|

I have a season ticket on the wonderful Wharfe River

at Bolton Abbey in North Yorkshire which is only 20

minutes from home and one of the best rivers in that

county. Over the past couple of years this has been

my home for fishing.

Just recently I was fishing a particular section of the

Wharfe and I remember a rather special fish. I had just

made a perfect cast to my right which I knew would allow

the flies to sink in the water before swinging upwards

through the current. Making sure that my rod did not get

in front of my line I concentrated on the feel of the line

as it begun to swing across and upwards through the current.

Was that a touch? Did I perceive a small slowing of the

line? I pulled firmly, but not too hard, against the line

and felt the weight of something on the end. A fish exploded

through the surface. I had him. A 3lb brown trout.

I had seen this fish taking emerging Baetis mayflies some

20 minutes before. I had noted where he was laying and had

worked my way slowly down the run picking up a couple of

smaller fish on the way before I prepared to 'trap' him

with my flies.

The small 'spider' patterns that I had been fishing had

done their job again. Just as they had on the other dozen

or so fish I had caught that day. And there was still a

lot more fishing to be had yet. Why had I not used them

at home in Australia?

This season I have been concentrating on learning and using

the 'spider' patterns of northern England. The season has

now been open for 3 months and I have already fished more

than I would in a normal season. Due mainly to the fact that

work commitments have not been as intensive as normal.

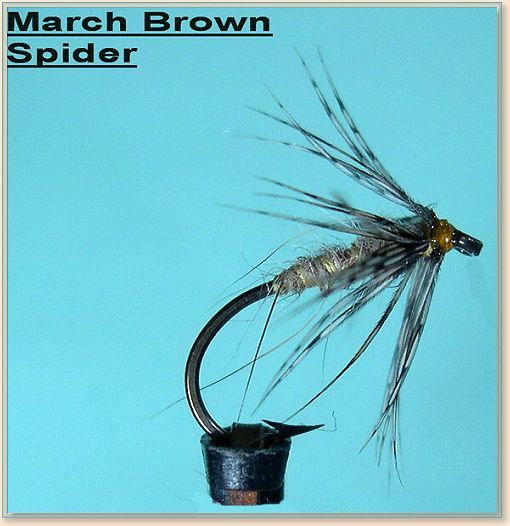

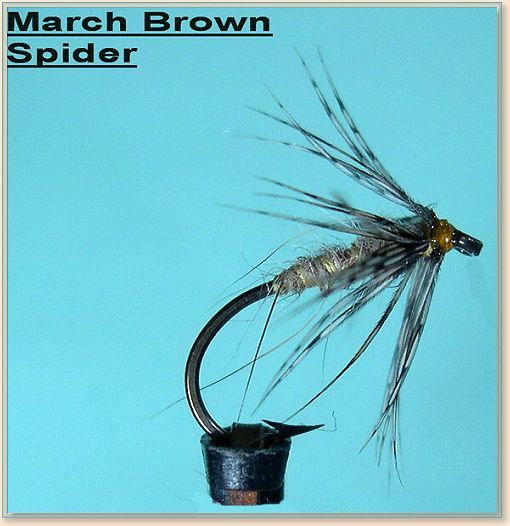

What is a 'spider pattern'? A 'spider' fly is defined as 'a

soft hackled pattern, rarely with wings'. These flies are not

intended to represent a natural spider. The term 'spider' was

probably inherited from Scotland and was a tradition made

famous by W. C. Stewart (more about Stewart later).

'Spider' patterns were used exclusively by the fly fishermen

of the northern parts of England for some time before venturing

further afield. Indeed, you do not see them very often in tackle

shops or featuring in fishing articles. These mediums of fly

fishing seem to dispense with the old traditional flies and

concentrate of the more modern fly patterns and their myriad

of variations.

Do 'spider patterns' work? When fished properly they are deadly

and if the weather conditions are right it is not unusual to

catch many fish in an outing. In a four-day period recently

where I was able to get out fishing each day and I had been

able to catch and release over 100 fish in a five-mile stretch

of Wharfe.

Soft hackled flies first appeared in the Compleat Angler

when Charles Cotton wrote his famous book in 1676. Indeed, it is

likely that they were around for some time before Charles Cotton

as the patterns and materials used at that time probably meant

that 'soft hackled' flies were in use even in the Roman occupation

period.

Apart from some writings by James Chetham in 1681, new works on

angling were almost non-existent for two centuries. Soft hackled

flies were again introduced to anglers in 1816 when G. C. Bainbridge

wrote The Fly-fishers Guide. Another 60 years were

to pass before three more valuable works featured soft hackled flies.

W. C. Stewart wrote The Practical Angler; W. H. Aldham

A Quaint Treatise on Flees and the Art of Artyfichall Flee

Making in 1876; T. E. Pritt Yorkshire Trout Flies

in 1886 (which was re-titled North-Country Flies in a

later edition). All these books featured extensive writings on soft

hackled flies. But in 1857 the greatest influence on using these

patterns in England occurred. W. C. Stewart was a renowned fly

fisherman from the Scottish Border area and it was Stewart that

put 'spider' patterns in the fly box of all the north of England

fly fishers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

It was to be another 80 years before a major writing on the use

of soft hackles was to emerge. During that time there were many

references to these patterns. Macintosh, Ronalds, Skues and others

all reference the use of these patterns and the characteristics

of soft hackles.

In 1949, the great American angler James E Leisering wrote The

Art of Tying the Wet Fly which was added to by his long time

fishing friend, Vernon Hidy, and released as The Art of Tying

the Wet Fly and Fishing the Flymph.

The soft hackled fly, aka the 'spider' or 'flymph' had arrived

into the modern era of fly fishing. A synopsis on the soft

hackled flies can be read in The Art of the Wet Fly

by W. S. Roger Fogg (1975).

So apart from the northern rivers of England, why do we not see

or use them? Tony Brothers is the only person I know who uses

some of the patterns in Australia. I never see them in tackle

shops, nor in fishing articles or in the fly boxes of other

anglers yet they are tremendously successful. Some fly fishermen

in England never use any other pattern, preferring to change

spider patterns depending on the time in the season, water

conditions and temperatures.

They can be a complete fly representing an emerging insect, a

drowned dun or a nymph (depending on where the fish sees it),

or an emerging caddis and they are very deadly in the hands of

an experienced 'spider' fisherman, yet they are an extremely

simple fly to tie. Is it that we anglers are always trying to

seek something very special - a fly that we can call our own

and one which, if all other fly fishers used it, would make us

famous? Is it that we simply want to experiment and create our

own patterns and enjoy their successes and failures (probably

more of the latter)? Are we not confident enough in our own

fishing ability and are led by others who we believe are better;

therefore we use or make many patterns that they use in order

to be successful? Or is it that something so simple is difficult

to believe it will catch a fish?

It is interesting to note that we do trust some of the

traditional patterns. Who would not be without a 'Red Tag'

in Tasmania; a Brown nymph on the lakes around Ballarat;

or many of the other patterns that are successful on

specific waters? So why is it that flies designed thousands

of years ago, fished extensively on rivers similar to those

in Australia, are the favourites of world class fly fishermen

and which are very deadly, are excluded from our fly boxes?

I do not have ready answers these but I can let you know how

to tie and fish them successfully. I can tell you that I am

now a convert to 'spider' fishing.

The dressing of Spider patterns is very simple. The only

two difficulties are (a) making sure that you don't use

too much body material and (b) tying soft hackles onto

the hook.

These flies are sparse and I mean very minimalist in appearance.

So you will need to conquer a few natural tendencies to

overdress the patterns. They only work well when tied correctly.

Hooks are generally very small and in sizes 16 - 18 of

normal length. You can use either light or heavy gauge

hooks. I use both as sometimes I want the fly to drift

in the surface and get this effect with a lighter hook.

You can go up in size but no bigger than a size 12. I use

these sizes when I see large duns or caddis emerging. I

believe that we use too large a hook anyway. If you want

evidence of this then you only need to cast out a size

12 dry fly on the lakes in Tasmania when duns are hatching.

You will easily see your imitation mixed in with the naturals.

If you think the hooks are small, then the body is even

smaller. In these patterns the body commences in line with

the point of the hook never longer, and the thickness of

the body is kept slim for translucency. If you want to

read about translucency on flies then you should read

J. W. Dunne's (1924) Sunshine and the Dry Fly.

There is definitely something to learn from these old masters.

The materials used can vary from just tying thread,

dubbing or feathers. The thread used must be a close

resemblance to the underside or abdomen of the insect

that you are trying to imitate. For a dun it would be

a pale yellow/green or pale brown. For a caddis it

would be more yellow. Now is the time to get out your

insect catching materials or look under rocks to determine

the right colour. They do vary between insects and waters

or even within waters. The thread is taken down to the

hook to immediately above the hook point. If you are

simply using tying thread to form the body, then you

take it back up the hook to the point where you would

tie in a hackle. In this case neat turns are required.

If the pattern calls for dubbing then the tying thread

is dubbed before it is returned to the hackle location.

Now this is the first challenge. Make the dubbing very

sparse. You must be able to see the thread through the

dubbing. If you think it is about right, then it's a

good bet that you have too much. I cannot stress enough

the need to use only a very small amount of dubbing. On

my flies (and those of the traditional patterns) a dubbed

pattern is only marginally thicker than a pattern where

tying thread has been used. Dub the material up to the

point where you will tie in a hackle. Some of the dubbing

commonly used is Hare's Ear (used in the March Brown Spider),

Mole (used in the Waterhen Bloa) & Seal's Fur. Recently I

have been using the under fur of a possum skin over a

'Greenwells' coloured thread (obtained by pulling the

thread through beeswax).

If you are to use feathers, be frugal in the amount you

use. Common feathers used for a body are Peacock, Pheasant

Tail and Heron. Recently I have also used CDC feathers

which can provide a very buoyant body.

Now for the next challenge. The key to the success of these

flies is movement. Therefore the hackles will be very soft

and longer than those used in common wet flies or dry flies.

This should give us a guide on what feathers to use.

Traditional flies used Lapwing, Plover, Dotterel (all

three now difficult or impossible to obtain) Pheasant,

Grouse, Partridge, Starling, Snipe (again difficult to

obtain), Woodcock and Waterhen. In addition there is a

frequent use of hen and game cock hackles. In earlier

times (and when some of these birds were more prolific)

the feathers were probably obtained from dead birds

located during a days fishing or individual feathers

that a live bird has lost. I have yet to discount other

types of birds, for example the breast feathers of a

'Shellback' duck, or a longish collar of possum fur.

Correct hackling of a 'spider' pattern is very sparse.

One or two turns at the most. The only variation would

be when a hen or game cock hackle is used. Feathers are

tied in at the tip end and wound around the hook. Again

I cannot stress enough the need to be frugal. If you feel

that you need to take one extra turn then it's a sure bet

you will put too much hackle onto the hook. A trick I use

is to strip one side of the feather and then wind two

turns for a game bird (e.g. Grouse or Partridge) and

three turns for a hen hackle. This works fine.

There are plenty of old books featuring soft hackled flies,

you need to read them and try a few. Typical patterns are:

Snipe and Purple, Waterhen Bloa, Orange and Partridge (these

three patterns are used predominantly by the 'die-hard'

spider fishermen of the north country), Greenwell's Spider,

Pheasant Tail, March Brown and many more. But you can

personalise these by matching the insects. I have been using

what I refer to as the 'Possum and Partridge' which is a body

of possum with a partridge hackle and 'Greenwell's' coloured

tying silk. This pattern has accounted for the 100 plus fish

I took over the 4 fishing days.

Fishing 'spider' patterns is almost as simple as the flies

themselves when explained briefly - cast across and let them

swing back downstream. But in effect it is a real skill and

once mastered and used with small sparse flies it is very

deadly. Be aware though that the fish tear these flies apart

and you will need a few of them, especially those using Partridge

or Grouse. Just as well they are a simple and quickly tied fly.

To fish these correctly you must have both the right outfit

and approach. Rods must be no shorter that 8'6" and anything

over 10' is too long. Lines should be floating and can be

either a double taper or weight forward. I prefer a weight

forward as it loads my rods faster when casting short lines.

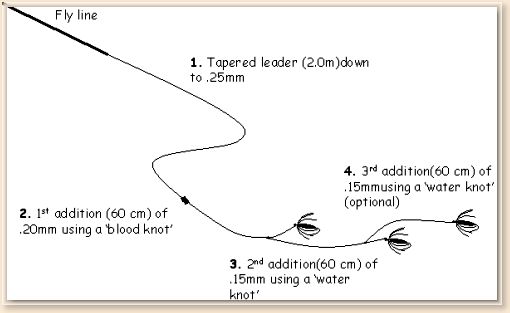

Leaders need to be a little longer than normal and be able

to hold multiple flies. I use a 10' to 12' leader with a

dropper. Some fly fishermen use three flies and I have used

both two and three flies but have not noticed any difference

between them. Anyway, two flies are enough to control.

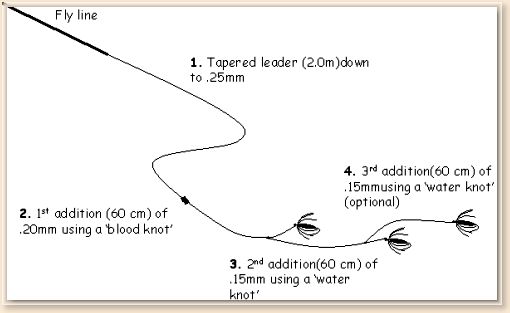

When fishing in Australia I have always made my own leaders

and still prefer to do so. The trouble here in England is

that it is difficult to get the right thickness for butts

and next two sections. So I use a 9' tapered leader with a

3lb breaking strain point from which I remove the bottom

third. I then attach a 3 foot piece of 8lb leader material

of .25mm thickness using a normal knot; in my case a blood

knot. To this I attach a further 3 foot piece of 6lb leader

material which is about .15mm thick. In other words double

strength leader materials. I attach this using a water knot

and make sure that at least a 4 - 5 inch piece of 8lb leader

protrudes from the lower side of the finished knot. Clip off

the tag on the upper side. This enables you to attach two

flies to the leader. If you want to try three flies then use

a water knot for the first section or attach another section

using the same method.

Spiders can be fished upstream or downstream. W. C. Stewart

was an advocate of the upstream approach and Leisering of

across and down but they are mainly used downstream by

modern anglers. I use them in three situations - downstream

searching or targeting specific fish, upstream to a rising

fish - and they work in all three.

Good water. The prime run is to the right of the picture.

To fish this particular stretch you would position yourself

in the middle of the stream which would allow you to cover

both sides. Four fish were taken in this stretch in one

session.

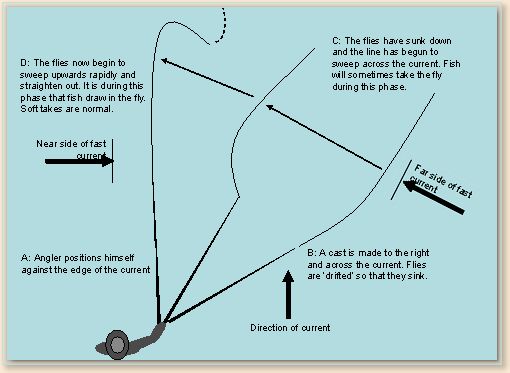

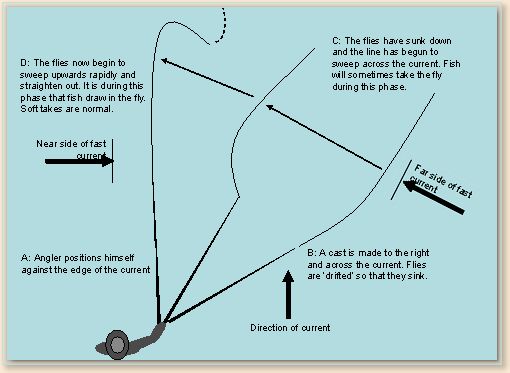

The downstream searching approach is where spiders are

deadliest. The method is easy but very specific in technique.

Only two rod lengths of fly line are required beyond the rod

tip. Any more and you begin to lose contact with the flies.

Therefore it is probable that you will be doing some deep

wading to reach the right type of water. The use of spiders

is not too effective in fast rapids. It is in its element

in the strong flows immediately upstream or downstream of

a riffle or fast water but is still effective in the slower

sections of a stream. So you need to position yourself where

the water to be fished is right up against your casting side.

Slow glide below the above fast flowing water. Spiders do

work in this type of water but I would probably leave this

and move on to faster water. An option is to drift a 'dry'

on the point down the far side and leave the 'spider' on

the dropper.

The flies are cast at a right angle from where you are standing

and directly across the current. This can be reduced to between

45° and 90° in the slower sections. It is important that you

mend line to ensure that the rod remains behind the flies.

You must keep the rod behind the flies at all times so you

need to watch the speed at which the leader travels. Do not

mend the line once the cast has been made as this will alter

the drift of the flies. You can move the rod to the opposite

side of your casting arm if you want to extend the drift.

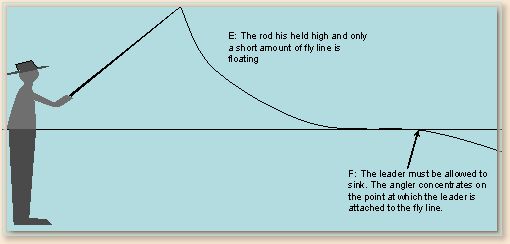

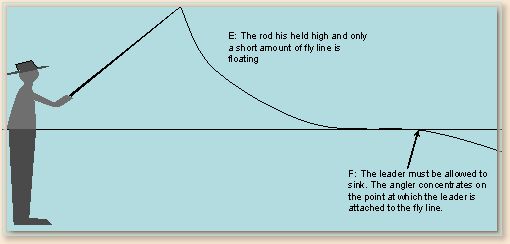

Hold the rod high. This means that the rod tip will be above

a 45° angle to your body and high enough to ensure that only

about 2' of fly line sits on the water. You should notice

that there is a very large curve in the fly line from the

tip of the rod to the water. This curve is the secret to

catching fish. The way in which the flies move in the water

means that the takes are very soft and if the rod is lower

it will result in a lot of short takes and missed fish.

Once the cast has been made, allow the flies to sink 'dead

drift' in the current. They should drift for 7 - 10 yards

before sweeping across the current. Keeping the rod high

and only having a small length on fly line on the water

helps this. As the current begins to take control, the

flies will swing across and upwards through the current

which in turn imparts movement into the fly. Exactly what

the flies are designed to do. You must be alert as a take

can occur at any point during this latter stage. Concentrate

on the point where the leader and fly line join. I keep the

fly line in my left hand right through out the cast and more

than often can feel the take before I see any change in the

leader.

If you think you feel something or observe a change in line

speed, then lift. Takes are quite varied, sometimes they are

very vigorous and right near the surface, other times it will

be a slight pull on the line. Don't strike hard. A steady lift

is all that is required and keep the rod high or you risk

losing the fish. If there is no take, then repeat the cast

and take one step forward. The step forward means you are

covering new water and will also help the flies to sink.

The other two situations still require the same technique

but differ slightly. For a fish that rises in front of you

while you are fishing downstream, then quietly approach the

position where the fish was observed and make a cast about

45° across, in front and to the far side of where the fish

moved. Where an upstream cast is required you make a cast

similar to that made with a dry fly. I also grease the line

right up to the fly in these situations.

So there you have the 'spider' patterns of northern England

and how to fish them.

Would these flies and fishing technique work down under? I

am convinced that they will. The streams that I have fished

here in England are very similar to the majority of streams

on the Australian mainland and in Tasmania. Freestone Rivers

with runs, riffles, deep pools and long flat stretches just

like the Mitta Mitta, Goulburn, Swampy Plains and the rivers

of Tasmania.

Why not try it? You might be surprised. Oh by the way! Why

not try fishing barbless? It is fast becoming the rule in

the UK, anyway it is easier to return fish and your catch

rate is not affected.

Cheers from the north and if you want to contact me my

e-mail address is philipbailey@ozemail.com.au. Or

pbailey@rcpglobal.com and my phone number is

+44 7811 286652. I might just want a fishing companion

if you are over here. ~ PB

About Philip Bailey:

Philip has a managerial and consulting background in Financial

Services for over 35 years and works globally with companies

to improve their performance.

Philip spent a short period outside of the Financial Services

Industry as owner of a small fishing tackle shop and Professional

Fishing Guide leading clients on wilderness excursions in Tasmania.

During that period Philip acted as a lobbyist on behalf of

Recreational Angling and was a key member of the task force which

established the Peak Angling body for the Australian State of

Victoria. Philip served as an inaugural board member on the

body which represented nearly a million recreational fishermen.

During this period, effective lobbying removed the devastating

effect of Scallop dredging in bays and inlets around that state.

Founder and inaugural chairman of the high profile lobby group,

The Australian Trout Foundation, Philip was one of a small band

who were responsible for the return of a closed season and bag

limits for the Victorian Trout Fishery.

Philip was also a key member of the advisory group to the Minister

responsible for Fishing in the Australian state of Victoria for

the establishment of a Peak Angling body representing 1 million

recreational anglers and was an inaugural board member representing

300 thousand trout anglers.

Born in Mildura on the Murray River, Philip began fishing at

the age of three and moved into fly fishing nearly 30 years

ago. An accomplished fly fisherman Philip has also been

President of the Victorian Fly Fishers Association, President

of the Council of Victorian Fly Fishing Clubs, a recipient

of the Councils award for recreational fishing and the Norm

trophy from Greenwells Fly Fishers.

Currently he is working in the United Kingdom as a Management

Consultant in the Financial Services industry.

|