|

Last time we talked about natural lighting and how to

control it. Many of the same rules apply to artificial

lighting, but in a different way. It's still important

to control shadows and background, but the controls are

very different. With artificial light, you control the

intensity and angle of the light. You also have a little

more control over the background. However, there are some

complexities with artificial light that are difficult to

control.

First, you're going to have more difficulties getting enough

light on your subject for crisp, clear shots when you use

artificial lighting. Natural light is very intense compared

to artificial light, so partial shade isn't a serious problem

and you can control that. However, artificial light requires

direct lighting for the most part, so glare and poorly lit

parts of your subject are a problem. Having a properly lit

background is another problem.

Since artificial lighting is a requirement if you're going to

take photos of artificial flies, we first need to discuss a

few critical issues. For instance, what type of lights will

you use, how many of them are you going to use, what angle

to the fly are they going to be, etc? Believe it or not,

all these issues must be resolved before you can hope to

take quality pictures under artificial light. We'll tackle

them a couple of items at a time.

What type of camera are you using? If you're using film

(either slide or print), you need lighting balanced to that

film and sunlight. Your problems are compounded compared

to the problems you'll encounter with a digital camera.

You can't balance your camera and film to the existing

light, so you must balance your light to the film.

First, you can always use natural light from the sun. Film

is designed to work with the sun's light, so you won't encounter

a color shift from that light like you'll encounter with artificial

lights. I don't know about you, but waiting for the perfect

sunlight and finding a place to use it that's out of the wind

and weather is a real problem for me. If this is your game

though, most of your problems are over if you provide the

right reflectors in the right places to fully illuminate

the subject and background.

Since most of us will be using artificial lighting at some

time or another, and that is the subject of this article;

we need to look at the problem of color shift. Color shift

is a distortion of colors caused by a light source other

than the sun. It concerns the light spectrum and how

different types of artificial light fall into that spectrum.

If you don't know what I mean by light spectrum, look at a

rainbow sometime.

All those colors are equally balanced in natural sunlight

to create the white light that standard film was designed

to use. If your lighting source produces more of one light

frequency than the rest, the results will be a color shift

toward that color on film. God designed your eyes to naturally

balance that color shift out, but the film in your camera will

capture that shift and display it in your pictures.

Incandescent lights (normal and halogen light bulbs) produce

a color shift toward the yellow and orange side of the light

spectrum. Fluorescent lights produce a shift towards the green

end of the spectrum. The Ott light produces light closer to

natural light, but it still shifts toward the green end of

the spectrum because it is a type of fluorescent light. Just

to demonstrate the point, I took some pictures using different

types of light. The fly and the background are the same in

each picture, but the lighting changes in each picture.

In this first photo, I used a digital camera that has been

white balanced. The colors are very true to what they would

be with natural sunlight.

In this photo, I balanced the light of the camera to natural

sunlight (that is how film is balanced), but used standard

incandescent lighting like you would use to light your home.

In fact, the lights are the same as I used in the last photo,

but the camera is color balanced to the sun, not the lights.

This is the same color shift you would see on film if you used

a 35mm camera and either print or slide film.

Next, I replaced the incandescent lights with fluorescent

lights. The effects are extreme. You might note that I

didn't have enough fluorescent lights to illuminate the

fly as well as I did with the incandescent bulbs, and the

mirror I used to reflect light on the bottom of the fly

wasn't positioned well, so the contrast and glare are blown

out a bit. But, that is usually the case (most of the time)

with fluorescent lighting.

Then I used an Ott Light to illuminate the subject. I adjusted

the mirror to bounce light onto the bottom of the fly and reduce

the unbalanced lighting effect. The Ott Light is more closely

matched to sunlight than the other types of lighting, but there

is still a color shift. The folks at Ott Light were working

on a lighting system for photography, but I haven't heard if

they have perfected it yet. Still, the Ott Light produces

the best natural colors I've found for tying, even if there's

a color shift on film.

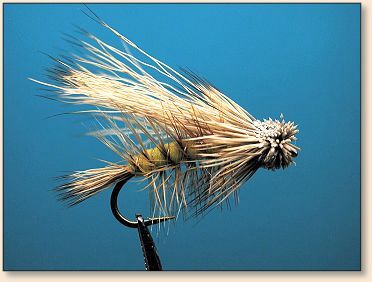

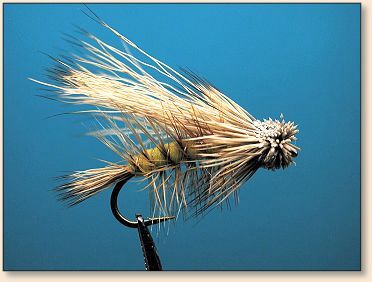

Finally, I dug back in my slides from the fly tying series I did

here on FAOL, and found a slide shot of the same type of fly taken

under photo bulbs designed to closely replicate the light waves

of the sun. (Sorry, I couldn't find the exact same fly.) The

background is the same background I used in the first photo you

saw in this article, and the lights are at the same angle. If

you notice, there is still a color shift. I've found that this

is the same type of shift I get with an elaborate flash setup

or a ring light. In the case of the ring light and flash setup,

the glare is more severe and it's hard to properly light the

background.

As you can see, the best results with film came from photo-bulb

lighting, but those types of bulbs have problems. First, they

cost a bundle and don't last very long. I pay about $6 a bulb

for photo-bulbs, and they last roughly two hours of continuous

use. Second, they are extremely hot to use. They produce more

heat than 20 of the regular bulbs, so you can't work very long

under that light. The heat isn't all that great for your camera

equipment either. Finally, they still shift the colors a little.

So far, nobody has produced an artificial lighting system that

accurately reproduces the light of the sun.

Paul Dieter wrote an article for Fly Tyer magazine a few years

ago that detailed a setup that uses a plastic dome and natural

sunlight to illuminate his photos. If you want to know more

about his system, you should either find the article, or write

him directly. He is a regular here and a nice enough guy to

give you some sound advice. Other methods to get good lighting

with natural light involve mirrors, reflectors and white,

reflective poster board. Maybe someday we can get Ronn Lucas

to disclose his setup too. Since that isn't the thrust of

this article, and natural lighting isn't very convenient for

the fly bench, I won't go any further into that subject except

to say that if you want exactly true colors on film, you need

to use natural sunlight to illuminate your subject.

Another problem with artificial lighting is light intensity and

angle, even with a digital camera. Sure, digital has the

advantage of balancing itself to the light source, but you

still need to control the intensity of the light and how it

illuminates the subject and background. This next series of

photos looks at that problem and what is required for good,

crisp photos that are pleasing to look at. Please note that

I balanced the camera's light meter to the available light

before each shot.

First, I turned off all my lights but one, and moved that one

directly overhead. As you can see, this won't work. The

camera's light meter averaged the light so that the wing

is too light and the body is too dark.

Then, I turned on two more overhead lights. The problem is

a little less severe, but it is still a problem that must be

resolved.

Next I moved the lights to the front of the fly and over the

camera. This is much better, but the bottom of the fly isn't

illuminated very well, and there is still a slight problem

with the camera averaging the light read by the light meter.

In other words, this is better, but the top is still too bright

and the bottom is still too dark.

In this photo, I turned on a light on the bottom left of the

camera and fly. As you can see, the lighting is more balanced

and the earlier problem is less severe, but the head of the fly

is still dark on the bottom.

Finally, I turned on a light to the right and below the fly

and camera. Now all the lights are turned toward the fly

and there are very few shadows. This is how I want my fly

photos to look. I am using five lights now. One is directly

above and behind the camera, one is on the upper right, one

on the upper left, one on the lower left and one on the lower

right. All the lights are angled toward the fly and also

provide even light for the background. Notice how many more

details of the fly you can see?

As you can see, good lighting and a color-balancing feature

are both important to good photos under artificial light.

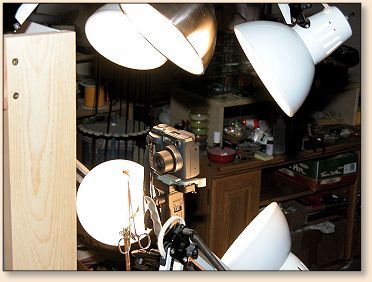

I'll end this article with a couple of shots of the setup I

use to take my indoor photos of flies. You'll probably see

that the flash I used on my camera also shifts the light a

little bit, but the color shift from blue to green on the

background is caused more by the artificial lights I'm

using than by the flash.

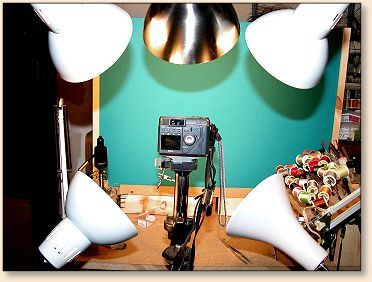

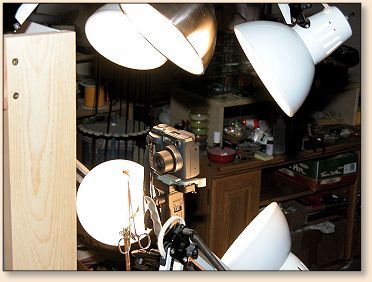

This is a front view of my lighting setup. You can see how

the five lights are pointed toward the front of the fly from

all angles to produce crisp, clear images.

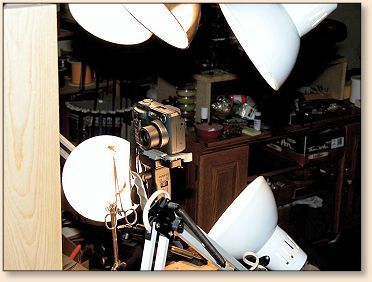

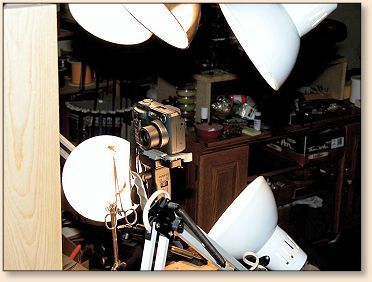

Another shot from a closer angle.

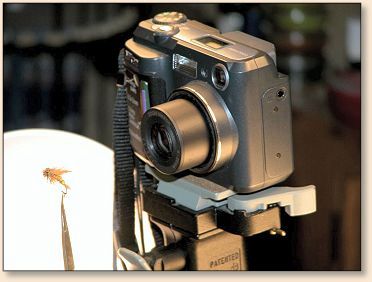

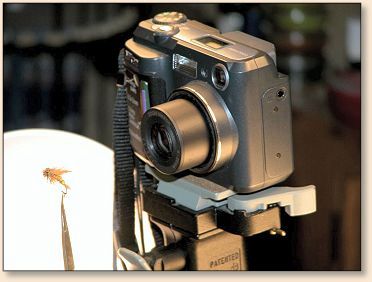

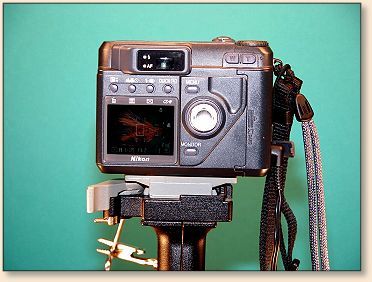

A close-up shot of the front of the camera; and its

relation to, and distance from the fly.

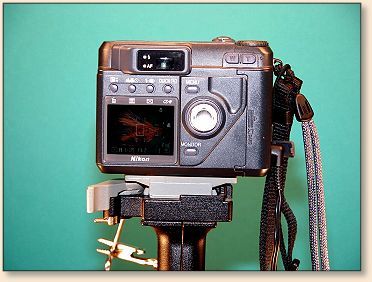

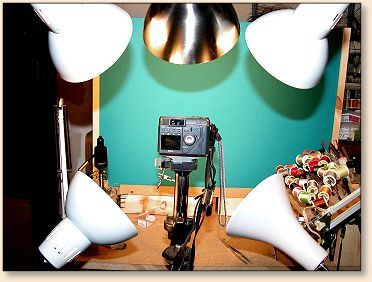

This is the view from the back of the camera. Notice

the position of the lights?

Finally, a close-up view from the back of the camera.

You can barely see the fly on the camera's screen.

That's artificial lighting in its abbreviated form. There

is a lot more to learn, but this will give you a good idea

of the requirements and problems involved with this type

of lighting. It's also a good start on the road to better

photos.

Next time we'll look at focus and how it is different with

macro photography. ~ AC

|