, no

camera was handy, but a few more fish followed, none that size,

although a pair of 9" bluegill were worthy foes.

The outing ended as a large something-or-the-other broke

the 6# tippet and left with the Boudreaux. Two weeks earlier

green sunfish battled each other in a Florida pond for a change

to eat a grey Boudreaux and a week before that Houston bass

and sunfish attacked the black Boudreaux furiously. In July,

Colorado rainbows and browns took the fly. Some fly!

The outing ended as a large something-or-the-other broke

the 6# tippet and left with the Boudreaux. Two weeks earlier

green sunfish battled each other in a Florida pond for a change

to eat a grey Boudreaux and a week before that Houston bass

and sunfish attacked the black Boudreaux furiously. In July,

Colorado rainbows and browns took the fly. Some fly!

The Black Boudreaux

created by Ray Boudreaux (Acadiana Fly Rodders)

Hours of fishing lakes and ponds have proven that no new pattern

is more effective overall than the Black Boudreaux. Using this

pattern, practically all local warmwater species have been caught,

including panfish, bass, sacalait, shad, gar, catfish and choupique

(not a fun time for fly equipment there). The fly is easy to tie and

is fished either alone or as a dropper. It is a small fly (size 14) and

barbeless hooks are highly recommended. Size and color are

important, and while black has proven to be the best, olive and

chocolate (see sacalait photo) work as well. This recipe deviates

slightly from the original, but the manner of tying the fly shown below

is intended to accurately reflect Ray's pattern concept and create a

durable fly that will withstand many fish. A fly with a tinsel underbody

works better than without and super glue the hackle to the tinsel or it

can unravel after a few fish. A drop of fish attractant or WD40

disguises the scent of glues.

Hook: Size 14 scud hook (Dai-Riki #135, Eagle

Claw L055, Mustad C49S, Tiemco 2457, Cabelas Model 25,

or similar)

Thread: Flat waxed nylon.

Eyes: Small black bead chain.

Tail: 6-10 hackle barbs.

Hackle: Dry fly saddle hackle.

Underbody: Tinsel over thread.

1. Wrap the hook shank from the eye to the start of the

bend with thread. Using a scud hook produces a better

shaped (curved) fly and provides more hookups. Most

scud hooks are slightly offset, which is acceptable. Flat

waxed nylon thread is used for durability.

2. Tie in the tail at the beginning of the hook bend with about

¼"-3/8" extending past the hook. Biot or maribou can

also be used, but simple hackle barbs work best. Bring the

thread forward to the hook eye.

2. Tie in the tail at the beginning of the hook bend with about

¼"-3/8" extending past the hook. Biot or maribou can

also be used, but simple hackle barbs work best. Bring the

thread forward to the hook eye.

3. Tie on the eyes immediately behind the hook eye with a

figure eight wrap and put on a tiny drop of super glue on the

wraps. (Small black bead chain is available from Hobby

Lobby.) Bring the thread back to the start of the tail.

4. Tie in stiff dry fly saddle hackle (with the shortest barbs

possible).

5. Tie in a strand of tinsel and bring the thread forward to

the eyes. Wrap the tinsel to completely cover the thread

on the hook shank and tie off behind the eyes.

6. Put a very light layer of super glue on top of the tinsel.

7. Tightly palmer the hackle up to the hook eye. Tie down

and clip the excess.

8. Whip finish around the eyes.

9. Trim the hackle barbs all around the shank to a length of about 1/8".

10. Put a small drop of Hard as Nails on the whip finish between

the eyes. ~ Bob

About Bob:

Robert Lamar Boese has fly fished for five decades. He is an

environmental negotiator, attorney and educator who has provided

environmental legal services for more than thirty-three years including

active duty with the U.S. Coast Guard and Department of Justice. He is a

well known fly tyer with several unique patterns to his credit. He has

developed and authored federal and state regulatory programs

encompassing a broad spectrum of environmental disciplines, has

litigated environmental matters at all levels of the federal and state

court systems, and is a qualified expert for testimony in environmental

law. He has authored over 60 published text chapters, comments or

articles on environmental matters, is a member of the Colorado, District

of Columbia and Louisiana Bar Associations, and is a certified mediator.

In addition to his legal practice, Mr. Boese has been a high school

teacher, an associate professor of Environmental Law and Public Health,

has authored numerous fiction and sports publications, and is a softball

coach and nationally certified volleyball referee. He is the president

of the Acadiana Fly Rodders in Lafayette, Louisiana and editor of

Acadiana on the Fly. He has been married for thirty years and is the

father of two fly fishing girls (25 and 21). For additional information

contact: Boese Environmental Law, 103 Riviera Court, Broussard, LA 70518

or call 337.856.7890 or email coachbob@ymail.com.

|