I fished the Sauk for two winters and springs before I landed my first fish. It seems

that whenever fish were in the river, I found it to be out of shape or marginally fishable.

When fish were scarse, of course, the river was running clear and beautiful. This is

often the case with the Sauk.

The river is glacially fed and unpredictable. Even the smallest amount of rain can turn

the river into a pewter-colored torrent. Glacial runoff is natural to the Sauk, but massive

clearcuts are not. Reckless logging practices have denuded the hillsides which further

contributes to the unstable flows.

March and April are the best months to fish the Sauk for wild steelhead. They are also

good months for rain. Some seasons find the Sauk fishable for only a couple of days.

Fortunately the Sauk clears quickly after the rain subsides. The optimum time to be

fishing the Sauk is as it's dropping and clearing.

The Sauk and its many tributaries provide the spawning grounds for over half of the

Skagits remaining wild winter steelhead. If you can find the Sauk in shape, it's probably

not a bad idea to fish it and fish it hard. The window of opportunity is rarely a big-one.

The catch-and-release season begins March 1 and, just like the Skagit, closes April 30.

Fishing is not allowed above the Darrington Bridge during this special season. Highway

550 runs along the Sauk, providing foot access to various stretches of river. There are

three floats you can make.

But, first, a word of caution. The Sauk is NOT for the inexperienced boater.

Large exposed boulders, log jams, sweepers, braided channels and swift tumultuous flows

make the Sauk a very technical and dangerous river. I speak from experience. During the

1995 season, after countless hours of running the Sauk without incident, I got complacent

and came very close to capsizing my boat. We came out just fine in the end, but I was

pretty shaken. It was, however, a good reminder to me of just how fast the Sauk can

eat you up.

With sound boating skills and a huge amount of respect, a day spent floating and fishing

the Sauk river is as great an experience as any steelheader could hope for.

There are three public boat launches on the Sauk. All are primitive and require a little

sweat and ingenuity to successfully put in and take out a drift boat. The first is located at

the Darrington Bridge next to the mill. The next is at the confluence of the Suiattle River.

The third and last is on the west side of the river just upstream from where the South

Skagit Highway crosses the Sauk. But putting in at this launch, you can fish both the

Sauk and the Skagit on a single float. The takeout is at Faber's landing on the south

side of the Skagit River.

Any one of the three floats is just the right length for a full day's fishing. One is not

necessarily better than the next. They all have unique personalities, and fish can be

anywhere in them.

Skagit River

Of the fifteen great rivers featured in Trey Comb's book Steelhead Flyfishing,

only two are noted for winter angling. The Skagit is one.

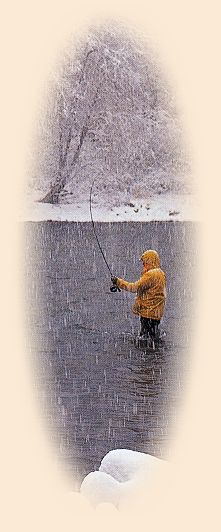

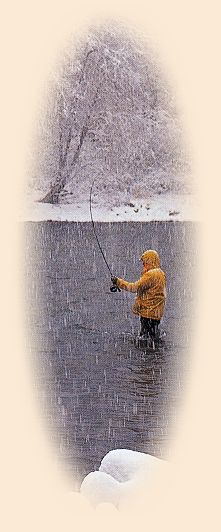

Few winter steelhead rivers have the necessary ingredients to be popular with fly fishers.

First, Northwest rivers in winter are not the most comfortable places to cast a fly - rain,

snow, sleet, hail, high water, and, sometimes extreme low water caused by sub-freezing

temperatures are everyday occurrences. Second, near-freezing water means inactive fish.

Steelhead are difficult enough to hook under optimum conditions let alone when rivers are

running in the mid-to-low thirties. So, why would the Skagit be any different? Well, it isn't,

and here's where the paradox lies.

Although the fish are winter run, the season of note among fly anglers actually occurs

in the spring. In fact most locals refer to these fish as spring run. Often you will hear

them called late returning winter runs. But they're not late at all, they come in when they

do and that happens to be spring. True winter fishing is left for a handful of hardcore

locals whose sport lies in the hooking of the occasional sea-run Dolly Varden or

hatchery-reared steelhead, not to mention tying to keep the guides of their fly rods ice free.

Late in winter the first wild steelhead begin to appear. They ascend in singles or

small pods, "run" being far too generous a term. As the weeks progress, fish numbers

increase in a sporadic trickle. Never is there a giant push. By the time fish numbers

have reached their peak in mid-April, winter, for the most part, has left the river valley

and temperatures are cool yet mild. Days are longer, and a higher sun is given more

time to warm surface currents, thus rendering steelhead more active. With water

temperatures in the mid to upper forties, fly tackle methods become a joy.

A catch-and-release season that runs from March 16 to April 30 further adds to

the pleasures. The C&R section includes the Skagit River from the Dalles Bridge

in Concrete upstream to the mouth of Bacon Creek (approximately 25 miles, not

counting braided channels) and the Sauk River from its mouth upstream to

Darrington (approximately 16 miles).

Lying within this 40-plus miles of river is some of the best steelhead fly water anywhere.

Long shallow runs that sweep over rocky bottoms, always with deep water refuge

close by, scream steelhead.

Anglers are drawn to these waters every year in search of what are perhaps the

most beautiful and powerfully built steelhead in the world. It is estimated that half

the run spends three or more years at sea, making for a fish that weighs from 10

to 15 pounds. Many reach the magic 20 pound mark with a few stretching beyond

that. Big or small, plentiful or scarce, these are "wild" steelhead (not hatchery

mutants) inhabiting the confines of this vast watershed and that is what really

makes them special.

Geography of the Watershed

The Skagit is one of the nation's great rivers. After the Columbia (including the Snake)

and Sacramento rivers, the Skagit is the third largest river system on the west coast

of the contiguous United States. The river and its many tributaries are the focus of

life and energy for more than 1.7 million acres in the North Cascades - one of the

most rugged and scenic mountain ranges in North America. And astonishing 387

glaciers (the most in any watershed in the lower 48 states) help feed more than

2,900 streams that tumble down from a sea of mountains into the Skagit River.

The Skagit is the largest watershed in the Puget Sound Basin, and provides over

20 percent of the water flowing into the sound.

The Skagit is one of the nation's great rivers. After the Columbia (including the Snake)

and Sacramento rivers, the Skagit is the third largest river system on the west coast

of the contiguous United States. The river and its many tributaries are the focus of

life and energy for more than 1.7 million acres in the North Cascades - one of the

most rugged and scenic mountain ranges in North America. And astonishing 387

glaciers (the most in any watershed in the lower 48 states) help feed more than

2,900 streams that tumble down from a sea of mountains into the Skagit River.

The Skagit is the largest watershed in the Puget Sound Basin, and provides over

20 percent of the water flowing into the sound.

The 125-mile-long centerpiece to a 13,000-year-old ecosystem begins its journey

seaward high atop the mountains of Manning Provincial Park in British Columbia.

From its headwaters, the river meanders southwest through the North Cascades,

dissecting mountains and land forms composed of rock ranging from Paleozoic

to Teratiry in age. It then turns southeast for seven miles to the U.S. border.

From there, the Skagit flows south for twenty miles in Washington. Then it heads

west, breaking through the crest of the North Cascades on its way to Puget Sound.

The combined streams of the Sauk and Suiattle rivers form the Skagits' largest

tributary. The Sauk joins the Skagit at the town of Rockport. The Sauk Basin

covers 732 square miles, making it the largest subarea of the Skagit watershed.

[For a MAP of Skagit-Sauk region, click

here.]

As the Skagit nears Puget Sound, it slows and meanders for several miles across

a huge floodplain. Eight miles from the sound, the river branches into north and

south forks, then widens to form an extensive delta. At the delta, the Skagit

discharges 10 million tons of eroded mountain (sediment) per year.

Whidbey and the San Juan Islands protect the delta from the force of storms

that travel through the Strait of Juan de Fuca. New wetlands are created as the

delta continues to grow and advance as it has over 10,000 years. Pioneer grasses

provide shelter and habitat for many species of plants and wildlife, including

immense concentrations of migrating waterfowl.

Early Angling

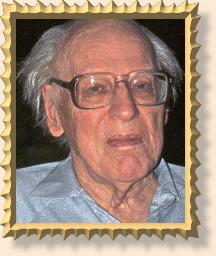

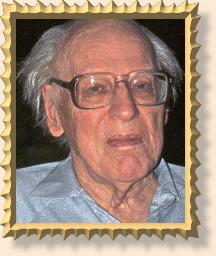

Ralph Wahl of Bellingham, Washington, may have been the first man to cast a fly

for Skagit River winter-run steelhead. "There may have been others, but they

weren't where I was fishing," Ralph says.

Ralph Wahl of Bellingham, Washington, may have been the first man to cast a fly

for Skagit River winter-run steelhead. "There may have been others, but they

weren't where I was fishing," Ralph says.

Ralph was fishing for summer-run steelhead on the North Fork Stillaguamish

whenever he could find time to break away from working at the family store

(Wahl's Department Store) in Bellingham. Ralph had been an obsessed

fisherman all of his life. When the run of Deer Creek natives would begin to

stack up in clear Stillaguamish pools below the town of Oso, so would Ralph

and a host of other dedicated steelhead anglers. Many of them would become

life-long friends and, unbeknownst to them at the time, steelhead fishing legends.

Field and Stream magazine held a monthly "big fish" contest that

ran May through December. Ralph was attentive to the fact that the rainbow

category (steelhead were counted as rainbows) during the month of December

was repeatedly dominated with entries from California's Eel River. These were

large winter-run steelhead. But more important to Ralph was that they were all

caught on fly tackle.

Ralph was intrigued with these fly-caught giants as he knew that the Skagit River,

which was practically in his backyard, hosted runs of its own winter goliaths. "If I

could figure out how to catch them, the Skagit would show those Eel boys a thing

or two about big steelhead!" In 1935 Ralph Wahl set out to do what no one had

ever done.

With persistence and unrivaled tenacity, Ralph began a blind exploration of an

unknown, untapped winter fly fishery on the Skagit River. After four years of

trials and tribulations on a bitter cold and often turbid river, Ralph had succeeded

in his quest. One cold winter's day in 1939, Ralph beached a mint-bright buck

of 17 pounds, a fish nearly twice the size of the North Fork's summer cousins.

There was no stopping Ralph now, but there was still much work to be done.

"So little was known about the 'how' of this fishing, we had to start from scratch

and dig it out for ourselves. It took a bit of doing to learn the moods of the big

swift-flowing Skagit and to find suitable holding water within casting distance of

shore (Ralph wore hip boots). It took time to get used to the below freezing

temperatures and 32-degree water.

The matter of suitable fly patterns had to be worked out. We labored over knots

to use on a brand-new material called nylon. Fast sinking lines, as we know them

today, were not to be had. Strong hooks were hard to come by - make do was

the order of the day."

It was a frigid winter day in 1947, and a foot of crusty snow covered the land at

the mouth of Gulligan Creek just east of Sedro-Woolley. The run had two parts.

Al [Knudson] favored the lower gut because this is where he caught most of his fish.

After finishing this lower sweet spot, he would fish the upper, less appealing riffle

section before leaving. Being the gracious host, he advised Wes [Drain] to take

the lower section. But Wes had ideas of his own and was drawn to the upper riffle.

Al was unsuccessful fishing his honey hole when he heard shouts from above. Wes

was fast to a huge cartwheeling steelhead. After a lengthy and tenacious struggle, a

mammoth buck that tipped the scales at 20 pounds, 7 ounces lay in the snow at Wes's

feet. The fly that soon came to be known as Drain's 20 had enticed the fish that

would stand as the unofficial state record for fly caught steelhead for twenty years.

It was Ralph Wahl who eventually took top honors with a fish that bested Wes's

by one ounce.

Fishing

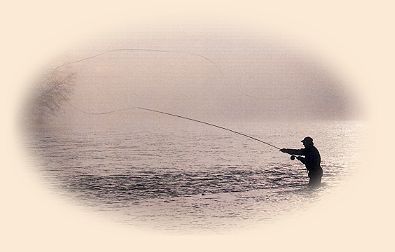

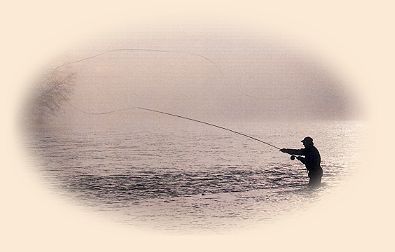

The Skagit is classic big water with a lot of places for steelhead to hide - many of

them not within the reach of a fly. In fact, most of the holding lies are better suited

to other methods of angling. When viewing the river from a nearby hillside, I still

find it hard to believe that we ever take fish on flies in the Skagit.

Fortunately, many of the steelhead that travel up the Skagit do so close to shore and

out of the main flow of the current. This "path of least resistance" is what to look for

when seeking suitable fly water. In effect, we are fishing for traveling steelhead. The

best places to fish are those that force the steelhead to slow down or stop; a fast

shallow riffle that slows and deepens, the tailout above a long fast stretch or heavy

rapid, the first deep slot above an expanse of shallow nondescript water, etc.

If the river bottom is made up of good-sized rocks and boulders, it usually makes

for a more attractive holding lie, but big rock is not entirely necessary to hold a

traveling steelhead. As long as the bottom is hard (not sand or silt) with cover in

the form of depth or a choppy surface, it's worth a look. Remember that the

operative word is "traveling". Therefore, a pool or piece of water that is void

of fish one hour may hold one or more the next.

Where water depth is concerned, two feet is not too shallow and eight feet is not

too deep, three to six being about perfect. Where many people cheat themselves

of a possible fish (maybe the only one in a day's efforts) is in the two to four foot

range. Skagit fish will hold in surprisingly shallow water. Remember, if the water

is two-feet deep with enough flow to swing a fly, it has potential.

Almost everybody fishes a farily large fly with a lot of built-in action such as Bob

Aid and John Farrar's marabous, Spey flies of varying degrees of fullness, and

endless variations of the General Practitioner. Black, orange, and purple get top

billing as the most popular colors. And Alec Jackson's Spey hooks wear them

well. [For a FLIES of Skagit-Sauk region, click

here.]

I like to think of Skagit country as the land of freestyle fly tying where people cut

loose from their inhibitions at the tying bench and just let it roll - whever happens,

happens. With the massive ocean like the Pacific, an immense river system like

the Skagit, and a mysterious sea-going fish that returns to rivers not for good but

for spawn, one can't help but let the imagination run wild when tying flies.

Even a small steelhead is a big fish when caught on fly tackle. If steelhead never

grew beyond eight pounds, it is doubtful they would be any less important as a

gamefish. Wild-eyed hopefuls would still spend lots of dollars on tackle and

equipment and would still travel, sometimes great distances, to use it. The writers

would still write, the tiers would still tie, and fly reels would still need to hold at

least 150 yards of backing. ~ Dec Hogan

For a MAP of the Skagit-Sauk, click

here.

For the FLIES for Skagit-Sauk, click

here.

To ORDER Skagit-Sauk direct from the publisher, click

HERE.

Credits: From Skagit-Sauk part of the Steelhead River

Journal series, published by Frank Amato Publications.

We greatly appreciate use permission.

|

The Skagit is one of the nation's great rivers. After the Columbia (including the Snake)

and Sacramento rivers, the Skagit is the third largest river system on the west coast

of the contiguous United States. The river and its many tributaries are the focus of

life and energy for more than 1.7 million acres in the North Cascades - one of the

most rugged and scenic mountain ranges in North America. And astonishing 387

glaciers (the most in any watershed in the lower 48 states) help feed more than

2,900 streams that tumble down from a sea of mountains into the Skagit River.

The Skagit is the largest watershed in the Puget Sound Basin, and provides over

20 percent of the water flowing into the sound.

The Skagit is one of the nation's great rivers. After the Columbia (including the Snake)

and Sacramento rivers, the Skagit is the third largest river system on the west coast

of the contiguous United States. The river and its many tributaries are the focus of

life and energy for more than 1.7 million acres in the North Cascades - one of the

most rugged and scenic mountain ranges in North America. And astonishing 387

glaciers (the most in any watershed in the lower 48 states) help feed more than

2,900 streams that tumble down from a sea of mountains into the Skagit River.

The Skagit is the largest watershed in the Puget Sound Basin, and provides over

20 percent of the water flowing into the sound. Ralph Wahl of Bellingham, Washington, may have been the first man to cast a fly

for Skagit River winter-run steelhead. "There may have been others, but they

weren't where I was fishing," Ralph says.

Ralph Wahl of Bellingham, Washington, may have been the first man to cast a fly

for Skagit River winter-run steelhead. "There may have been others, but they

weren't where I was fishing," Ralph says.