|

[Generic flies are simple-to-tie patterns that a novice tyer can

accomplish and which requires less

than four dressing components.]

Okay, eavesdropping is a bad habit. But there I am with a

mouthful of biscuits and gravy when, wafting over the whoosh

of the 60s air conditioner, comes a fly fishing conversation.

Don't know the speaker, can't say if he knows a sculpin from

a BWO, or if his roll cast looks like coils of garden hose, but I

listen because he caught fish – which qualifies him as an

expert. At least he says he did, and eavesdroppers chronically

suspend reality to believe what they hear. So, like one of the fish

of his tales, I am hooked.

Sipping water to look inconspicuous, I lean toward him, silently

cursing other diners for clanking forks on their plates or having

the audacity to hold conversations while I'm trying to overhear

Mr. Caughtfish. In suspense filled tones he explains yesterday's

wind and weather conditions, which everyone listening already

knew, but he's the type that needs plenty of backdrop for his story.

Paddle stroke by paddle stroke he drags us through the cypress

trees until we reach a small opening between cattails and lily pads

where his fly barely touches the water before it is engulfed by a

gigantic bluegill. Cast after cast he drags huge panfish from that

single hole without ever a missed fish or snagged limb. He describes

incredible strikes and vicious attacks on the only fly he used, the

greatest pattern since forever, it was a.…

The waitress asks if I need more anything and I jump a foot.

She leaves, wondering why all the nuts sit at her tables and

why I've allowed crust to form on my cooling gravy.

Still shaken, I actually drink some water, wishing it was something

more spirited and I lean even further. Anyone looking would think

my back had gone out, but all I care about is that the tale is

continuing. He has somehow moved from his honeyhole to another

open area where bluegill are dueling each other to jump on his line.

His ice chest is bursting full of plate-sized fish, and all of this thanks

to a single mystery fly. He regales his tablemates with more and larger

fish caught until he finally took a breath and ate his pancakes. And then

one of his tablemates starts another story.

"Wait!" I want to yell, "It's not your turn! What fly pattern?" But the

next fisherman starts a tale of woe, filled with wasted hours and empty

creels, all of which sounds too familiar. He's just using the wrong bait,

declares Mr. Caughtfish and I see the waitress approaching. Desperately

I wave her off and, as she shrugs and looks to the sky for help that's

not coming, and behind me the mystery fly is revealed. I hear the

secret in a nervous dither that turns to disbelief. No, it's not possible,

I think. Stunned, I take a big drink of tepid water but, yes, it is true.

In the two square feet of shelf space that is Wal-Mart's entire inventory

of fly fishing equipment, Mr. Caughtfish found a sponge spider. He

bought two, yellow with whiterubber legs, but one is so beaten up he's

going back to get another. Figures it was about the best buck and a

quarter he's ever spent.

The bits of orange pulp in my juice has gathered to the top and

my gravy breakfast congealed to something resembling food

served in the military. I signal for the check and leave a healthy

tip, as if it would explain my insanity. Later, after hours of tying,

I still have not produced a spider I am willing to show in public.

And so I go to Wal-Mart, where, between dingy fly lines and

aged plastic fly boxes, I find a small rack of yellow sponge spiders.

I buy one and spend the next hours recreating it. And the more I

tie the more I am confused. Panfish, particularly bluegill, have well

recognized diets. Aquatic insects, insect larvae and crustaceans are

their primary prey. Vegetation, fish eggs, small fish, mollusks, and

snails and the occasional beetle or ant fill out the menu. Notice that

the list does not include specific reference to spiders. Why?

Terrestrial spiders and water are not a common pair. True, there

are water spiders that inhabit certain lakes and ponds, but, the real

question is "just how often does a bluegill see a floating spider?"

The answer is probably "never" unless a spider is blown out of a

tree and has the misfortune to land in the immediate vicinity of a

bluegill.

Then why is a sponge spider fly successful? The answer is: because

it doesn't look anything like a spider.

Consider the silhouette a real spider presents. First, a spider

has eight legs which splay around two oblong (sometimes tapered

but not pointed) shapes: (1) the abdomen or belly (also called the

opisthosoma) contains the heart, organs, and silk glands and (2) the

cephalothorax , the fused head and thorax (also called the prosoma)

contains the brain, jaws, eyes, stomach, and leg attachments. Do bluegill

count legs? Probably not, which would explain why spider imitations have

4 or 6 legs. Also, a spider's legs are quite long in relation to the torso and

have seven segments (of which we usually only notice three). Then why

do many sponge spider flies have short straight stubby rubber legs? Dunno.

Next, a spider has several pairs of tiny eyes located on top of the

cephalothorax. Creators of spider flies with a single pair of large

eyes on the sides of the thorax must know something I don't. Finally,

a spider has pedipalps which are feelers attached to the front of the

thorax that look like stubby legs, which we can only assume the

hook eye is supposed to represent, or at this point does it matter?

Terrestrial spiders that have the bad luck to be on the water have

a remarkable ability to walk on the surface film. They disturb very

little of the surface as they skitter back to something solid. Under

the best of circumstances, this is a very difficult action to accomplish

with anything heavier than a stiffly hackled dry fly, and certainly not

with sponge.

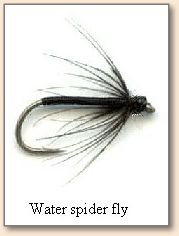

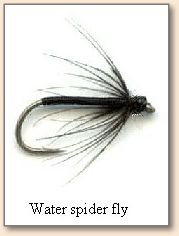

Note that soft hackles or other wet flies called "spider patterns" are

intended to represent the water spider (an aquatic species), and certainly

would appear to do so with more accuracy than floating varieties.

Which brings us back to the success of the sponge spider. Luck has as much

— often more— to do with catching fish as logic. What the facts

suggest is that a novice fisherman buying a sponge spider has the good luck

to purchase a generic insect fly, that represents nothing in particular, and

particularly not a spider. The sponge spider may look like a wasp, or bee,

or caterpillar, or beetle, or maybe like nothing in nature at all. Bluegill

probably don't consider that something that only sort of looks like

something to eat might be something else. It is the same inexplicable

attraction that makes spinnerbaits or stimulator flies work. Inexplicable,

as in can't be explained.

What we can presume to know is that luck is involved, and such

luck has to include something approaching the right size and color.

Even a carelessly delivered and retrieved fly that presents a tempting

profile can catch fish. Consequently, you would think that if the sponge

spider fly will work, so should any other reasonable insect imitation in

your fly box. Not so. The spider is so generic it defies bluegill senses

to determine if is something they don't want to eat. And, given the

choice, bluegill will chose to eat it.

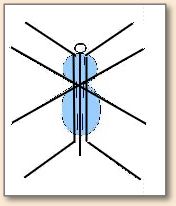

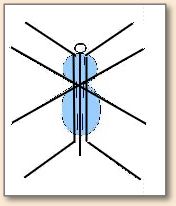

GENERIC SPIDER PATTERN

Hook: standard dry fly hook #8-14.

Thread: Flat waxed nylon (same color as the foam)

Body (abdomen and thorax): sheet (fun) foam.

Legs: round rubber.

1. Lay a layer of thread along the entire hook shank. This

serves to help gluing and to color the shank to match the fly.

2. (Optional for 8 legged version) Lay two round rubber legs

along the hook shank with about ½ in. extending past both the

hook eye and over the bend. Use a figure 8 pattern to tie

down the legs and give them a "V" shape.

3. Gently wrap over the shank the shank is completely covered

with thread making a smooth finish of thread.

4. Bring the thread to ¼ distance down the shank from

the hook eye.

5. Cut a small strip of fun foam (about 3/8") shaped like

a .22 long rifle bullet .

6. Put a light coating of Super Glue on the thread covered shank.

7. Lay the foam on the hook shank with the end of the

taper just past the bend.

8. Tie down the foam letting it bend slightly around the

hook shank. (You have now segmented the foam and

the tapered end will be the spider's abdomen.)

9. Take the thread straight under the foam to the eye of

the hook and tie down the foam at that point, making a

round shape between the first tie down and the eye of

the hook.

10. Trim off excess foam.

11. Move the thread (again under the foam) back to the

first tie-down location and using "X" technique tie in a leg

on either side of the foam.

12. Move the thread (under the foam) back to the eye

and whip finish and coat with Hard As Nails.

GENERIC WATER SPIDER PATTERN

Hook: 2X nymph hook #12-16.

Thread: Flat waxed nylon (black or brown).

Bead: colored to match thread

Legs: soft hackle to match thread

1. Put the bead on the hook and work to the eye.

2. Wrap the hook shank with thread in 3-4 layers

until a smooth thread body has been created.

3. Tie in a soft hackle and wrap 3 times.

4. Whip finish behind bead. ~ Bob

About Bob:

Robert Lamar Boese has fly fished for five decades. He is an

environmental negotiator, attorney and educator who has provided

environmental legal services for more than thirty-three years including

active duty with the U.S. Coast Guard and Department of Justice. He is a

well known fly tyer with several unique patterns to his credit. He has

developed and authored federal and state regulatory programs

encompassing a broad spectrum of environmental disciplines, has

litigated environmental matters at all levels of the federal and state

court systems, and is a qualified expert for testimony in environmental

law. He has authored over 60 published text chapters, comments or

articles on environmental matters, is a member of the Colorado, District

of Columbia and Louisiana Bar Associations, and is a certified mediator.

In addition to his legal practice, Mr. Boese has been a high school

teacher, an associate professor of Environmental Law and Public Health,

has authored numerous fiction and sports publications, and is a softball

coach and nationally certified volleyball referee. He is the president

of the Acadiana Fly Rodders in Lafayette, Louisiana and editor of

Acadiana on the Fly. He has been married for thirty years and is the

father of two fly fishing girls (25 and 21). For additional information

contact: Boese Environmental Law, 103 Riviera Court, Broussard, LA 70518

or call 337.856.7890 or email coachbob@ymail.com.

|