|

Due to popular request, I'm going to take a break from

the dull and boring stuff I write each week and do a series

of columns on close-up photography. It seems there are

number of readers who think they want to learn stuff like

fly tying and such, to include photography of tiny subjects.

It also seems that some of the same people think I know

something about that subject. I'm not really sure this

will be any less boring to you than the stuff I usually

write, but I'm willing to give it a try.

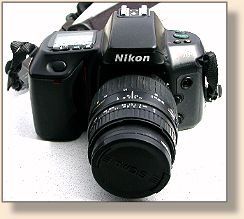

First of all, if you want to take pictures of something,

you need a camera. If you want to take pictures of

something tiny, you need a camera that works in a type

of mode called macro. That usually means either a digital

camera or one that can use interchangeable lenses (called

Single Lens Reflex (SLR)). Granted, some cameras that don't

have interchangeable lenses have a macro mode, but they

usually won't focus close enough to something as small as

an insect or artificial fly to do a lot of good. That's

why you need something that has lenses that can be changed.

I'll discuss digital cameras and their benefits/drawbacks

in a later column. Right now, I want to focus this article

on a type of camera known as a 35mm SLR camera. That's the

type of camera that's most often used in outdoor photography

and macro photography. What makes this kind of camera so

adaptable to macro photography is the fact that you can

change lenses or add accessories to your lenses that bring

tiny stuff into focus at a close range. All you need is

the camera body and some lenses adapted to the task you

have in mind.

I'll discuss digital cameras and their benefits/drawbacks

in a later column. Right now, I want to focus this article

on a type of camera known as a 35mm SLR camera. That's the

type of camera that's most often used in outdoor photography

and macro photography. What makes this kind of camera so

adaptable to macro photography is the fact that you can

change lenses or add accessories to your lenses that bring

tiny stuff into focus at a close range. All you need is

the camera body and some lenses adapted to the task you

have in mind.

The first and least expensive way to get close-up pictures

of tiny stuff is to add magnifying filters to the end of your

camera lens. These filters can be purchased in just the right

size to fit over or in the end of the camera lens you already

have on your camera. They will magnify the image your camera

sees, and allow you to focus the lens closer to your subject

than you could normally focus. Pretty easy, huh? Well, not

that easy.

Magnifying filters have several drawbacks. First, they create

an image on film that might be sharp in the center, but is almost

always fuzzy and out of focus around the edges. The additional

layers of glass cause a slight distortion of the image and

reduce the sharpness of the picture. Added lenses reduce

available light so you'll need more light and a good tripod

if you want pictures that are even slightly close to sharp.

Another problem you'll encounter is something called depth

of field. That is the space of air that's in focus in front

of your lens. As you move your camera closer or further

away from your subject, the image will come into focus and

go out of focus. That thin slice of air where the image is

in focus is called depth of field. The more you magnify

the image, especially with magnifying filters, the thinner

that depth of field becomes. Depending on the lens you're

using, and the types and numbers of filters you're using,

that slice of air can be reduced to less than a millimeter.

That means the legs on that insect or the hackle closest

to you on that fly you just tied is in focus, but the body

and everything else is fuzzy.

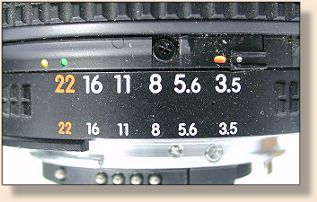

You can move farther away from your subject before you focus

the lens to increase the depth of field, but then you reduce

the size of your image and the details in the resulting photo

you want to take. You can reduce the size of the lens's

aperture (the small opening in the lens that the image

passes through) to increase the depth of field somewhat,

but that sometimes reduces the sharpness of your photograph

proportionately. By the way, reducing the size of the

aperture (setting the lens to a higher aperture (F-Stop)

number) always increases the depth of field, but on the

outside ranges of the aperture settings the image is the

least clear. The best aperture setting for clarity is

somewhere in the middle like F8 to F11, but that often

doesn't provide a usable depth of field.

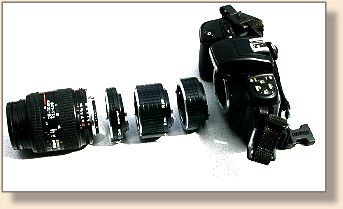

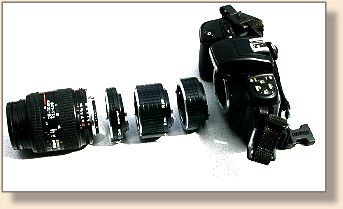

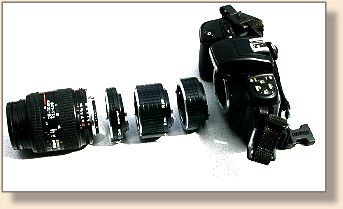

A better way to bring that image in close for photography

is to add a bellows or some extension tubes between your

camera body and the lens. That moves the aperture of the

lens further from the film, thus increasing the size of

the image; and improves the depth of field slightly over

what you get through magnifying filters. It also keeps

the image sharp all the way to the edges, unlike what

magnifying filters do to your image. The more powerful

your lens, the further from the lens the image will come

into focus, and the larger that image will be; but also,

the thinner the depth of field.

A better way to bring that image in close for photography

is to add a bellows or some extension tubes between your

camera body and the lens. That moves the aperture of the

lens further from the film, thus increasing the size of

the image; and improves the depth of field slightly over

what you get through magnifying filters. It also keeps

the image sharp all the way to the edges, unlike what

magnifying filters do to your image. The more powerful

your lens, the further from the lens the image will come

into focus, and the larger that image will be; but also,

the thinner the depth of field.

Another drawback to either of the above mentioned ways to

get close to your subject is the fact that either method

reduces the light that gets to the film, so the shutter

speeds will be slower and the need for a good tripod will

be greater. Any movement will create a fuzzy picture.

You'll need a lot of light if you want anything close

to sharp pictures.

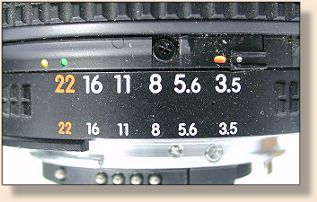

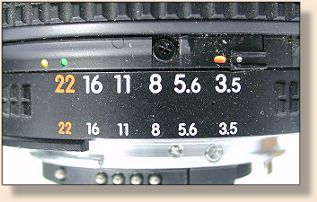

If I lost you with the word aperture, you can see what

I mean if you conduct a small experiment. Take a small

nail and punch a hole in a piece of cardboard. Then,

take another, larger nail and punch a bigger hole in

another piece of cardboard. The diameter of each hole

is the aperture that any image will pass through. Now,

place a subject in a well-lit area, grab a piece of

waxed paper or tracing paper and cover your head and

the paper with something dark. Next, place the hole

in the cardboard fairly close to your subject. Now,

move the waxed or tracing paper behind the cardboard

close enough to the hole that any image passing through

the hole will appear on the paper. You will notice that

the (inverted) image passing through the smaller hole

will be darker, but will be in focus at more variable

distances from the hole (aperture) than the image passing

through the larger hole (aperture). You will also notice

that you'll have to place the waxed paper further from the

cardboard with the small aperture to get a good focus, but

the image will be slightly larger. That is the effect of

aperture. You can see the aperture of a real lens in the

attached photograph.

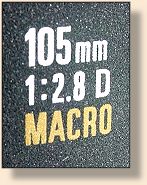

Perhaps the best way to capture a small subject on film

is to use a lens dedicated to macro photography. This

is also the most costly way to do it. Macro type lenses

offer the greatest image control and best image quality

of the three methods of taking close-up pictures. They

also pass the most light to the film and give you the best

depth of field possibilities of the three methods.

Unfortunately, they cost money, and a good macro lens

can cost a bundle. The 105mm macro lens I used for some

of my intermediate tying series photography costs roughly

$600 at most photography stores. Some lenses can cost a

whole lot more. I guess you get what you pay for, but

the cost isn't something to take lightly.

Another consideration you need to think about when capturing

images on film is something called grain. All types of film

are made with a substance placed on that film to capture the

image and store it for developing. The faster the film,

the less light you need, but the larger the grain of the

substance that captures the image will be. That means you

want a slow film if you want sharp pictures that don't

appear coarse or grainy. Faster film also has less color

density, so pictures taken on fast film won't have the

brilliant colors of pictures taken on slow film.

You should be aware of the fact that slide film offers

better color quality than print film. The process used

to transfer images from color print film to paper almost

always produces a color shift that, depending on the

quality and care of the machinery and person developing

the film, can lead to colors that aren't true to the item

you took the photo of. Some print labs will have a color

shift to the blue side of the light spectrum, and others

will shift towards the red side. Many labs will blow out

the hot colors like red and orange and subdue cool colors

like green. The resulting photo won't be true to the colors

and shades of the subject. This is especially true with

fast labs like one-hour shops use. If you want better

prints, plan on paying substantially more for quality

developing than the fast labs cost. Slide film doesn't

have the color shift problems that print film has; at

least, not as often.

As you look at my fly tying series, the beginner series

was photographed using a telephoto lens and extension tubes

with print film. The intermediate series is where I shifted

to a dedicated macro lens, and near the end, I started using

slide film after I purchased a slide scanner. You'll see the

difference each upgrade had on the quality of the pictures you

look at. The advanced series has been photographed using a

(good, costly) digital camera.

We'll discuss digital photography next week. See you then.

~ AC

|