SIGHT NYMPHING

This is among the most challenging aspects of fly fishing.

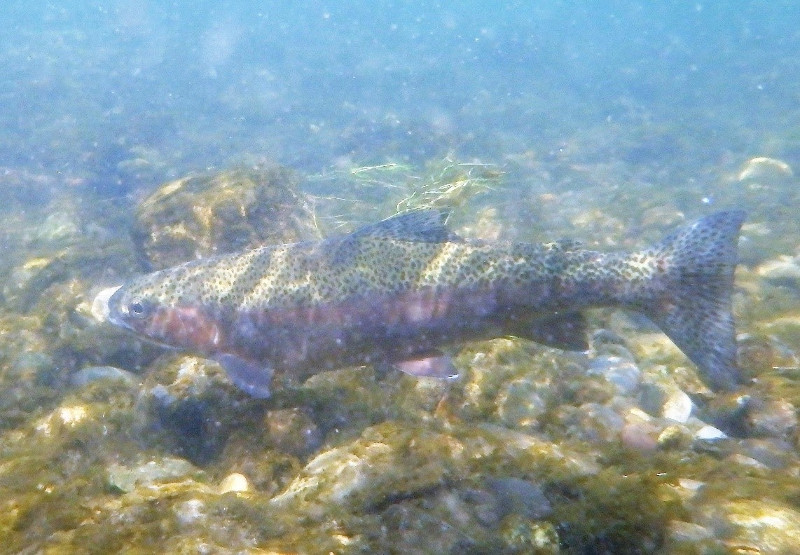

Before I begin this selection, I am going to explain what I mean by Sight Nymphing, just so we are clear on my definition and what is being discussed. Sight nymphing is accomplished by the angler being able to clearly see the trout which is going to be cast to.

The ability to actually see the trout in the water does take a bit of practice, however choosing clear water streams and rivers will make the job easier. Waters like the Spring Creeks of Paradise Valley, The Upper Yellowstone in Yellowstone National Park along with Slough Creek and Soda Butte Creek also located in the Park and Rivers like the Henry’s Fork, Silver Creek both located in Idaho along with the Upper Sections of the Big Horn River and the Missouri River below Holter Dam and even the Upper Madison in Montana are all rivers where the savvy angler can at times sight fish for Trout.

Also, there are a great many clear water small ponds and lakes where the angler can stalk the edges and sight fish with a nymph.

Sight nymphing is not a new method as a matter of fact the roots and history of the method is quite old. To my knowledge the first written observation of nymphs came from John Taverner who was in the employ of King James I and 1600 he published Certaine Experiments Concerning Fish and Fruite. He described his observations of young flies swimming backward and forwards underwater to break through the surface and take wing.

Even though the actual nymphing methods came about around the middle of the 19th century. Many of the early anglers offered some observations on the subsurface feeding of the trout. With using the words Nymphs in the explanation, it was their sense of what was going on beneath the surface which lead to the knowledge and understanding.

The first author to discuss casting to visible feeding trout was Robert Venables, who published The Experienced Angler in 1662, another edition appeared in 1676 and appeared in Isaac Walton’s selection of the Compleat Angler, 5th Edition along with the work of Walton and Charles Cotton. However due to Venables association with Oliver Cromwell the Experienced Angler was pulled from later editions of the Compleat Angler. I can only speculate that this is also the reason that most anglers ignored his observations on casting to feeding trout.

Slowly the information, observation and knowledge grew and by and bit by bit and throughout the 17th and 18th centuries anglers began to pay more attention to what the trout were feeding on beneath the surface. In 1840, John Younger published River Angling for Salmon and Trout, where he described trout feeding on flies in the middle of the water column and trout also feeding on flies nearing the surface of the water and offered suggestions on modifying patterns to imitate what the trout were feeding on during certain time periods. His work also pointed out the selectivity of the trout to certain nymphs at certain time periods of the season.

What many of the early anglers didn’t understand was that not all the mayflies or caddis the emerge all swim to the top and crawl out on the surface film, some actually emerge three to six inches beneath the surface, continue to swim to the surface and crawl out looking somewhat bedraggled and half drowned. Therefore, in many cases the wet flies of the day did in fact match part of the insects that were emerging.

Next came the ground-breaking work of William Stewart, who published in 1857 The Practical Angler, like Venables before him, he was a proponent of casting upstream in clear water to visibly feeding trout. Now Stewart also used his now famous Spiders which could be fished beneath the surface of the water, on the film and in the film, which could be interpreted as fishing emerging nymphs. Both Frederic M. Halford who would champion the dry fly and G.E.M. Skues who would become the father of modern nymphing method, noticed the work of Stewart.

G.E.M. Skues would go on to develop the methods of nymphing and because he fished on the Itchen which is a chalk stream which is very clear water where observing the trout and being able to see the trout played a major role in the development of the nymph methods. Skues work covered a period from November 1887 with a letter to the Fishing Gazette until the very end of his life in August 1949.

He is responsible for hundreds of letters and articles along with four major books in his lifetime and two more volumes published after his death.

All of his works are worth reading and carefully studying, however in my opinion his best work on nymphing was Nymph Fishing for Chalk Stream Trout, which was published in 1939. This work codified all his nymphing theories, methods and patterns.

Skues was followed by Frank Sawyer who fished the Avon River, another clear chalk stream, where the ability to see the trout and observe how they were feeding was very important in the development of his theories and methods. In 1952 he published Keeper of the Stream, which was a collection of some of his best articles and in 1958 he published Nymphs and the Trout. This volume fully explained his methods and his patterns. The most famous of his fly patterns is the Sawyer Pheasant Tail Nymph and his method of the induced take, for this method to work the angler must be able to see the trout.

The roots of sight nymphing are without a doubt a development that occurred in Great Britain and many authors of that country have since added much to our understanding of the underwater food forms and the ways the trout feed upon them.

During the early part of the 20th century American anglers were making strides and fishing nymph, yet at this time few were working on sight nymphing, many believed that much of the water in America did not lend itself to the methods of Skues and Sawyer. Yet not all, believe this to be true, one such angler was James Leisenring of Pennsylvania. Leisenring conducted much of his experiments and observations on the clear waters of the Brodhead and surrounding spring creek waters developing his methods and patterns which he referred to as “wingless wet flies”, the idea being that this pattern would imitate nymphs swimming towards the surface to hatch. His work on this produced The Art of Tying the Wet Fly, which was published in 1941 and was promptly lost in the fog of World War II.

As we set here today and examine the events of the past and discuss the important of certain volume and the contributions of various authors, I believe we often lose perspective on the progress of events. Due to certain advances in Fly Tackle, nymphing is more popular today than ever before, however in the 1950’s to 1970’s it was not unusual to encounter fly anglers who didn’t nymph, or who knew little about nymphing.

As time progressed and the works of many authors such as Doug Swisher, Carl Richards, Ernest Schwiebert, Dave Whitlock, Gary La Fontaine, Gary Borger, John Mingo and Rene Harrop to name a few offered views on the effectiveness of sight fishing nymphs.

All of the angling authors all advise to carefully approach the trout, to move in as close as practical to observe the trout and understand what the trout were actually feeding on and then to properly present the proper nymph at the proper place in the water column to entice the trout to take the offering.

Considering a Different Point of View:

During the past one hundred and fifty years we have learned a great deal about the trout and the subsurface food forms they feed on, the advances in fly tackle has been astounding and the advances in science has been remarkable.

However, with all this improvement we also may have led ourselves astray, believing things which may have little actual bearing on the feeding behavior of the trout.

The trout’s feeding behavior is instinctual and can best be describes by the fact the trout feed when they are hungry and when nature provides a bounty for the trout to pursue. Yet we have written massive number of pages in our attempts to explain the trout’s feeding behavior without really understanding everything that the trout is doing. Furthermore, we try to organize the trout’s behavior into hard and fast rules, and we often explain their actions based on our ability to think and form conscious thought.

When you study the science of the trout, you realize that the trout itself is incapable of thought and its actions are instinctual or a reaction to the conditions presented to the trout in its natural world.

The next issue is the matter of the trout’s vision, since the earliest time the angler has sought a clearer understanding of the trout’s visions and how that vision effects their feeding behavior. In 1911, Dr. Francis Ward published Marvels of Fish Life, As Revealed by the Camera, this volume began a more scientific endeavor to discover and understand the vision of the trout and the book was well received and carefully studied. He followed up with a second volume in 1920 with the publication of Animal Life Under Water again the book was well received and since that time the eye of the of the trout has been studied, dissected and written about to the degree that we all understand that the trout has remarkable vision.

All this has led to other theories and diagrams which explains the trout’s vision and supposedly how these creatures actually view their habitat and these theories have led to other speculations on the trout’s cone of vision, translucency, light patterns and many other theories.

However, I offer this, despite all of the abilities of the trout’s eye we must ask ourselves what the brain does with the images reflected to it from the eye. Remember that since the earliest days of fly fishing the angler has been able to wrap feathers and furs on hooks and deceive the trout into eating these creations.

Now, if the trout has such wonderful vision how does it fail to see the hook? Now let us consider the leader and tippet used down through the pages of history, all of them worked, yet much in recent year has written on the leaders and tippet and the limpness or stiffness of them and how the trout are put off by shiny materials.

However, in all reality, if the presentation is proper and the tippet doesn’t make the imitation do something unnatural, then the modern tippets make little difference.

The failures may be attributed to presentation being made at the wrong angle, I suspect that the angle of the presentation depending on the situation encountered may be extremely important. Another important point to consider is the angler familiarity with the food forms and how they move throughout their habitat and throughout their life cycle. Often the failure can be attributed to improper presentations, as we often present our imitations of the living food forms that the trout eat as if they are dead sticks.

Therefore, the keys to successful sight nymphing are as follows. Assuming you have mastered the skills need to cast and presentation methods to present your imitation to the trout. Then you need to learn about the food forms that the trout feeds on beneath the surface. Then you need to move slowly and quietly in the water and learn to spot the trout and move as close as possible and really observe what the trout are doing and where in the water column they are feeding. I have spent a life-time fly fishing for trout and the times that I have learned the most has not been when I have been actually fishing, but when I have curbed my desire to cast and simply observed the trout and the food forms in action so to speak.

I have watched many impatient anglers suffer frustration and defeat because they spent no time observing! Learning to spot trout in clear water, does require a little time and the more time you spend on the water the better you become, but practice is something that is required in any sport in which you wish to become proficient.

In closing I would also like the reader to understand that the comments made on certain accepted facts are not a reflection on any of the authors, I would not be able to make these determinations which their contributions, and it is the responsibility of all serious anglers to take the work of those who have come before us and develop new understandings and new theories and that is how the sport of fly fishing is moved forward.

Always remember that the trout are the final judges and our failure to learn from them and better understand them is our failure and not theirs.

Enjoy & Good Fishin’

Tom Travis, Montana Fly Fishing Outfitter/Guide