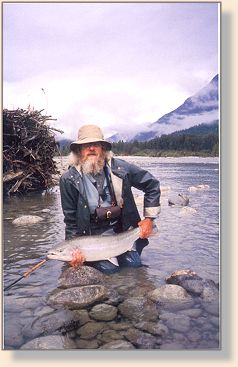

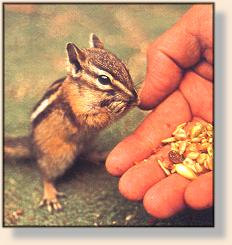

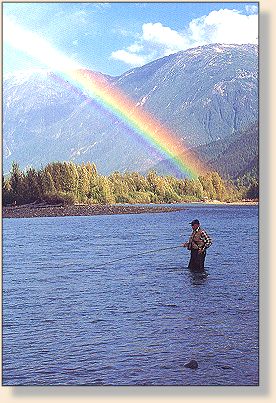

My memories: personal experiences with fish caught, wild animals,

spectatular scenery and people fished with - these are some that come to

mind when I think of the Dean. Some memories are there for the moment,

some last for days and others for a life-time. My most memorable, though,

occured in 1990 when I took my 12-year-old son to the Dean.

We had fished for two days with not much doing and it was getting late in

the day, so Charles and I decided to call it a day and return to camp. On

the raft trip across the river, C.T. changed his mind and decided he wanted

to fish more.

I stood beside him instructing him that the proper way to fly-fish a pool

for steelhead is to make a cast, then walk downstream a couple of paces,

cast again and continue this procedure until the piece of water has been

covered. We had made our first move and his third cast when his fly

stopped and he was astounded when the "bottom" moved.

Some fish are never meant to be landed and this was one of them, partly

because of Charles' inexperience with fly equipment when river fishing.

In this case, the fish virtually played the boy. Charles found he had a

very active bundle of energy at the end of his line. In no time the fish

had all the line out and most of the backing. With a logjam below us

and no room to follow the fish from our side of the river, we took the

raft over to the other side and played the fish from the long shingle bank.

Even then, the fish managed to play the boy to the end of the Camp Pool and

I had to show Charles how to walk a fish back upstream by pointing the

rod straight to the fish, holding the reel so no line can come off and

walking upstream maintaining steady pressure. It worked and by the

time Charles landed his fish, 45 minutes had lapsed. He was one proud

lad as he released his six-pound steelhead back into the Dean. That fish

was his first steelhead, first fly-caught, first caught on a fly he had tied,

first summer-run and first Dean River steelhead.

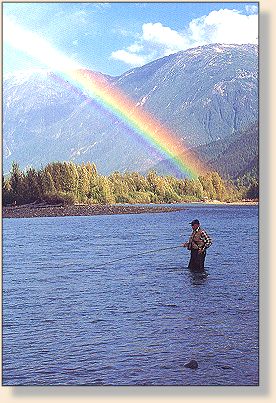

Full of adventure around every corner, the Dean indeed provides memories

to whose who visit her. Over the past 17 seasons she has provided me much

enjoyment and things to reflect. In Norse mythology Valhalla was the place

where Odin received the souls of heros slain in battle. Some steelhead

fly-fishing aficionados believe that the Dean is where all dedicated practitioners

are received by the god of steelhead fly fishing.

The History, the River and Early Sportfishing

It is because of the Dean's magnificent summer-run steelhead fly fishing,

combined with the wilderness setting that the city-bred anglers long for,

that we refer to it as our Valhalla. [See map,

click here.]

However, the river's remoteness that attracts us now was just a matter

of fate. During the early exploration of the North American continent it

was rumoured that there was a sea route through the continent below

the polar ice cap and it was given the name "the Strait of Anion." During

the latter part of the 18th and early part of the 19th centuries, until it was

proven that the Strait of Anion did not exist, European ships explored the

west coast of British Columbia looking for the mythical passage.

Captain George Vancourver explored the Dean Channel in June of 1763 and

named the inlet after Dean King of Raphoe, Ireland. While Vancouver

was exploring the coast by ship, another explorer, a Scot by the name of

Alexander McKenzie, was searching for a land route across the continent

using inland waterways. One month following Vancouver's departure from

the area, McKensie tasted the salt water of North Bentinck arm.

In 1876, the Canadian Pacific Railway surveys and engineers returned

to the Dean and explored further its suitability was the western

terminus for the transcontinental. Because of political reasons, the northern

routes [railroad] through the mountians were abandoned by the CPR

[Canadian Pacific Railway] when the Canadian government adopted

the Burrard Inlet route in 1879. . . . The Dean remained undiscovered

by sportsman, and apart from the activities of small logging operations,

trappers and prospectors, the Dean remained the domain of the Kimsquit

people until the 1950s.

The River

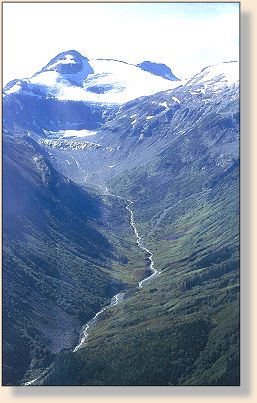

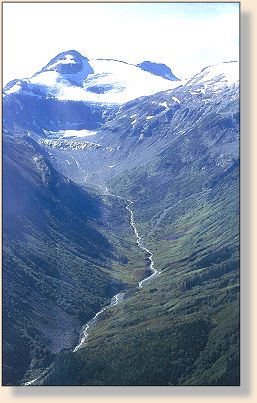

The Dean River originates in Chilcotin Plateau and meanders through

the interior high-altitude forest and grasslands picking up nutrients from

the soils and eventually cascading its way through the eastern part of the

Coast Mountains to the sea. Anyone flying over the Coast Mountains

cannot help but notice the sea of white, even in the middle of summer.

The cap of the range is also all glacial and, as the Dean passes through it,

many of the tributaries add glacial tint to the river. The degree of tint has

profound effects on the selection of fly-fishing technique and will be

discussed at length later.

The Dean River originates in Chilcotin Plateau and meanders through

the interior high-altitude forest and grasslands picking up nutrients from

the soils and eventually cascading its way through the eastern part of the

Coast Mountains to the sea. Anyone flying over the Coast Mountains

cannot help but notice the sea of white, even in the middle of summer.

The cap of the range is also all glacial and, as the Dean passes through it,

many of the tributaries add glacial tint to the river. The degree of tint has

profound effects on the selection of fly-fishing technique and will be

discussed at length later.

Above the natural anadromous barrier - a 60-foot-high falls - located a mile

or so above the the junction with the Iltasyuko River, the Dean watershed

is primarily the domain of rainbow trout. Because the nature of the

Chilcotin Plateau soils, the water is richer in dissolved minerals than it is

in coastal steelhead streams. The nutrient-rich water produces larger

quantities of insects resulting in streams with good trout populations.

However, another characteristic of the Chilcotin Plateau is its climate:

long, extremely cold winter and relatively short but hot summers. So,

although the streams are rich in insects, the growing season is short and

trout, although plentiful, take a number of years to become large. While

the fly fishing in such places as the Upper Dean, Anahim Lake and Nimpo

Lake, has attracted anglers for years it does not form part of this treatise.

The focus instead is on the lower Dean's world-class summer-run steelhead

fly fishing that is sampled by anglers journeying far and wide to her banks.

Native accounts had, for a number of years, led to rumours that the Dean

supported a large population of steelhead. Confirmation of these fish came

fromn the large by-catch of summer-runs by commercial gillnetters operating

in Burke and Dean channels. By the mid - to late 1950's, the Dean River

had begun to draw interest from sportfishers.

Native accounts had, for a number of years, led to rumours that the Dean

supported a large population of steelhead. Confirmation of these fish came

fromn the large by-catch of summer-runs by commercial gillnetters operating

in Burke and Dean channels. By the mid - to late 1950's, the Dean River

had begun to draw interest from sportfishers.

The first rod-caught steelhead were taken from Tanya Lake during pack-horse

trips into the Rainbow Mountains by Bella Coola guide Tommy Walker in

the mid-1940s. However, it was to be the summer-run steelhead migration through

the Lower Dean above the canyon that would bring the river's fly-fishing

world-wide attention.

Since time immemorial the Kimsquit people had poled their canoes to pools

above the Dean's canyon to catch steelhead using traditional native fishing

techniques. It was not until Al Else settled in the Bella Coola valley, and

learned through conversations with natives or logging crew that steelhead

could be netted in pools above the canyon, that the sport potential of the

Lower Dean was considered to be worth exploring.

Access to the Dean in those early years was by the Indian trail over

the canyon and in the early 1960s by float plane. Because of the

Dean's remotenss and the difficult access, it was visited by few

anglers. [Dan] Blewett had to pack of lot of the equipment for

his guiding operation over the Indian trial, and he bulldozed a trail

over the canyon ridge to haul his first boat and motor in. In 1961,

however, logging started in earnest below the canyon and in the winter

of 1963 and spring of 1964, Mayo Logging extended the road above the

canyon, reaching the vicinity of Blewett's camp. These large-scale logging

operating together with the construction of an airstrip at the tidewater had

two effects on the Dean and its steelhead. Access was opened up, which

made it easier for Blewett to get supplies and equipment to his camp; but

non-guided anglers now had access to the camp.

Through the 1960's and '70s more anglers came as word spread of the good

fly fishing; but in the mid-1980s angling pressure exploded when the Dean

experienced phenomenal runs of steelhead. The Dean became the

"destination" river.

The Fish

The Dean's Summer-Run Steelhead

Steelhead stocks are specific to certain rivers, and stocks enter those rivers

when water conditions provide ready access to the habitat where the fish were

hatched. In some rivers these conditions occur in the winter and spring and

coincide with the fishes' sexual maturity. Thus, steelhead are divided into two

classes - winter-run and summer-run. In the Dean River, optimum water

conditions occur in the summer and fall months; thus, the Dean river steelhead

is a summer-run fish. In all likelihood there is a run in the spring which spawns

below the canyon, but the the river's closed season from October 1 to May

31 there are no anglers to test the waters.

For a river to host summer-run steelhead, there must be obstacles that block

migration during the spawning run. Because the Dean River valley's climate

resembles that of the Chilcotin Plateau, winter comes early and lasts long, and

the river becomes filled with devil's ice and in some places freezes over. Dean

River steelhead enter during the summer months - June through September -

when the high-velocity, turbulent water in the Dean Canyon is warmer, the upper

river is free from ice and the fish are in their physical prime and are not encumbered

with sexual maturity. Steelhead full of roe or milt are poor atheletes.

Once steelhead get into a river system such as the Dean that has winter icing, the

fish find deep slow pools; or in the case of the Dean's tributary the Takia River,

migrate to Tanya Lake and winter below the ice, dropping back to the river to

spawn in the spring. The low water temperatures found through the November

to April winter holding period slow the fishes' metabolism, helping to conserve

energy and convert the store of body fat into roe or milt. Spawning takes place

in the late spring of the year following river entry, usually in April and May.

Consequently, June fish can remain in the system 10 or 11 months before

spawning.

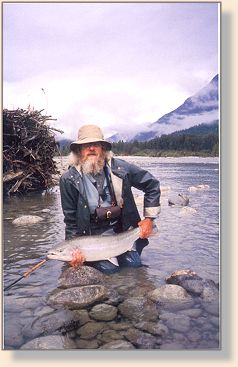

Other Salmonids

The Dean River is home to all species of Pacific salmonids, including steelhead

and cutthroat trout. The June chinook fishery below the canyon is well subscribed,

with fish in 30 to 50-pound range not uncommon. Above the canyon, chinooks are

targeted in mid-June into July but give way to steelhead as July progresses.

Nonetheless, anglers fishing through July often battle these monsters with fly

tackle. The largest I have landed after a 45-minute struggle was a fish over 30

pounds that measured 42 inch and I have had other fish in the 15-to 30-pound-range

test my tackle over the years.

The Dean River is home to all species of Pacific salmonids, including steelhead

and cutthroat trout. The June chinook fishery below the canyon is well subscribed,

with fish in 30 to 50-pound range not uncommon. Above the canyon, chinooks are

targeted in mid-June into July but give way to steelhead as July progresses.

Nonetheless, anglers fishing through July often battle these monsters with fly

tackle. The largest I have landed after a 45-minute struggle was a fish over 30

pounds that measured 42 inch and I have had other fish in the 15-to 30-pound-range

test my tackle over the years.

Sea-run cutthroat also migrate above the canyon and are a pleasant distraction,

although not plentiful. My largest was a 19-incher taken on a General Noel

Money pattern and a floating line.

In late August and September coho start to show up and often take a fly and a

few chum salmon manage to get above the canyon. However, it is the Dean's

summer-run steelhead that attracts anglers from all over the globe.

Fly Patterns

I have sampled about three dozen British Columbian steelhead streams, and the

Dean is unique. No other summer-run stream is as rich in nutrients and produces

such large numbers of fish, yet is so affected by glacial melt that it alone can

influence technique and fly-pattern selection. Therefore, glacial conditions are

inportant and the degree of siltation can change throughout the day, particularly

if there is wide daily fluctuations in temperature. But steelhead fly-fishers need to

consider all the following factors when choosing their fur and feather enticements:

- Glacial melt conditions - to what depth can you see the river bottom?

- Other water conditions - temperature, velocity and surface turbulence.

- Light conditions - is it sunny, cloudy or is the water shaded?

- Time of day - early morning, mid-day, evening.

- State of the fish - fresh-run or present in the river for some time.

- Method of presentation.

When fishing conditions deteriorate - and they do daily - the skillful, knowledgable

fly-fisher shines over those average-skilled ones. By marrying fly-fishing method to

conditions and fly selection, a competent fly-fisher often can catch fish under the

most trying conditions. The most trying Dean River conditions that I can think of

are mid-afternoon on a glassy run, baked in sunshine and a river flowing with about

five-foot visibility.

To avoid wasting time trying different types of flies, concentrate more of matching

technique with conditions and keep fly choices to a minimum. Because the

opportunity exists to try all five fly-fishing techniques you need to have a variety

of fly types to satisfy those opportunities. However, with five fly types in

different sizes you can meet most opportunities. [For the flies for The Dean River,

click here.]

Regulations

To avoid the "tragedy of the commons" so typical of public waters in North America,

through the late 1980s the Fisheries Branch with consultation produced the Angling

Guide Policy to control guiding and implemented a Classified Waters System for 42

destination waters. The Dean became a Class I river under the system in 1990:

the number of people going to the river now is controlled, as is the 40/60% split

between guided and non-guided anglers.

All anglers going to the Dean must have a classified-waters license along with the

other licenses necessary for fishing in British Columbis such as annual license,

steelhead license or, if early in the season, a salmon license. There is no

restriction on the number of days a Canadian citizin can go to the Dean, providing

the fisher has the required licenses. All non-Canadians are limited to a maximum

8-day stay once per year and must enter a draw for a time . . . At the writing of

this book the Classified Waters System is under review. [Check with a registered

guide for current regulations.] ~ Art Lingren

For a MAP of The Dean River, click here.

For the FLIES for The Dean River, click here.

To ORDER the Dean direct from the publisher, click

HERE.

Credits: From Dean part of the Steelhead River

Journal series, published by Frank Amato Publications.

We greatly appreciate use permission.

|

Native accounts had, for a number of years, led to rumours that the Dean

supported a large population of steelhead. Confirmation of these fish came

fromn the large by-catch of summer-runs by commercial gillnetters operating

in Burke and Dean channels. By the mid - to late 1950's, the Dean River

had begun to draw interest from sportfishers.

Native accounts had, for a number of years, led to rumours that the Dean

supported a large population of steelhead. Confirmation of these fish came

fromn the large by-catch of summer-runs by commercial gillnetters operating

in Burke and Dean channels. By the mid - to late 1950's, the Dean River

had begun to draw interest from sportfishers.

The Dean River is home to all species of Pacific salmonids, including steelhead

and cutthroat trout. The June chinook fishery below the canyon is well subscribed,

with fish in 30 to 50-pound range not uncommon. Above the canyon, chinooks are

targeted in mid-June into July but give way to steelhead as July progresses.

Nonetheless, anglers fishing through July often battle these monsters with fly

tackle. The largest I have landed after a 45-minute struggle was a fish over 30

pounds that measured 42 inch and I have had other fish in the 15-to 30-pound-range

test my tackle over the years.

The Dean River is home to all species of Pacific salmonids, including steelhead

and cutthroat trout. The June chinook fishery below the canyon is well subscribed,

with fish in 30 to 50-pound range not uncommon. Above the canyon, chinooks are

targeted in mid-June into July but give way to steelhead as July progresses.

Nonetheless, anglers fishing through July often battle these monsters with fly

tackle. The largest I have landed after a 45-minute struggle was a fish over 30

pounds that measured 42 inch and I have had other fish in the 15-to 30-pound-range

test my tackle over the years.