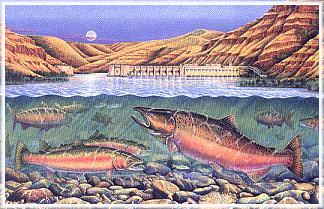

Missoula Montana-artist Monte Dolack donated "Resurrection" to Idaho Rivers

United to help raise funds to save wild salmon and steelhead. You can purchase

a signed print (24 x 32 inch) for $125.00 by contacting Liz Edrich at Idaho

Rivers United, Box 633, Boise, ID 83701, (208) 343-7481 or by

email.

When the Edwards Dam was

breached last month and a stretch of Maine's

Kennebec River flowed free for the first time in 160 years, it forever

changed the way Americans view dams. From now on, dams will no longer

be viewed as being permanent fixtures on the aquatic landscape.

Instead, they hopefully will be viewed in a more realistic light - as

industrial tools that were built to serve society's needs. Simply put,

the concrete from which they are made should no longer have to outlive

their social utility.

The Edwards Dam was removed because it blocked dwindling Atlantic salmon

runs and six other species of ocean-going fish, and because it no longer

provided enough economic benefits to justify its existence. Now that

the Kennebec has been liberated, attention has shifted to the Pacific

Northwest, where four huge dams on the lower Snake River in Washington

state have pushed the some of world's greatest anadromous fish runs to

the brink of extinction.

When Lewis and Clark made their way down the lower Snake River in 1805,

an estimated four million wild salmon and steelhead ran up into Idaho

and parts of eastern Oregon and Washington. If you had been lucky

enough to be on that expedition, you would have witnessed the greatest

runs of chinook salmon and steelhead trout the earth has ever known.

Biologists estimate that half the Columbia River's spring/summer chinook

and summer steelhead came from the Snake system. The legendary B-run

steelhead that ran up the Clearwater River in northcentral Idaho were

bigger than most coastal chinook, reaching lengths exceeding 50 inches.

The Snake River also was home to shark-sized White sturgeon. An old

black and white photo of an 18-foot sturgeon caught in the lower Snake

River hangs on my office wall.

In 1854, zoologist George Suckley wrote that the salmon were "one of the

striking wonders of the region...These fish...astonish by number and

confuse with variety." After visiting the Pacific Northwest in 1899,

biologist Richard Rathbun of the Smithsonian Institution said simply,

"the quantities of salmon which frequent these waters is beyond

calculation, and seems to be so great as to challenge human ingenuity to

affect it in any way."

Sadly, we have indeed found a way, and faster than anyone could have

possibly imagined. What has transpired on the Columbia and Snake rivers

in less than a century is perhaps the most shameful fisheries tragedy in

our nation's history. Today, less than 10,000 wild salmon and steelhead

make their way back up the Snake, and every native run of salmon and

steelhead in the Snake basin is either listed for protection under the

federal Endangered Species Act or already extinct. Coho salmon blinked

out in 1986. Only one sockeye salmon made it back to its namesake,

Redfish Lake, last year. Snake River salmon have become the buffalo of

our time.

We humans have done a lot of things to destroy these magnificent

fisheries. The first big hit came from overfishing on the lower Columbia

River beginning in the 1870s. By the late 1930s, Columbia River salmon

and steelhead runs that once numbered 10-16 million fish had already

plummeted by at least 70 percent. As waves of white settlers poured

into the Northwest, miners scoured river bottoms in search of gold,

old-growth forests that for centuries had provided salmon with shade and

cover were leveled, and unregulated livestock grazing resulted in

denuded streambanks that bled silt onto spawning beds.

Just as overfishing was starting to come under control, hydroelectric

dams began sprouting up all over the Northwest like mushrooms after a

rainstorm. Before anyone knew it, over 400 dams choked the Northwest's

rivers, decimating its anadromous fish runs.

The Snake River's wild salmon and steelhead runs hung on longer than

most because their historical spawning and rearing habitat was located

in the rugged, mountainous core of central Idaho - in today's

Selway-Bitterroot and Frank Church-River of No Return wilderness areas.

Miraculously, over 100,000 wild salmon and steelhead still returned to

spawn in the Snake, Salmon and Clearwater rivers in the early 1960s.

But that all changed when the US Army Corps of Engineers built four

highly-controversial dams on the lower Snake River between 1962-1975.

Those dams are Ice Harbor, Little Goose, Lower Monumental and Lower

Granite. The lower Snake River dams drowned over 140 miles of mainstem

spawning habitat under reservoirs and raised to eight the number of big

dams that Idaho's ocean-going fish had to cross. Since the dams were

completed, wild salmon and steelhead runs on the Snake River have

crashed by 90 percent.

Dams take the biggest toll on ocean-bound smolts that must pass through

eight dams (four on the lower Snake, and four on the lower Columbia)

that block their historical migration corridor to the sea. Scientists

estimate that over 80 percent of salmon and steelhead smolts are killed

while passing through the dams' turbines and warm, predator-filled

reservoirs. Despite the presence of fish ladders at the dams, 40

percent of the returning adult salmon perish in the overheated

reservoirs before they reach their spawning grounds.

For over 20 years, the Army Corps of Engineers has tried to mitigate for

the effects of the dams by removing smolts from the river and sending

them to the ocean in barges and trucks. But $3 billion later, this

program has failed to halt the decline of salmon and steelhead runs.

Taxpayers and Northwest ratepayers continue to pour between $300-700

million per year into this ridiculous program. The Corps of Engineers

says that money is being used to save salmon. Northwest fishing and

conservation groups say it is being used to save dams.

The lower Snake River dams fulfilled a century-long dream of the Pacific

Northwest Waterways Association - to create an "open" river from

Lewiston, Idaho to the Pacific Ocean, thus making the city the only

seaport in the Rocky Mountains. The navigation waterway the dams

created is now used to barge grain and wood products down river. The

new seaport was supposed to fuel an economic boom in the interior

Northwest, but to this day it has never been able to break even.

Residents of Nez Perce County, where Lewiston is located, pay a $500,000

a year property tax just to keep it afloat. The 465 mile-long

navigation waterway that now connects Lewiston to Portland, Oregon

relies almost entirely on federal taxpayer subsidies.

In addition to allowing barge navigation, the four lower Snake River

dams produce about 1,200 megawatts of electricity annually, or 4 percent

of the Northwest's electrical supply. Most of that power is produced

during the spring runoff, just when the Northwest needs it least.

Because they are "run-of-river" dams, they cannot be used for flood

control or irrigation storage. Thirteen farmers irrigate a total of

35,000 acres by pumping water from the pool behind Ice Harbor Dam. They

could continue farming if the dams were breached.

The vast majority of Northwest fisheries scientists say the only way

wild Snake River salmon and steelhead runs are likely to be restored is

if the lower Snake River dams are breached or "bypassed." This would

entail removing the earthen portion of each dam and letting the river

flow around the remaining concrete portion.

Last March, over 200 Northwest fisheries scientists wrote to President

Clinton warning that wild Snake River salmon and steelhead would likely

go extinct unless the lower Snake River dams are breached and the river

is allowed to run free. A July 1999 study funded by Trout Unlimited

concluded that Snake River spring/summer chinook will likely go extinct

by the year 2017 unless drastic actions to save them are taken soon.

The PATH group, a regional team of scientists charged with modeling

various Snake River salmon recovery options, recently concluded that

bypassing the dams would give Snake River chinook salmon a 80-99 percent

chance of recovery within 24 years. Continuing the smolt transportation

program, they found, would likely condemn them to extinction.

Sometime this fall, probably in late October or early November, the

Clinton Administration will release a draft recovery plan for Snake

River salmon and steelhead. The three options under consideration are:

1) continue the status quo (barging and trucking fish around the dams);

2) enhance the barging program, install costly techno-fixes at the dams

and take 1-3 million acre-feet of water from the upper Snake River basin

to augment river flows; or 3) bypass the lower Snake River dams. The

Clinton Administration will release a final recovery plan in the form of

a biological opinion by March 2000.

The decades-long fight to save Snake River salmon and steelhead is now

one of the top environmental issues in the nation. Over 350 groups

across the country including Trout Unlimited, American Rivers, the

National Wildlife Federation and Taxpayers for Common Sense now support

breaching the four lower Snake River dams in order to save the fish that

saved Lewis and Clark from starvation nearly 200 years ago. As anglers

who care deeply about our rivers, our native coldwater fisheries, and

the natural legacy we will leave our grandchildren, I invite you to join

this battle. ~ Scott Bosse

Publishers Note: Scott Bosse may be reached at

sbosse@idahorivers.org.

His toll-free phone number at Idaho Rivers United is (800) 574-7481. ~ DB

If you would like to comment on this or any other article please feel free to

post your views on the FAOL Bulletin Board!

|